eBook - ePub

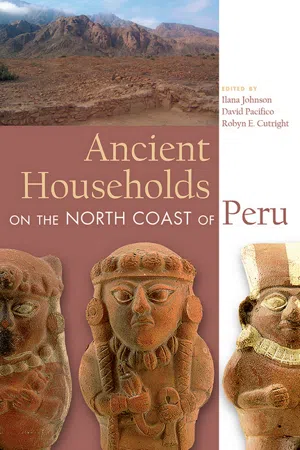

Ancient Households on the North Coast of Peru

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Households on the North Coast of Peru

About this book

Ancient Households on the North Coast of Peru provides insight into the organization of complex, urban, and state-level society in the region from a household perspective, using observations from diverse North Coast households to generate new understandings of broader social processes in and beyond Andean prehistory.

Many volumes on this region are limited to one time period or civilization, often the Moche. While Ancient Households on the North Coast of Peru does examine the Moche, it offers a wider thematic approach to a broader swath of prehistory. Chapters on various time periods use a comparable scale of analysis to examine long-term continuity and change and draw on a large corpus of prior research on states, rulership, and cosmology to offer new insight into the intersection of household, community, and state. Contributors address social reproduction, construction and reinforcement of gender identities and social hierarchy, household permanence and resilience, and expression of identity through cuisine.

This volume challenges common concepts of the "household" in archaeology by demonstrating the complexity and heterogeneity of household-level dynamics as they intersect with institutions at broader social scales and takes a comparative perspective on daily life within one region of the Andes. It will be of interest to both students and scholars of South American archaeology and household archaeology.

Contributors: Brian R. Billman, David Chicoine, Guy S. Duke, Hugo Ikehara, Giles Spence-Morrow, Jessica Ortiz, Edward Swenson, Kari A. Zobler

Many volumes on this region are limited to one time period or civilization, often the Moche. While Ancient Households on the North Coast of Peru does examine the Moche, it offers a wider thematic approach to a broader swath of prehistory. Chapters on various time periods use a comparable scale of analysis to examine long-term continuity and change and draw on a large corpus of prior research on states, rulership, and cosmology to offer new insight into the intersection of household, community, and state. Contributors address social reproduction, construction and reinforcement of gender identities and social hierarchy, household permanence and resilience, and expression of identity through cuisine.

This volume challenges common concepts of the "household" in archaeology by demonstrating the complexity and heterogeneity of household-level dynamics as they intersect with institutions at broader social scales and takes a comparative perspective on daily life within one region of the Andes. It will be of interest to both students and scholars of South American archaeology and household archaeology.

Contributors: Brian R. Billman, David Chicoine, Guy S. Duke, Hugo Ikehara, Giles Spence-Morrow, Jessica Ortiz, Edward Swenson, Kari A. Zobler

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ancient Households on the North Coast of Peru by Ilana Johnson, David Pacifico, Robyn E. Cutright, Ilana Johnson,David Pacifico,Robyn E. Cutright in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Diverse, Dynamic, and Enduring

Ancient Households on the North Coast of Peru

David Pacifico and Ilana Johnson

The enduring presence of domestic contexts in the archaeological record means that the household perspective is as valuable as ever for deciphering the cultural beliefs and practices of Peru’s ancient inhabitants. Building on a long tradition of household archaeology, this book contributes new case studies focusing on ancient households on the north coast of Peru. All of the studies in this volume build upon previous efforts in household archaeology in the Andes. Many also invoke related perspectives, including community archaeology (e.g., Canuto and Yaeger 2000) and neighborhood archaeology (e.g., Pacifico and Truex 2019b). Accordingly, the cases that follow should be considered complementary to earlier studies and parallel approaches.

Nevertheless, the findings here suggest that revision is needed to our understanding of households. Specifically, this volume emphasizes hitherto unrealized dynamism, mutability, and diversity of Precolumbian houses and households. Following a century of archaeological research focusing on the monumental and mortuary contexts of North Coast archaeological sites, this volume presents the first trans-temporal synthesis of household research in the North Coast and, in so doing, covers more than 1,000 years of coastal prehistory. The material diversity presented in this volume suggests that households take different forms within a single culture or even settlement. Households serve a variety of purposes that change over time, causing the same household to leave different archaeological indices depending on the spatial and temporal context within which the household functioned. In addition, households combine, fragment, and recombine in new configurations, which suggests that they have fluid relationships with larger-scale settlements like neighborhoods, communities, cities, and states. Fluidity does not necessarily imply weak relationships. Instead, it indicates the dynamic nature of social and political alliances on the North Coast in prehistory. The underlying factors that affect household diversity and dynamism are faced by families around the world. Population movement can be coordinated with agricultural cycles, kinship organization can be reorganized by economic changes, or local identities can be resilient or disappear in the face of culture change. We can therefore use the newly discovered household contexts presented in this book to compare ancient Andean case studies with those from other times and places. These complex nuances and their comparative promise attest to the vitality and relevance of household archaeology for exploring human culture and society in the past.

Categories of Thought

Household archaeology is the study of daily life, domestic practices, and household social organization. This archaeological approach has existed for many decades, if not centuries if we count early excavations at Pompeii (Ceram 1979). Yet there is only tacit agreement about the terms used to investigate and analyze archaeological households. In place of explicit agreement, many archaeologists hover around a set of concepts that are “good to think with.” Here we highlight four interrelated categories of thought that have provided traction in household archaeology: materiality, practice, scale, and symbolism. We highlight these categories in particular, because the cases detailed in this volume both build on the momentum of these terms but also suggest new intellectual trajectories described by these terms within household archaeology. We would also highlight that these intellectual categories implicate one another as essential dimensions for analysis, and they are likely to be difficult to disentangle. This complexity is an optimistic one, for it highlights the promise of new and rich understandings of the past from the perspective of residential life.

Materiality: House and Household

Household archaeology requires simultaneous attention to the physical remains of residential structures (viz. houses) and the material remains of the people who lived, worked, and visited with and around the structure (Ames 1996; Blanton 1994; Haviland 1985; Hirth 1993; Netting 1982; Netting et al. 1984; Wilk and Rathje 1982). An early, useful definition endures in Andean archaeology. This definition is entirely focused on materiality; it defines the household as “the smallest architectural and artifactual assemblage repeated across a settlement” subject to site formation processes during habitation, abandonment, and afterward (LaMotta and Schiffer 1999; Stanish 1989, 11). This archaeological definition focuses on the materiality both of houses themselves as well as the physical remains of people and activities that took place within them. Moreover, this definition emphasizes the fundamental nature of households to their wider social contexts. Attention to both container and contained is an essential and enduring characteristic of household archaeology (Hendon 2010).

A focus on the materiality of houses can help drive clear, local material indicators. For example, an elemental pattern based strictly on materiality is found among urban Moche houses—defined by multipurpose rooms with benches as well as access to essential areas, including storage (Bawden1977, 1978, 1982; Brennan 1982; Chapdelaine 2009; Lockard 2005, 2009; Shimada 1994). Additional architectural indices of social meaning can also be defined by focusing on the materiality of houses and households, including architecture intended to shape movement, provide privacy, impose restriction, and elaborate on design standards (Moore 1992, 1996, 2003). Floors, ramps, and wall finishes can be used to indicate household status (Attarian 2003a, 2003b; Bawden 1982; Campbell 1998; Johnson 2010; Klymyshyn 1982; Topic 1977, 1982; Van Gijseghem 2001). Residence morphology and artifact decoration can indicate household ethnicity and immigration episodes (Aldenderfer and Stanish 1993; Dillehay 2001; Johnson 2008; Kent et al. 2009; Rosas Rintel 2010; Swenson 2004; Vaughn 2005). The materiality of assemblages within houses is also meaningful. Finewares and high-value items can be considered markers for household status or ethnic identity (Bawden 1983, 1986, 1994; Gumerman and Briceño 2003; Johnson 2010; Mehaffey 1998; Rosas Rintel 2010; Stanish 1989). Plant and animal remains can signal distribution patterns, economic organization, and wealth and status of household inhabitants (Gumerman 1991; Hastorf 1991; Pozorski 1976; Pozorski and Pozorski 2003; Rosello et al. 2001; Ryser 1998; Shimada and Shimada 1981; Tate 1998; Vasquez and Rosales 2004).

At the end of the twentieth century, archaeologists began to expand and revise this earliest definition of Andean archaeological households (e.g., Janusek 2004, 2009; Nash 2009). A more recent revision of the traditional definition would direct our attention away from a single fundamental pattern and toward the potential diversity of households within a single settlement (Bawden 1982; Pacifico 2014; Shimada 1994; Uceda Castillo and Morales 2002, 2003, 2005, 2006; Uceda Castillo et al. 1997, 1998, 2004; Vogel 2003, 2012). Certainly, this approach complicates archaeological research, but it also promises to reveal richer pictures of life in the past.

The cases detailed in this volume challenge many assumptions about the materiality of households and our interpretations of households’ material remains. Overwhelmingly, the materiality of households is variable. For example, at Caylán (chapter 3) and Wasi Huachuma (chapter 4), residential structures were modified to meet the changing needs of variable household membership, while at Huaca Colorada (chapter 6), ritual modification of an archetypal house was central to social solidarity.

Practice: Households as Corporate Groups

In complement to the material definition of archaeological households, a practice-centered definition endures as well: households are corporate task groups. As task groups, households are taken to be the fundamental social units of production, distribution, transmission, and reproduction (Wilk and Rathje 1982). These abstract tasks take specific forms such as dwelling and decision-making (Blanton 1994, 5); attached, independent, or embedded specialization (Costin 1991a; Janusek 1999); making pots and brewing beer (Jennings and Chatfield 2009; Pacifico 2014); scheduling (Salomon 2004, 46); selective consumption (Burger 1988, 133); ritual practice (chapter 8; Vogel 2003, 2012), and managing the domestic economy of household members (Hirth 2009). Focusing on households as corporate groups has honed attention on bottom-up reconstructions of life in the past, often invoking the domain of everyday life. Much of today’s household research focuses on the individuals who make up the household and the interactions between them and the rest of the community.

Practice-based strategies in household archaeology reveal intrahousehold complexities. At the most basic level, households are made up of people going about their daily lives. People are rational actors making active choices about their subsistence, social, and political strategies (Cowgill 2000). Household members are inherently interdependent but do not always act with regard to the greater good of the group because “the domestic group consists of social actors differentiated by age, gender, role, and power whose agendas and interests do not always coincide” (Hendon 1996, 48). Households provide an arena in which to explore the physical remains of past individuals’ actions, because people have the most control over their daily activities, the majority of which likely take place within and near residential spaces. Therefore, this arena of investigation provides insight into the domain in which people make the most personal decisions pertaining to their well-being and that of fellow household members. For example, the use and deposition of gendered personal artifacts in and around the house suggests strong intrahousehold reproduction of gender identities and gendered practices (chapter 5). Other household practices were variable in response to external and internal forces. While the materiality of houses at Caylán (chapter 3) likely shifted in response to household need, at Pedregal (chapter 8) some household economic practices shifted under the demands of new Chimú overlords, while other household practices remained the same. Household practices also served as corporate strategies used to signal affiliation (at Ventanillas in chapter 8) and autonomy (at Talambo in chapter 9).

Scale: Household, Community, and Neighborhood

Households rarely exist in isolation, and so it is essential to consider the scalar relationships households shared with wider communities. Methodologically, household archaeology shares interests (and often overlaps) with community archaeology and the archaeology of neighborhoods. Both communities and neighborhoods incorporate households. Communities may not necessarily entail clear material correlates or physical spaces, as communities are often defined in large part by ideational components, such as a sense of belonging, conception of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- 1. Diverse, Dynamic, and Enduring: Ancient Households on the North Coast of Peru

- 2. New Directions in Household Archaeology: Case Studies from the North Coast of Peru

- 3. Cercaduras and Domestic Urban Life in Early Horizon Nepeña, Coastal Ancash

- 4. Communities in Motion: Peripatetic Households in the Late Moche Jequetepeque Valley, Peru

- 5. Figures of Moche Past: Examining Identity and Gender in Domestic Artifacts

- 6. Pillars of the Community: Moche Ceremonial Architecture as Symbolic Household at Huaca Colorada, Jequetepeque Valley, Peru

- 7. Households and Urban Inequality in Fourteenth-Century Peru

- 8. Continuity and Change in Late Intermediate Period Households on the North Coast of Peru

- 9. Enduring Collapse: Households and Local Autonomy at Talambo, Jequetepeque, Peru

- 10. Diversity in North Coast Households: Rethinking the Politics of the Everyday

- Contributors

- Index