eBook - ePub

Building Future Health and Well-Being of Thriving Toddlers and Young Children

95th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, September 2020

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Building Future Health and Well-Being of Thriving Toddlers and Young Children

95th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, September 2020

About this book

The early child period is considered the most important developmental phase throughout the lifespan. The 95th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop explored in some detail the current scientific research, challenges, and opportunities of cementing a healthy foundation for life in toddlers and young children. The workshop brought together experts in the areas of health care, public health, and developmental science. The first session focused on the nutritional challenges in toddlers and young children across the globe, such as overweight and obesity. The theme of the second session elucidated the journey from infancy to toddlerhood and the role of nutrition in it, focusing social aspects. And finally, the third session aimed to explain the steps of motor skill development and the role of physical activities and nutrition in cognitive development and learning abilities of a child. The key issues offer valuable insights for health care providers, policy makers, and researchers on how appropriate nutrition, nurturing caregiving, and environment can influence the development and health of children up to 5 years of age.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building Future Health and Well-Being of Thriving Toddlers and Young Children by Maureen M. Black,Atul Singhal,Charles H. Hillman,M.M. Black,A. Singhal,C.H. Hillman,Maureen M., Black,Atul, Singhal,Charles H., Hillman, Maureen M. , Black,Atul, Singhal,Charles, Hillman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nutrition, Dietics & Bariatrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Advancing from Infancy to Toddlerhood through Food

Published online: November 9, 2020

Black MM, Singhal A, Hillman CH (eds): Building Future Health and Well-Being of Thriving Toddlers and Young Children. Nestlé Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. Basel, Karger, 2020, vol 95, pp 54–66 (DOI: 10.1159/000511517)

______________________

Transition from Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding to Toddler Nutrition in Child Care Settings

Lorrene D. Ritchiea Danielle L. Leea Elyse Homel Vitaleb Lauren E. Auc

aDivision of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Nutrition Policy Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA; bStrategy and Operations, Child Care Food Program Roundtable, Los Angeles, CA, USA; c Department of Nutrition, University of California, Davis, CA, USA

______________________

Abstract

Child care has broad reach to young children. Yet, not all child care settings have nutrition standards for what and how foods and beverages should be served to infants as they transition to toddlerhood. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development of nutrition recommendations to guide feeding young children in licensed child care settings in the USA, a process that could be adapted in other countries. Nutrition standards were designed by nutrition and child care experts to address what and how to feed young children, also including the transition from infants to toddlers. Nutrition standards are important for health and can be feasibly implemented in child care settings. Feasibility considerations focused on family child care homes, which typically have fewer resources than child care centers or preschools. Infant standards include recommendations for vegetables, fruits, proteins, grains, and breast milk and other beverages. Also included are recommendations for supporting breastfeeding, introducing complementary foods, and promoting self-regulation in response to hunger and satiety. Toddler standards are expanded to address the frequency as well as types of food groups, and recommendations on beverages, sugar, sodium, and fat. Feeding practice recommendations include meal and snack frequency and style, as well as the promotion of self-regulation among older children.

© 2020 S. Karger AG, Basel

Importance of the Infant to Toddler Transition

Obesity among US children 2–5 years old has nearly tripled from 5% in 1976 to 14% in 2016 [1]. Dietary risk factors for obesity begin in infancy when energy intakes begin to exceed recommendations [2]. Although rates of breastfeeding have improved in recent years [3], most infants in the USA are bottle fed at some point in the first year of life, and 10–20% are introduced to complementary foods prior to the recommended 4–6 months of age [2–4]. As infants transition into toddlers, dietary patterns worsen and are characterized by inadequate intake of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and excessive consumption of sugar-sweetened foods and beverages [5]. For example, in a 2008 study, 16–27% of infants 9–12 months old transitioning into toddlers up to 23 months of age did not consume any fruit on a given day. In contrast, intake of sweetened foods tends to increase rapidly as an infant transitions into toddlerhood resulting in as many or more children consuming a sweetened food than a fruit or vegetable on a given day by the second year of life [2, 6]. By the end of toddlerhood, dietary intakes tend to be established, becoming habits that track into later life [2]. Despite the importance of early life for subsequent nutrition and health, the evidence-based recommendations for the nation, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, do not currently include guidance for young children 0–2 years of age [7].

Role of Child Care in Infant and Toddler Nutrition

Given that over 1 in 5 US children are already overweight or obese before entering kindergarten [1], interventions in the youngest children are essential. Licensed early care and education settings (hereafter referred to as child care) are the largest institutional settings in the USA for improving nutrition among young children. Since the 1970s, the rate of employment by mothers of children under 3 years old has nearly doubled [8]. In 2018, among families with children 0–5 years old, both parents were employed in 58% of households of married couples, and 69% of mothers and 85% of fathers were employed in single-parent households [9]. Concurrent with rates of parent employment, use of child care has risen. Over one-third of all young children spend time in organized, licensed child care (as opposed to informal care with family, friends, or neighbors) [10]. Many young children attend child care for a long day that matches their parent’s employment, where they consume much of their daily nutrition [11].

Studies have found mixed associations between attending child care and child obesity [12–14]. For example, in a systematic review of observational studies conducted in developed countries, 3 studies found center-based care associated with increased prevalence of child overweight or obesity, 8 studies found no association, and 2 studies found a protective relationship [12]. Enrollment in full-day child care at an early age (<3 months) has been associated with less breastfeeding and early introduction of complementary foods [15]. Disparities in findings may be partially explained by the timing of exposure to child care. Studies suggest that more time spent in child care, especially during the transition from infancy to toddlerhood in the first and second years of life, is a risk factor for child obesity [13, 14].

In the USA, the federal Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) provides reimbursements to child care centers and homes for up to a total of 3 meals and snacks per day to provide specific types and amounts of food groups [16]. However, relatively few licensed child care facilities participate in this program. In California, for example, which accounts for one-seventh of the US population, only about one-third of young children in licensed child care were at facilities that participate in CACFP [17]. Further, CACFP standards do not regulate foods or beverages that are not claimed for reimbursement and do not specify how children should be fed (e.g., feeding practices). Outside of CACFP, there are no federal nutrition requirements and incomplete and inconsistent state-by-state nutrition requirements to which licensed child care facilities are subject [18]. Few states, for example, have comprehensive standards to support breastfeeding and other recommended early feeding practices in child care [19, 20].

In the USA, licensed facilities can vary from small, family child care homes with a single provider and a few children to large centers or preschools with a director, multiple teachers, and several hundred children. There is concern that nutrition standards may be difficult to afford or implement, particularly by child care homes [21]. Child care homes are independently operated businesses in the homes of providers who often are low-income women with limited resources and opportunities to obtain nutrition training [22]. Further, nutrition in family child care homes tends to be less optimal than in centers or preschools [23].

Developing nutrition standards that are both evidence-based and feasible for implementation in child care settings is an important early step towards laying the groundwork for improving the nutrition of young children. As such, the purpose of this paper is to describe a process whereby evidence-based nutrition standards for young children in child care were developed and refined so that they would be actionable and achievable in most child care settings in the USA, including family child care homes. This process may be adapted to establish or refine nutrition standards for child care settings in other countries.

Development of Child Care Nutrition Standards for Infants and Toddlers

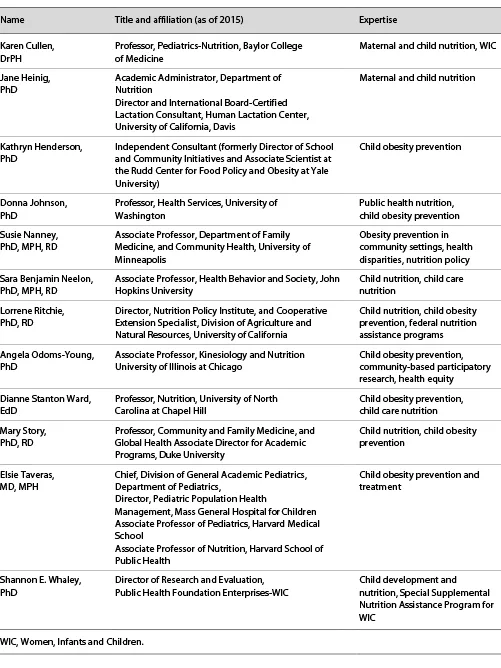

Starting with current guidelines from authoritative bodies, in 2015 standards were refined by both nutrition experts and child care practice-based stakeholders. Science advisors (Table 1) from across the country were selected based on their scientific expertise in nutrition and obesity prevention for children and in child care. They were tasked with developing a comprehensive set of evidence-based nutrition recommendations for: (1) infants from birth up to 1 year of age, and (2) children over 1 year. Science advisors were asked not to include practical considerations of child care settings in their deliberations but focus on standards optimal for child health.

Child care recommendations were first selected from authoritative bodies that had put forward nutrition recommendations for child care settings. These included the CACFP standards [16]; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics [24]; Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care Best Practices [25]; Institute of Medicine [26]; 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans [7]; American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association and National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education’s Caring for Our Children [27]; and Nemours [28]. Recommendations on whatfoods and beverages should be offered (dietary intake) as well as howthe recommended foods and beverages should be offered (feeding practices) were compiled.

The recommendations were tabulated from each expert body and organized by dietary intake of food group (e.g., fruit juice, other fruit, or vegetable) and feeding practices (e.g., breastfeeding or meal service). There were 25 infant nutrition recommendations and 173 child nutrition recommendations identified. To help expedite the process, the most comprehensive nutrition recommendations for each food group or feeding practice were selected prior to the expert convening. Using a Delphi process, group consensus was reached among the science advisors by discussing each highlighted standard and identifying additions, deletions, or revisions. After the completion of this group consensus process, each science advisor independently ranked the nutrition standards according to potential impact (high, medium, and low) on child nutrition, obesity, and health. The science advisor rankings were compiled, and the standards separated into 3 groups according to the following criteria:

•High impact: 70% or more of science advisors ranked as high impact and no science advisor ranked as low impact

•Medium impact: mixed responses from science advisors in between high and low

•Low impact: over 30% of science advisors ranked as low impact, and no science advisor ranked as high impact, or over 50% ranked as low impact.

Table 1. Science advisors involved in the development of infant and toddler nutrition standards for child care

The next step involved convening an independent group of child care community advisors to review the final set of nutrition standards compiled by the science advisors. The child care community advisors included representation from child care advocates, CACFP sponsoring agencies (who provide training and technical assistance to child c...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Front Matter

- Challenges in Nutrition in Toddlers and Young Children

- Advancing from Infancy to Toddlerhood through Food

- Health Behaviors and the Developing Brain

- Subject Index