![]()

Chapter One

The Washoe Indians and the Lake

In the late nineteenth century the powerful Washoe shaman Welewkushkush used his powers for healing. Supernatural Water Babies, the most powerful of the Washoes' mythological beings, inhabited all rivers, lakes, streams, and ponds in the Washoe world. They were one of Welewkushkush's sources of power. Lake Tahoe, the center of the vast Washoe lands, was the center of the Water Babies' world as well. Legend held that the small, gray-skinned creatures used a tunnel running from the lake to travel to other bodies of water in the valleys of the eastern Sierra.

Once, on Tahoe's shore, Welewkushkush's apprentice collapsed, falling severely ill. Welewkushkush announced that one of the water beings had captured the apprentice's soul. He began chanting and shaking his rattle and entered the water. He proceeded until completely submerged. Witnesses, who included whites as well as Washoes, claimed the shaman remained underwater for some ten minutes. When he returned he instructed the apprentice's mother to shout the boy's name four times, and he circled the boy an equal number of times. The boy's nose began to bleed, a sign of supernatural power having touched him, and he regained consciousness. Welewkushkush turned the boy to the lake and instructed him to shake the rattle. The apprentice acted as if awakening from a dream. Welewkushkush had negotiated with the leader of the Water Babies for the boy's soul.

For thousands of years early in spring, as soon as melting snow allowed, the young and healthy Washoes traveled from their winter homes in the valleys adjoining the Sierra to the lakeshore. As the season progressed, those who took more time to travel, the elderly and perhaps mothers with babies or small children, followed. The three main branches of Washoes, the Welmelti from the North, the central Pawalti, and the Hangalelti from the South, took up residences encircling the lake for what was known as the “Big Time.” Various clans spent the summer months visiting and celebrating, the elders taking time to meet and plan the use of hunting and plant resources for the following year. In the fall, Trout Creek on the south shore became one of the most important of their areas. The fish taken there were prepared and carried out as fare to be consumed while gathering pine nuts in the Great Basin or acorns on the Sierra's western slope.

Upon their arrival at Daowaga, Washoes blessed the water that breathed life into their ecosystem. Throughout the summer, tribe members fished the lake and its tributaries, collected medicinal and food plants in its surrounding meadows, and, toward fall, hunted game on its mountainsides. The Upper Truckee River hosted a significant habitation site, one and a quarter miles from the lake on the river's east side. Washoes called the river ImgiwO'tha, imgi being cutthroat trout, wO'tha meaning “river.” It, and the streams that fed the lake, was full of fish whose populations were maintained in various ways. Fishing leaders designated areas to be fished and would not allow unreasonable numbers to be taken. In the spring, suckers and parasitic fish were seined, and female fish were left alone. The Washoes believed the Creator had given them a sacred trust as wards of the region.

Place was of utmost importance to the Washoes. Earl James, a community leader in the 1960s, commented that the lake sustained the Washoes “as a mother, as a provider.” In 2007 Art George Jr., a tribe member who follows traditional Washoe doctrine, commented, “There are many places all the way around Lake Tahoe that are very sacred to us…. This is a center of our spirituality, of our land's spirituality.”

Cave Rock is a 360-foot monolith towering over the east shore. The massif's main cave would seem to have been an ideal homesite for early man, but the Washoes say that from time immemorial it served a different purpose. It was the shamans' sanctum: a place where they might gain or replenish their power. Other humans were forbidden to trespass there; doing so would endanger the individual, the clan, and perhaps the entire tribe. Archaeologists' findings confirm the contention. They have found no vestiges of habitation at Cave Rock. The more esoteric, or mystic, use of the site is implied by the artifacts discovered there, including the oldest objects: three basalt projectile points and an inscribed mammal bone.

In the early twentieth century historian Grace Dangberg recorded several translated Washoe tales. One called “The Weasel Brothers” describes the adventures of two mischievous weasels, Pewetseli and Damalali. The story features a scuffle between Damalali and a Water Baby that begins on the southeast shore of the lake. As they wrestle under-water, they move along the shore, and places are named: “This will be called Mortar Creek. And then they came away from there. People will call this Fish Passage. And then they came away from there. The Washoe will call this Rock Standing Gray (Cave Rock). And then they came away from there.”

In another part of the weasel brothers' story, Nentusu, the Creator, counsels people who are singing, playing games, and making a great noise to be quiet. They ignore her and fall prey to a human-eating giant. Another of the mythological creatures in Washoe lore is Ang, a giant bird that nested on a rock in the lake near Cave Rock. Ang, and other monsters, preyed on humans, and through cautionary tales about them, Washoes learned to be careful and vigilant. Perhaps it is owing to the tales that when the first wave of Euro-Americans arrived in Washoe lands, the newcomers assumed the few individuals they glimpsed were neighboring Paiutes or Miwoks, not realizing a distinct tribe lived in the area.

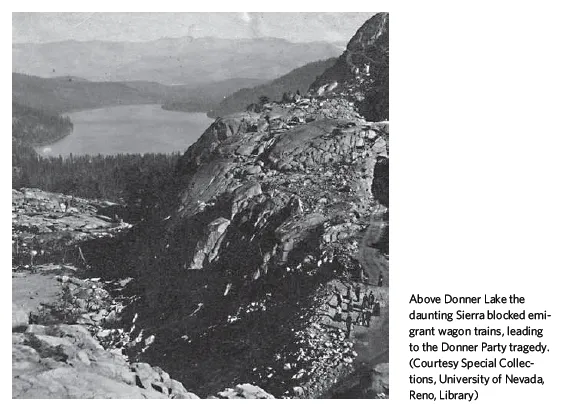

On February 14, 1844, John C. Frémont and members of his exploration party became the first Americans to view Lake Tahoe. They were atop Red Lake Peak on Carson Pass, sixteen miles due south of the lake. In November of that year five wagons of the eleven that composed the Elisha Stevens emigrant train became the first to cross the Sierra. The party followed the Truckee River, originally Frémont's Salmon Trout River, renamed for Chief Truckee—the Paiute Indian who guided the Stevens train. (Truckee was renowned as a leader, and his progeny included his son Chief Winnemucca, for whom the Nevada town is named, and his redoubtable granddaughter Sarah Winnemucca.) The river led to the body of water later named Donner Lake, after the tragic Donner Party that became trapped there. The Stevens group was confronted with the vast, perhaps impenetrable, mountain wall at Donner Pass. With snow on the ground and more threatening, the party split to improve their chances of survival. While the five wagons and their teams succeeded in an epic struggle to gain the pass, six members on horseback followed the Truckee to the south. They reached the river's Tahoe headwaters, becoming the first whites to set foot on the lake's shore. They skirted the northwest side of the lake to McKinney Creek, used the creek valley to gain the mountain crest, and followed tributaries of the American River to John Sutter's fort.

Some four years later John Calhoun “Cock Eye” Johnson, owner of a ranch east of Hangtown, soon renamed Placerville by self-conscious city fathers, found the great natural lake basin while searching for an alternative to the Carson Pass route established by Frémont. In 1852, two years after California went from being part of Mexico to part of the United States, Johnson cleared a rudimentary road between Placerville and Lake Tahoe, known as Johnson's Cut-Off. It followed the approximate route of today's U.S. Highway 50 until entering the Tahoe Basin. There it turned abruptly southeast through what is now called Christmas Valley and crossed Luther Pass, named for Ira Luther, who traveled by way of the pass in 1854 and painted his name on a rock, to meet the original emigrant trail at Hope Valley.

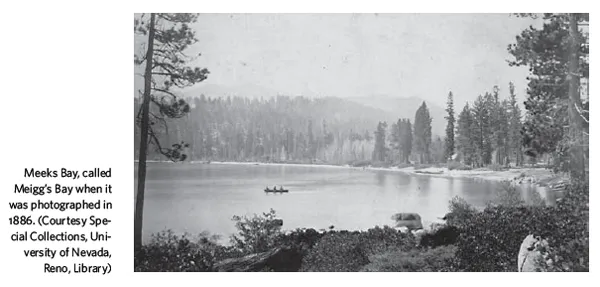

In the summer of 1853 Johnson and a correspondent for the Placerville Herald became the first white men of record to discover Meeks Bay. Washoes were living there, utilizing the lake, meadow, and stream that fed both. Nine miles directly across the lake they saw Cave Rock. Without explaining how they were able to understand the Washoe language, they reported that a centenarian patriarch told an ancient legend concerning the rock and a water prison of demons. The Americans claimed that the tale explained the wailings and pent-up moaning that could be heard increasing in terror and intensity when the waters of the lake rose. The incredibility of the entire episode is demonstrated by the description of the explorers' trip in hollowed-out logs across the lake to the granite massif. The cave, in the middle of the formation, is eighteen feet wide and ten feet high at its mouth and extends horizontally thirty feet to its eight-by-eight-foot back wall. In Johnson's tale it is described as a mysterious grotto two hundred feet high, full of icicles and stalactites.

More accurate descriptions of the area came from George H. Goddard, the surveyor for the California state boundary survey party, who in 1855 described Cave Rock simply as a “Legendary Cave.” His comprehensive report on the lake's environs reads in part, “The surrounding mountains are three and perhaps four thousand feet above the lake, which is deep blue and perfectly fresh. The bases of the high mountain ranges are of white granite sand, forming beautiful beaches, and dense pine forests at other points run from the water's edge to the summit.” He concluded his essay with an apologia: “My poor attempts with pencil can give but a faint idea of the beauty of this spot, and we can only hope to recall to those whose eyes have already beheld the scene what must ever be one of memory's most pleasant pictures.”

Asa H. Hawley was one of the first Americans to settle at the south shore of the lake in the area pioneers called Lake Valley, later named Tahoe Valley. In 1854 he opened a trading post and public house along the Johnson route after he and two associates, the future railroad magnate Collis Huntington and James H. Nevett—later chairman of California's Wagon Road Directors—improved the Johnson roadway. Hawley's dealings with the Washoes at Tahoe were quite different from Johnson's. The Natives would not allow Hawley or other white men to fish in the lake. Hawley, who said he considered all Indians deceitful, said, “They tried to drive me off but I never was afraid of Indians except their treachery.”

In either 1856 or 1857, Hawley, James Green, and John A. “Snowshoe” Thompson rowed a small boat that Hawley built around the lake, becoming the first Americans to navigate it. They were trying to discover if the lake had an outlet, an open question at that time. They discovered the Truckee, although they did not know its name. At one point, with Green rowing close to the shore, Hawley paced a half mile to see how fast they were traveling. They were trying to determine how long it would take them to circumvent the lake. Their primitive calculations lacked precision, and they concluded that Tahoe's circumference was 150 miles, more than twice its actual size.

In 1859 Capt. J. H. Simpson, of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, explored the Great Basin of the Utah Territory, much of which later became the state of Nevada. Coming upon Tahoe, then known as Lake Bigler, after John Bigler, California's twice-elected governor, Simpson described it as “a noble sheet of water … beautifully embosomed in the Sierra.” On June 13 he wrote of a ride he had taken that morning: “Lake Valley is like a beautiful park, studded with large, stately pines. The glades between the trees are beautifully green, and the whole is enlivened by a pure, babbling mountain stream [the Upper Truckee River]…. The pines of various kinds are very large, and attain a height of probably from 100 to 150 feet. Their diameter is not infrequently as much as 8 feet, and they sometimes attain the dimension of 10 feet.”

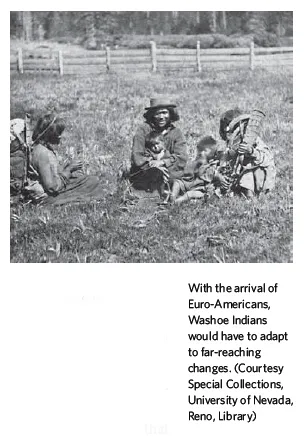

The Lake Tahoe described by the explorers, which generations of Washoes had known, soon changed; barbed wire, clear-cut forests, and tourist resorts became commonplace in the valley. The Americans denied the Indians access to the parts of the lake and its tributaries where fish were abundant. Tourists were catching hundreds of silver trout daily, and commercial fishermen used half-mile-long seines to remove the fish by the ton, until eventually the lake's species was destroyed. As more and more Americans arrived, restrictions became more pronounced. In the last part of the twentieth century, elder Belma Jones commented on the privatization of the land: “We used to swim anywhere, and there weren't any houses, you know, on the beach like now. We used to go from the north shore clear over to what is now that estate there [Valhalla, on the south shore]…. Later people began to fence, so we couldn't go through there anymore.”

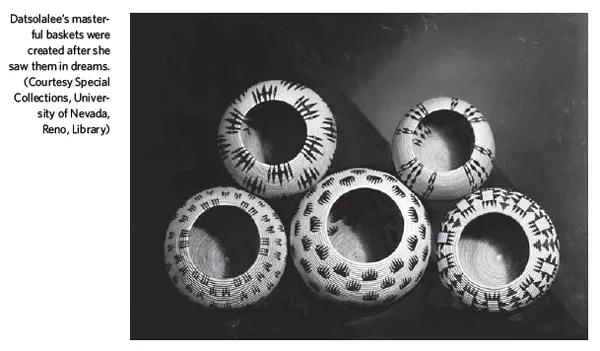

Washoes managed to adapt, returning each summer to the lake, but now they worked as laborers, dairy hands, or domestics, setting up campsites in places no one else had claimed. Some men worked leading pack trips or as fishing and hunting guides; women turned from weaving utilitarian baskets to selling decorative baskets to tourists. The weavers, masters of perspective and symmetry, were among the best in the world. Gaining particular posthumous fame are Datsolalee, known not merely as an artist but as a genius, and her cousin Ceese; although not as prolific, she was thought by early-day collectors to be in every way equal to Datsolalee. The basket makers collected branches and roots from Tahoe's willow, cedar, fir, and pine and cured them for warping strands and dyes. Datsolalee cured some materials for twelve years before using them. She saw baskets in her dreams and then produced them, using fine, even stitching and harmonious colors and designs. One of her most famous baskets, which took two years to make, contains 84,500 tightly woven stitches. Her baskets, as well as those of other Washoes, are now displayed in museums across the country, including the Steinbach Indian Basket Museum attached to the Gatekeeper's Museum at Tahoe City.

To this day the Washoe Indian legacy remains primarily historical at the lake, as the tribe owns no land. In 1998 the tribe won a competitive bid for a special-use permit to operate Meeks Bay Resort and Marina for up to thirty years. Another permit, for the same amount of time, was issued so they might manage a 350-acre meadow near the mouth of Meeks Creek for the care and harvesting of traditional plants. In August 2003 an act signed into law conveyed twenty-four acres on the east shore near Skunk Harbor to the secretary of the interior in trust for Washoe tribal uses. Although gaining access to these pieces of land, and having Washoe displays at D. L. Bliss State Park on the west shore and the Tallac Historic Site on the south, Washoes live primarily on reservations outside the Tahoe Basin. Since they had prospered in the lake's environs over a time span counted in thousands of years, it is apparent that their absence has been injurious to the welfare of both the tribe and the lake.

![]()

Chapter Two

Trails to Roads

James Sisson's lower legs were badly discolored: The gangrene had begun spreading upward from his feet. Unless his legs were amputated, he would die. Snow had trapped him in the Lake Valley cabin that served as a summer trading post between the two high passes on Johnson's Cut-Off. But on December 29, 1856, there were no other humans anywhere in the vicinity. He had baling rope and an ax, and he was contemplating forming tourniquets with the rope and attempting to cut off his legs. Caught by a blizzard, his boots had frozen to his frostbitten feet. He suffered through four days at the cabin without a fire. When he finally found matches under some scattered straw, he thawed the boots enough to remove them. Now, another eight days had passed, and Sisson dragged himself about, subsisting on raw flour left at the post.

Snowshoe Thompson, arguably the greatest mountaineer in Sierra history, had just begun a mail service that would last twenty years. He was crossing the mountains alone, carrying the mail on his back. Using oak slabs, he had fashioned ten-foot, twenty-five-pound skis after those he remembered from his early childhood in Norway. The trek from Placerville to Carson Valley and back consisted of 180 miles up and over the snow-filled mountains. On that December night he paused at the trading post and found Sisson. Thompson left the injured man, skiing through the night over Luther Pass to the nearest settlement, Genoa, Nevada. He recruited six men and guided the party back to the trading post.

They built a hand sled to carry the victim, but the travel was brutal. Snow had continued, adding two feet to the eight-foot snowpack, and only Thompson had much experience on skis. The sled, under Sisson's weight, sank, at times becoming buried almost out of sight. It took two days to get Sisson out of the mountains. In the valley they took him to the territory's only doctor, C. D. Daggett, who lived at the base of a mountain grade called Daggett Pass. The doctor knew he would have to amputate but needed chloroform. Thompson, without sleep, started out again, crossing the mountains to Sacramento and returning to Genoa some days later. Dr. Daggett performed the long-delayed operation, allowing Sisson to live many more years. Thompson carried the mail over the mountains every winter until 1876. For those twenty years, when the Sierra roads were buried in snow, he provided the only mail service between California and the East.

The harshness of the winters and the absence of developed roads caused other heartrending incidents. The most famous, the Donner Party episode, occurred in 1846. Stranded at the lake that now bears its name, a number of the party cannibalized others who died from starvation and the elements. Although recently contested, distinguished Sierra historians George Hinkle and Bliss Hinkle wrote, “[Donner Party leader James F.] Reed himself, although he avoided mentioning names, left no doubt that there had been cannibalism.”

Two years earlier, at the same spot, Moses Schallenberger, a twenty-year-old from the Elisha Stevens emigrant train, remained with two older men to guard wagons that had to be left behind. When storm followed violent storm and provisions dwindled, the men made makeshift snowshoes out of wagon bows and rawhide and started out. The older men fought their way over the pass and down into California; Schallenberger's strength gave out, and he was forced to return to the makeshift cabin they had built. He suffered through a miserable two months until help arrived, s...