eBook - ePub

Writing Their Bodies

Restoring Rhetorical Relations at the Carlisle Indian School

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Between 1879 and 1918, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School housed over 10,000 students and served as a prototype for boarding schools on and off reservations across the continent. Writing Their Bodies analyzes pedagogical philosophies and curricular materials through the perspective of written and visual student texts created during the school's first three-year term. Using archival and decolonizing methodologies, Sarah Klotz historicizes remedial literacy education and proposes new ways of reading Indigenous rhetorics to expand what we know about the Native American textual tradition.

This approach tracks the relationship between curriculum and resistance and enumerates an anti-assimilationist methodology for teachers and scholars of writing in contemporary classrooms. From the Carlisle archive emerges the concept of a rhetoric of relations, a set of Native American communicative practices that circulates in processes of intercultural interpretation and world-making. Klotz explores how embodied and material practices allowed Indigenous rhetors to maintain their cultural identities in the off-reservation boarding school system and critiques the settler fantasy of benevolence that propels assimilationist models of English education.

Writing Their Bodies moves beyond language and literacy education where educators standardize and limit their students' means of communication and describes the extraordinary expressive repositories that Indigenous rhetors draw upon to survive, persist, and build futures in colonial institutions of education.

This approach tracks the relationship between curriculum and resistance and enumerates an anti-assimilationist methodology for teachers and scholars of writing in contemporary classrooms. From the Carlisle archive emerges the concept of a rhetoric of relations, a set of Native American communicative practices that circulates in processes of intercultural interpretation and world-making. Klotz explores how embodied and material practices allowed Indigenous rhetors to maintain their cultural identities in the off-reservation boarding school system and critiques the settler fantasy of benevolence that propels assimilationist models of English education.

Writing Their Bodies moves beyond language and literacy education where educators standardize and limit their students' means of communication and describes the extraordinary expressive repositories that Indigenous rhetors draw upon to survive, persist, and build futures in colonial institutions of education.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Writing Their Bodies by Sarah Klotz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & History of Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Plains Pictography and Embodied Resistance at Fort Marion

Following the Buffalo War of 1874–1875, Plains nations found their lifeways decimated. Buffalo were integral to life for the Kiowa, Cheyenne, and other Plains tribes, so when federal troops slaughtered herds to the point of near extinction, starvation and exhaustion led to a series of captures and surrenders by these nations at Fort Sill (what is currently Oklahoma) (Earenfight 2007a, 12). As Kiowa writer N. Scott Momaday (Momaday and Momaday 1998, 1) explains, “The buffalo was the animal representation of the sun, the essential sacrificial victim of the Sun Dance. When the wild herds were destroyed, so too was the will of the Kiowa people.” A fragile peace agreement between tribal leaders and the US Department of War stipulated that thirty-three Cheyenne, twenty-seven Kiowa, nine Comanche, two Arapaho, and one Caddo warrior were to be exiled indefinitely to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida (Earenfight 2007a, 17). On April 28, 1875, the men were shackled and put in wagons with Black Horse’s daughter Ah-kes and wife, Pe-ah-in, who jumped into his wagon as the caravan departed to begin the 1,000-mile journey east (Glancy 2014, 2). Also imprisoned was a Cheyenne woman, Mo-chi, or Buffalo Calf Woman, who was charged with striking a white man on the head with an ax (Mann 1997, 40). On May 21, the caravan arrived in Florida and Richard Henry Pratt began his program of education in military training and English literacy. He cut the prisoners’ hair, dressed them in military uniforms, and brought in local schoolteachers to give literacy lessons. The prisoners lived in small cells, called casemates. During the first few months, they only saw the sky from the courtyard at the center of the fort.

Two years later, Pratt had gained fame for civilizing the savage warriors. Fort Marion drew the attention of social reformers including Harriet Beecher Stowe, who visited St. Augustine in the spring of 1877. She wrote about the visit for the Christian Union, describing a prison service where she observed a prayer led by the Cheyenne elder Minimic:

The sound of the prayer was peculiarly mournful. Unused to the language, we could not discriminate words: it seemed a succession of moans, of imploring wails; it was what the Bible so often speaks of in relation to prayer, a “cry” unto God; in it we seemed to hear all the story of the wrongs, the cruelties, the injustice which had followed these children of the forest, driving them to wrong and cruelty in return. (Stowe 1877, 372)

In her re-telling, Stowe displays long-held settler beliefs about Indians. She conjures what can only be described as Minimic’s noble savagery, a trope that Philip J. Deloria (1998, 4) argues “both juxtaposes and conflates an urge to idealize and desire Indians and a need to despise and dispossess them.” The Indians prisoners are incomprehensible to Stowe, but their worship harkens back to a primitive, Old Testament appeal to God. They are victims. They are children who should have been protected by a benevolent, paternal American nation and instead were harmed. They have been led astray by the cruelty of the colonial power. The phrase “children of the forest” comes from a nineteenth-century literary tradition of proclaiming the inevitable disappearance of Indian nations. Stowe draws upon such writers as James Fenimore Cooper, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Lydia Maria Child with her rhetoric of childlike and noble Indians who need to be protected and educated by the US government.

But there are no forests on the Southern Plains, and these are prisoners of war, not children. The men held at Fort Marion experience the post-bellum iteration of what Deloria (1998, 5) calls “a two-hundred-year back-and-forth between assimilation and destruction.” Finding themselves caught between these two impossible options, they perform Indian identity to appease their captors. According to Stowe, Minimic turns to his Euro-American audience after the prayer to translate. He tells his white audience that “they thanked the Great Spirit that he had shown them a new road, a better way; opened their eyes to see and their ears to hear. They wanted to go again to their own land, to see their wives and children and to teach them the better way” (Stowe 1877, 372). Even as Stowe attempts to map the prisoners into her conceptual framework of noble savagery, the prisoners retain a collective voice as they push back, demanding that their captors recognize their petition to return to their homelands. Their incarceration represents a particularly cruel and arbitrary action on the part of the US government because “from the Cheyenne perspective . . . banishment or isolation was the sentence for intratribal murder, the most extreme . . . behavior in their social structure. Thus, symbolically this separation sundered their very social fabric” (Mann 1997, 40–41). As I argue throughout this chapter, these demands enter the colonial discourse through Plains rhetorical traditions that prisoners adapt to address their changing circumstances. That is, when Minimic performs at a Christian prayer service, he does so in his own language and then strategically translates his speech into a petition. Fighting to preserve the Cheyenne territory is the very reason Minimic and his fellow prisoners are captives. His speech advances ongoing Cheyenne campaigns to maintain their ancestral territory.

The rest of Stowe’s article describes how the prisoners have learned to value industry and given up their nomadic ways. She argues for a new national commitment to Indian education to prevent further bloodshed. She praises the prisoners for wanting to farm, blacksmith, and bake bread. She references Japanese students attending the Amherst State Agricultural School (now the University of Massachusetts Amherst) as a model for the cultural education the Indian men might pursue after their captivity. Stowe’s brief essay is prophetic of the shifting role of education in American imperialism. Shortly following the publication of this piece, Colonel Richard Henry Pratt opened the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which introduced the English-only paradigm to Native children from New England to Alaska. Even Puerto Rican and Filipino children were subject to Pratt’s English-only program following the Spanish-American War. The Fort Marion prisoners experienced the earliest form of this paradigm shift, and for that reason, the rhetorical history of the Carlisle school begins here.

This chapter looks at the rhetoric of relations deployed by Fort Marion prisoners as they work to demonstrate their futurity on the shifting rhetorical ground of settler colonization. As the Fort Marion prisoners and, later, the Carlisle students demonstrate, Native nations are not fading away or growing out of their indigeneity through education. They are present and will continue to be present long after the scourge of European settler colonization has ended. The relational rhetorics of Fort Marion prisoners make material Indigenous corporality and futurity by engaging what Beth Piatote (2013, 9) has called “an anticolonial imaginary: visions of alternative futures that may explain, in part, how Indian communities survived the violence of the assimilation era.” The Fort Marion prisoners make visible the violence of Pratt and the US government. They engage in performances of personal sacrifice for the benefit of the group. The individual prisoners may not have a future, but their texts, their communities, and their land bases do. This is the story Minimic and his fellow prisoners tell in media ranging from pictographic sketches to the Sun Dance rituals to suicide attempts. Most important, this is a story about the affordances of relational rhetorics of the Southern Plains and how those rhetorical traditions allowed the prisoners at Fort Marion to resist their captivity while preserving their stories for the future use of their nations.

From Savage to Student: Rhetorical Constructions of the Indian in the Assimilation Era

Richard Henry Pratt is recognized as the founder of the off-reservation boarding school movement, but his experiences in Indian education actually began at Fort Marion in 1875. He was tasked with holding seventy-two prisoners from the Southern Plains for an indefinite period. In his autobiography, Pratt suggests that his model for Indian education emerged out of circumstance and improvisation; he implemented military-style discipline and English-literacy education to both control and occupy the prisoners during their incarceration. Alongside his laissez-faire narrative about the invention of a model for assimilationist education, however, Pratt begins to articulate the larger context that guided his actions. Pratt saw himself as an advocate for justice. He wanted to bring about “the rights of citizenship including fraternity and equal privilege for development” of the Indian (Utley 1964, xi). He felt that reservations unjustly segregated Native Americans and kept them from entering into the social goods enjoyed by US citizens. Underlying these moral claims is also a shifting approach to Indian affairs in the federal government. As allotment policies gained traction, Pratt’s moral stance against Indian segregation resonated with the federal government’s desire to break up reservation land and open further territory for resource extraction and settlement. Like so many language and literacy educators, Pratt worked within a fantasy of benevolence. He viewed his role as separate and distinct from the settler project of resource acquisition and upheld that view by constructing a trope of the Indian to fit a new age of settler colonization.

The figure of the Indian student was not new. In fact, it drew its particular power from building on long-held tropes of the Indian in US cultural productions. In American literary and legal texts, Native Americans are figured as noble savages, disappearing Indians, children of the forest, domestic dependent nations, and, at the end of the nineteenth century, students. As Jean O’Brien (2010, xxi) has argued, these tropes engage a temporality that holds Native peoples outside of modernity. The noble savage is pre-modern. The disappearing Indian vanishes to avoid becoming modern. The domestic dependent nation, a concept articulated in the 1831 Cherokee Nation v. Georgia decision, posits that the Cherokee cannot become modern as sovereign nationals but must enter modernity as childlike dependents of more advanced settler citizens. The ruling also places tribal political organizations “in a state of pupilage,” confining Indigenous peoples to a student-like status in relation to their benefactor, the United States (Piatote 2013, 5). The Indian student is related to these earlier tropes (as a perpetual child, for example), but this is a youth who can learn to approximate European cultural maturity. The Indian as student acts as a convenient figure to justify policies of forced assimilation.

The Indian as student was particularly suited to colonial desires of the late nineteenth century when the end to the Civil War created an increased demand for national unity, a tension that had historically been eased by moving the frontier ever-westward to open land and resources to disaffected whites.1 By rhetoric here I follow John Duffy’s (2007, 15) definition: “the ways of using language and other symbols by institutions, groups, or individuals for the purpose of shaping concepts of reality.” Rhetorical theory is a crucial and underutilized lens to understand how literacy, media, and education reinforce settler-colonial dominance. Under settler-colonialism, the moral authority of the settler state must be shored up by the unremitting obfuscation of a simple fact: settlers occupy a land base to which they have no historical claim. Scholars of literature, American history, and performance studies have done excellent work in delineating how this obfuscation happens in novels, poems, the legal system, and diplomatic ceremonies. And yet, rhetoric has not been fully embraced to make sense of the persuasive nature of intercultural contact in the Americas—the ways encounters between settler and Indigenous peoples play out as a negotiation of cultural and military dominance. Nor have we fully considered how intercultural communication in colonial encounters is embodied. As Jay Dolmage (2014, 5) has argued, “We should recognize rhetoric as the circulation of discourse through the body.” In the day-to-day negotiation of power, culture, and control at Fort Marion, assimilation and resistance were embodied processes. Rhetoric lends insight into how bodies make meaning. Through rhetoric, we can interrogate the paracolonial sites of the military prison and the boarding school (see Vizenor 1994, 77).

Fort Marion and Carlisle also illuminate how myths of Indian identity permeated the public sphere of the United States in the nineteenth century, making new forms of colonial violence not only imaginable but justifiable as well. Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang (2012, 9) have delineated common settler moves to innocence: myths or tropes that enable “a settler desire to be made innocent, to find some mercy or relief in [the] face of the relentlessness of settler guilt and haunting.” The figure of Indian as student certainly falls within this framework and demonstrates how settlers in the late nineteenth century wished to absolve themselves of colonial guilt while pushing forward ever-accelerating forms of domination and land theft. I would argue that settler moves to innocence are best understood as rhetorical—that is, persuasive—invested in defining reality in terms that benefit settler-colonialism. As Lisa King (2015, 25) has argued, constructions of Indians and savagism work as Burkean terministic screens through which non-Native communities function. During the Plains Wars, settler culture constructed the Indian as a violent savage who presented an existential threat to the United States. For Pratt, the Indian was not inherently evil, only hindered by his culture and language. Pratt amplified the trope of Indian as student of civilization to replace the trope of Indian as violent, savage warrior, but both terministic screens have the same effect: the murder and dispossession of Indigenous peoples. If Indians were savage warriors, they could be killed in war as enemy combatants. If Indians were students learning to be fully American, then their language, kinship, and land rights were as malleable as their uncultivated minds. Unlike treaty agreements that posited two equal nations in diplomatic relations, the Indian as student figure allowed the US government to circumvent existing treaty arrangements in the name of well-meaning paternalism. In this way, the fantasy of benevolence engaged by literacy educators became a colonial tactic working in concert with more explicitly violent forms of domination.

The Indian as student was compatible with perhaps the most persistent myth in the settler imaginary: the disappearing Indian. The boarding school movement promised a new type of disappearance; rather than fading naturally and willingly into the Western wilderness as Chingachgook does in James Fenimore Cooper’s novel The Last of the Mohicans, these Indians will disappear through education. This new iteration of the disappearing Indian myth served to justify new forms of US colonial violence—it was the dysfunctional and anachronistic culture of the Indian that led to his fading presence on the land, not the slaughter of peoples and buffalo on the Southern Plains. Gerald Vizenor (1994, ix) has theorized Indians such as Chingachgook as “immovable simulations, the tragic archives of dominance and victimry.” These Indians are represented and reproduced through manifest manners, the “racialist notions and misnomers sustained in archives and lexicons as ‘authentic’ representations of indian cultures” (vii). Through the concept of manifest manners, Vizenor has articulated how language shores up settler colonialism. The primary mechanism of that shoring up is the static and unchanging Indian who loses his claim to nation, land, and language by deviating from settler perceptions of the traditional, static, and authentic. Pratt’s vision of the Indian student was a late nineteenth-century iteration of these manifest manners.

Pratt propagated the myth of the static, authentic, and disappearing Indian by obsessively chronicling the cultures and bodies of his prisoners. He took pains to photograph them in their tribal attire upon arrival at Fort Marion, encouraged them to perform dances for St. Augustine audiences, copied and translated a pictographic letter written by Manimic2 for posterity, and solicited sculptor Clark Mills to come from Washington, DC, to make life casts of the Indians’ heads for preservation and scientific study at the Smithsonian Institution (Glancy 2014, 38).3 Philip Deloria (1998, 90) has called this impulse “salvage ethnography—the capturing of an authentic culture thought to be rapidly and inevitably disappearing.” Importantly, salvage workers like Pratt must confront a contradiction. He has to believe “in both disappearing culture and the existence of informants knowledgeable enough about that culture to convey worthwhile information” (Deloria 1998, 90). Pratt faces another paradox: he is working to stamp out the tribal cultures he also wants to preserve. As was the case with many writers and politicians before him, a trope of the Indian fills this gap in logic. As Vizenor (1994, 11) argues, “Dominance is sustained by the simulation that has superseded the real tribal names.” Pratt conceives of the Indian as a student to meet the burden of maintaining American national innocence. His fantasy of benevolence requires Indians to be figured as culturally childlike. Education supersedes alternative policies such as upholding treaties, segregating and confining Indians on reservations, or subduing Indians through war.

Through education, Pratt was convinced that the Indian could become the same as, or similar to, the white man. For the federal government, this particular trope of the Indian student justified not only the breaking of treaties in the Southern Plains but also ongoing westward expansion and land theft. Long viewed as a solution to the “Indian Problem,” reservations now came under attack as segregated spaces keeping Indians from reaching the full potential of American citizenship. Pratt’s reframing of Indian as student made way for the off-reservation boarding school system, which in turn amplified and spread allotment policies that reproduced private land ownership, nuclear family kinship structures, and English-language dominance. Pratt’s myth of the Fort Marion prisoners, that he could transform fierce Indian savages into receptive students, laid the groundwork for the assimilation and allotment project that would drive Indian policy for the next century.

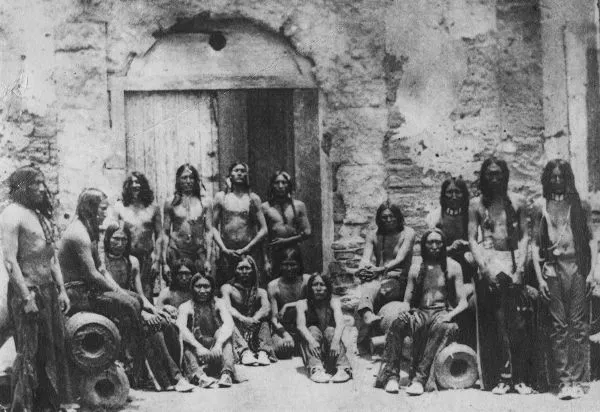

Figure 1.1. Plains Indian prisoners arriving at Fort Marion, Florida, ca. 1875. Photographer unknown. Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

We can see this shift from savage to student entering the public imagination through Pratt’s famous before-and-after photographs. As Hayes Peter Mauro (2011, 2) has argued, the logic of assimilation “could be visu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Toward a Rhetoric of Relations

- 1. Plains Pictography and Embodied Resistance at Fort Marion

- 2. Plains Sign Talk: A Rhetoric for Intertribal Relations

- 3. Lakota Students’ Embodied Rhetorics of Refusal

- 4. Writing Their Bodies in the Periodical Press

- Afterword: Carlisle’s Rhetorical Legacy

- Notes

- References

- About the Author

- Index