eBook - ePub

The Civilian Conservation Corps in Nevada

From Boys to Men

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Great Depression of the 1930s had a devastating impact on sparsely populated Nevada and its two major industries, mining and agriculture. Luckily, thanks to Nevada's powerful Senate delegation, Roosevelt's New Deal funding flowed abundantly into the state. Among the programs thus supported was the Civilian Conservation Corps, a federal program intended to provide jobs for unemployed young men and a pool of labor for essential public lands rehabilitation projects. In all, nearly thirty-one thousand men were employed in fifty-nine CCC camps across Nevada, most of them from outside the state. These "boys," as they were called, went to work improving the state's forests, parks, wildlife habitats, roads, fences, irrigation systems, flood-control systems, and rangelands, while learning valuable skills on the job. Rural communities near CCC camps reaped additional benefits when local men were hired as foremen and when the camps purchased supplies from local merchants.

The Civilian Conservation Corps in Nevada is the first comprehensive history of the Nevada CCC, a program designed to help the nation get back on its feet, and of the "boys" who did so much to restore Nevada's lands and resources. The book is based on extensive research in private manuscript collections, unpublished memoirs, CCC inspectors' reports, and other records. The book also includes period photographs depicting the Nevada CCC and its activities.

The Civilian Conservation Corps in Nevada is the first comprehensive history of the Nevada CCC, a program designed to help the nation get back on its feet, and of the "boys" who did so much to restore Nevada's lands and resources. The book is based on extensive research in private manuscript collections, unpublished memoirs, CCC inspectors' reports, and other records. The book also includes period photographs depicting the Nevada CCC and its activities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Civilian Conservation Corps in Nevada by Renée Corona Kolvet,Victoria Ford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Nevada PressYear

2015Print ISBN

9780874179934, 9780874176766eBook ISBN

9780874176896PART I

The Nation, Nevada, and the New Deal

1

A Nation Brought to Its Knees

I was just out of high school in 1935, and most everybody was in the same boat that I was . . . farm boys. . . . My dad was hoboing in Canada. He saved every penny he made up there. . . . The idea when I originally enrolled was, the money I would make there [CCC], the folks were going to lay away for me, and I could go to college when I got out, which I wanted to do desperately. . . . Things were so bad that for a year and a half my parents, my brother, and my three sisters lived on my $25, so there was never a chance of me ever going to college.

—Ralph Hash (Camp Newlands)

Like millions of young men, Ralph Hash graduated from high school only to find that there were no job opportunities or money available for a college education.1 Worse yet, there were no job prospects on the horizon. American leaders feared for the future of this generation and with good reason—nearly fifteen million unemployed men were under the age of twenty-five. Of all Americans, young men were most affected by the Great Depression.

The Depression had entered its fourth year when Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office. Although he originally believed that relief was best handled by local and state agencies, the lingering economic stagnation forced him to reconsider his position. Big problems required big measures: the president decided that massive federal intervention was necessary to combat a crisis of such magnitude.2 From that one starting point, his New Deal programs followed no single philosophy. He adopted some programs from the Hoover administration, and created others to alleviate emergencies or aid particularly depressed regions of the nation. A few New Deal programs such as social security have survived into the present, while others died along with the New Deal, as did the CCC.3

Most scholars will agree that New Deal programs offered hope and security to a nation gripped by fear and uncertainty. Public optimism soared when FDR pledged he would lead the country out of economic paralysis. His decisiveness and optimism alone inspired the American people.4 The president’s programs were structured to assist the economic fabric of the entire country and its people—from minorities, farmers, and recent immigrants to employers, bankers, and capitalists.

Roosevelt wasted no time in setting the wheels in motion, and the achievements of the Hundred Day Congress were impressive by any standard. All fifteen of the president’s requests to Congress were signed into law by June 16, 1933. After tackling the banking crisis, cutting five hundred million dollars from the federal budget, and signing the Beer-Wine Revenue Act, he turned his attention to unemployment payments and other forms of relief. He created two new agencies: the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) and the Civilian Conservation Corps under the auspices of the Emergency Conservation Work agency. Although the statutory CCC was not created until June 28, 1937, the name Civilian Conservation Corps was used by the president and CCC officials with the creation of the ECW in March 1933. Their creation represents the first direct federal involvement in unemployment relief and welfare services in our nation’s history.5

With Public Bill no. 5, the Seventy-third Congress created the ECW; the president signed it on March 31, 1933. Four years later, Congress passed and the president signed Public Bill no. 163, and the Seventy-fifth Congress reestablished the CCC for three more years beginning July 1, 1937. By then, seventeen- to nineteen-year-old enrollees represented 73 percent of the overall force. The youthful nature of the corps led to serious plans for a permanent CCC.6 The CCC became one of the most popular New Deal innovations, designed to salvage two of the nation’s most threatened assets—our young men and natural resources.7 The CCC provided vocational training and full-time employment in a healthy outdoor environment. The program targeted unmarried men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five (later expanded to include seventeen to twenty-eight year olds) living on public or private welfare and literally walking the streets hungry. Joseph Ruchty (of Camp Carson River) recalled the discouragement he felt while looking for work in Newark, New Jersey, in 1938. He had dropped out of junior high school to find a job and help his family:

I struck out to go look for work with another fellow named Felix Lavertano. After looking . . . I said, “We’re not going to find any work.” We went down to the [Jersey] Shore and looked in places, and nobody was hiring . . . anybody. I used to stop at Edison’s factory every morning until the guy, McCoy, knew me by sight. And when he’d see me coming in the door, he used to wave at me and say, “Hit the road.” No jobs . . . When we came back home, then I went in the CC [sic] camps.8

The CCC helped solve another predicament—what to do with the “Bonus Army,” the group of World War I veterans who averaged forty years of age in 1933. Many of the veterans suffered from poor physical and mental health or battle-fatigue syndrome.9 Following the suggestion of veterans administrator Gen. Frank T. Hines, veterans were offered immediate employment with the CCC, which delayed wartime service bonuses that were demanded but not due until 1945.10 Although some veterans scoffed at the one dollar–a-day compensation, thousands joined the CCC and soon found themselves conditioning and transporting new enrollees to camps around the country.

FDR’s concept of shaping a sound environment while creating new jobs was nothing new. As governor of New York, he supported an amendment to the state constitution that culminated in the purchase and reforestation of one million acres of the state’s abandoned farmlands.11 On a national scale, Roosevelt was keenly aware of the environmental degradation that threatened the American countryside. Large expanses of public and private land suffered from massive neglect and shortsighted overuse. The Midwest and southeastern Atlantic seaboard were plagued by soil erosion, and Dust Bowl states lost precious topsoil due to poor farming practices. In the West, overgrazed rangelands and overcut forests coupled with droughts created conditions that were ripe for fire and erosion. By creating the CCC, the federal government provided environmental assistance to every state in the Union.

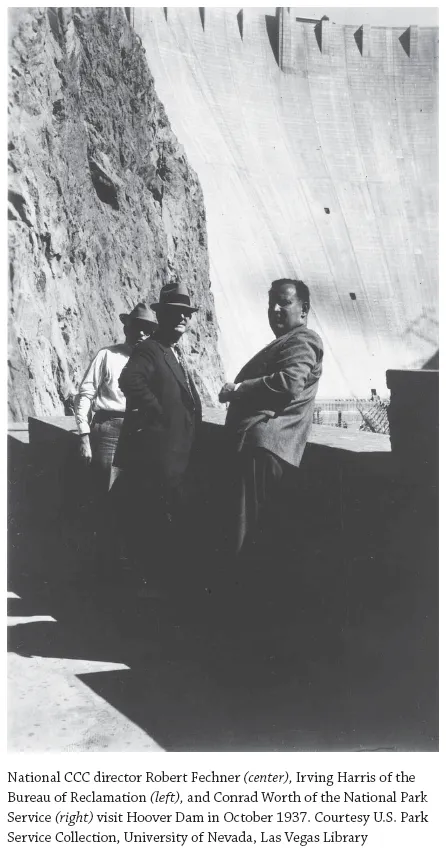

The sheer magnitude of mobilizing the CCC required synchronizing a huge workforce with a variety of government agendas. Executive Order 6101 required an advisory council to coordinate with the CCC director. The council consisted of one representative each appointed by the secretaries of war, agriculture, the interior, and labor. FDR appointed conservative labor leader Robert Fechner as the CCC’s national director. Fechner answered directly to the president, and the advisory council communicated with the president through the director.

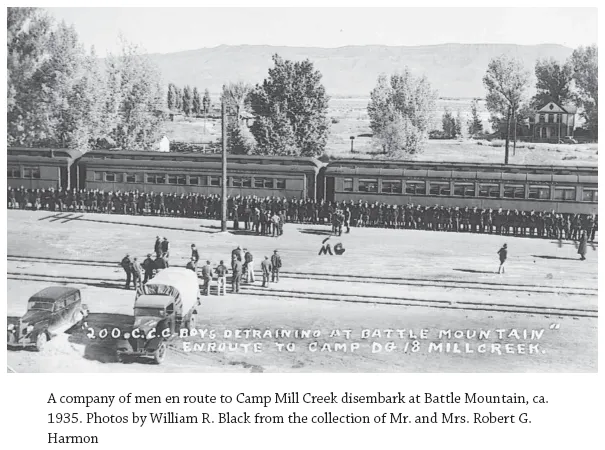

The president ordered that 250,000 unmarried men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five be enrolled by July 15, 1933. Ultimately, that number increased to 274,375. Initially, the U.S. Army’s role was to transport enrollees to the camps. It soon became apparent, however, that the army was best suited to running the camps. The army reluctantly agreed to the expanded role. The CCC also recruited 25,000 World War I veterans and another 25,000 local experienced men (known as LEMs) to train and supervise the inexperienced young men.

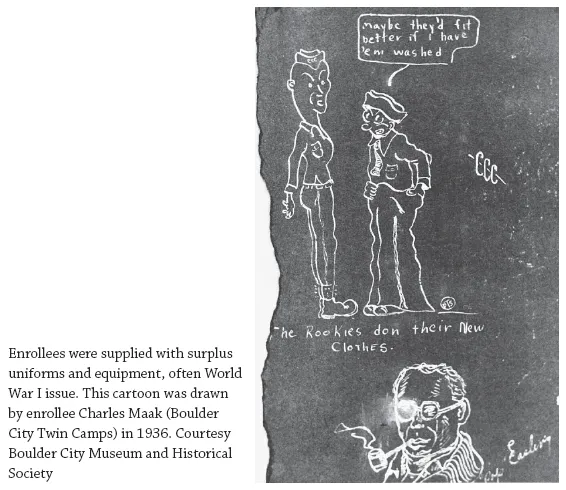

Enrollee Ralph Hash worked closely with military officers at Camp Newlands and recalls the unique relationship that the CCC had with the army: “We had regular army issue clothing, and army officers were our commanding officers, but it wasn’t operated exactly like the military. They were still the bosses and we had to tow the line. Probably the major penalty they could have given us, if we were unruly and couldn’t get along, they [would] just send us home.”12

To meet the president’s goal, 8,540 men had to be processed a day to occupy more than thirteen hundred “forest” camps nationwide.13 By early May, there was doubt as to whether the goal was realistic. Labor Department selection director W. Frank Persons discussed his concerns in a letter to Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins:

I was startled this afternoon when told by Colonel Major that he estimates . . . only five hundred forest camps will be in operation by July 15th. . . . [At this rate] it will be nearly the first of October before 250,000 men are at work. . . . You will recognize that the organization we have created for the selection of men is a mighty engine of public opinion. It embraces the influential citizens in every township in all of the forty-eight states. . . . Naturally they are interested in these boys. . . . They are likely to manifest very actively any dissatisfaction . . . because the implied promises . . . (that is, a job in the near future) cannot be fulfilled.14

A new executive order was issued to streamline the mobilization process. Under the revised plan, project superintendents, technical advisers, and superintendents hired by federal agencies would maintain jurisdiction over the enrollees during work hours, while military veterans and reservists would be in charge of the men while in camp. The order also relaxed purchasing and bid standards, required the Department of Labor to complete selection of men by June 7, gave the army greater discretion in disciplinary matters over recruits, and approved 290 additional work projects by June 1.15

The War Department proudly reported to the president that it had successfully executed “the greatest peacetime demand ever made of the Army” on June 30, 1933. The army had organized 73 stations for use as reconditioning camps and received and performed physicals on more than 270,000 men. Within a few short months, the army transported 55,000 men (in 353 company units) from the East Coast and Midwest to 159 destinations in seven western states. By the July 15 deadline, 4,685 army officers—including 1,672 organized reserves and 510 navy and marine corps officers—were performing full-time duty.16 Although a majority of enrollees served close to home, many were transported by train to destinations out West. Joseph Ruchty was one such person. Aspects of his selection and first trip out West were memorable, including the lack of sanitation.

Joseph Ruchty, Camp Carson River

Well, first you had to go and see . . . the overseer of the poor, Mary Nevills, and she wrote you up. . . . The next time they bring the allotment in, you go down to the Newark [New Jersey] Army. . . . It wasn’t like you join the armed forces where you had to pledge allegiance to the flag and everything. We all wanted to be with the flag anyway. [From Camp Dix] they march you down to the railroad station, and you had your bags packed. And this is summertime, and you had your ODs—the winter clothes—on and you were perspiring. . . .

You had old Pullman sleepers, you know. Two guys would sleep on the bottom; one guy sleeps on top. Everybody tried to get to the top . . . [because] you’re by yourself. Don’t forget now, these are coal-burner trains. . . . The mess car is in the center of the train, two of them. And there’s about four more cars on each side with recruits going into the camps. Now, they start with bringing the food to you. You got your old canteen cup, which was from World War I, and your mess kits were aluminum, World War I vintage, and you got that coffee. . . . Here comes the prunes. So by the time the next thing comes, the prunes [have] already been eaten. Then you get your bread, and then comes the apple butter. All it does is make the bread wet; apple butter was terrible. And then you got your eggs and potatoes. And then, that was it.

Now, you’re coming back with your food and your mess kit, and all this—looks like pepper’s getting over everything—it is cinders from the coal. So now you get back to your place, and you got quite a bit of cinders in your food.

Now, when you finish eating, here comes the . . . steaming hot water kettles. You dip your mess kits in there, right? Now, the grease is on the top, right? So when you pull it back up, the grease gets on it anyway. So you had to get into the washroom and do a little cleaning up with toilet paper. . . . But what the guys did, after each meal—they had the windows open because it was summertime—and they hit the side of your mess kit on the side of the train. Now when you got off that train, there was one streak of garbage all the way down.17

In a White House Press release dated July 3, 1933, an exuberant FDR announced that the goal of the American people had been met. He shared the following message to new enrollees in the ECW’s periodical, Happy Days:

It is my honest conviction that what you are doing in the way of constructive service will bring to you, personally and individually, returns, the value of which it is difficult to Estimate. . . . [Y]ou should emerge from this experience strong and rugged and ready for re-entrance into the ranks of industry, better equipped than ever. I want to . . . express to you my appreciation for the hearty cooperation which...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I - The Nation, Nevada, and the New Deal

- Part II - CCC Contributions and the Legacy Left Behind

- Appendix: Compilation of Nevada CCC Camps and Their Supervisory Agencies

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index