eBook - ePub

Building Hoover Dam

An Oral History Of The Great Depression

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Andrew J. Dunar and Dennis McBride skillfully interweave eyewitness accounts of the building of Hoover Dam. These stories create the richest existing portrait of the building of Hoover Dam and its tremendous effect on the lives of those involved in its creation: the gritty, sometimes grisly realities of living in cardboard boxes and tents during several of the hottest Southern Nevada summers on record; the fearsome carbon monoxide deaths of tunnel builders who, it was claimed, had died of "pneumonia"; the uproarious life of nearby Las Vegas versus the tightly controlled existence of the workers in the built-overnight confines of Boulder City; and of course the astounding accomplishment of building the Dam itself and completing the task not only early but under budget!

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building Hoover Dam by Andrew J. Dunar,Dennis Mcbride in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INVESTIGATION AND APPROVAL: SOUTHERN NEVADA, 1902–1929

“Incomprehensible how they could build a dam there.”

For decades before construction of Hoover Dam began, the federal government had wanted to build a dam on the lower Colorado River. After devastating floods in California’s Imperial Valley in 1905–07 stirred demand for flood control, the Bureau of Reclamation investigated potential damsites along the river near Las Vegas, Nevada. Reclamation engineer Walker R. Young led investigations during the early 1920s in Boulder and Black canyons. Later he became the chief construction engineer during the building of Hoover Dam.

WALKER R. YOUNG

The Colorado River had been under study for many years—you might say from the inception of the Bureau of Reclamation in 1902. Mr. [Joseph Barlow] Lippincott in 1905 was sent to get a look at the lower part of the river. Nothing was done at that time, but later they got to thinking about irrigation, flood control, demands for power, domestic water supply. Dr. Arthur P. Davis, who was then the commissioner of Reclamation, got the idea that a large storage should be provided for the lower Colorado River near the point of use. So he originated the idea. I consider him the father of the Boulder Canyon Project.

Then Homer [Hamlin], who was a geologist [for] the Bureau of Reclamation, was sent down to explore the river below the entrance of the Virgin River. He and an assistant, whose name I believe was Wheeler, made a trip down the river as far as Blythe [California]. He was looking for a damsite that would provide for an immense storage. He reported that there was a damsite available in Boulder Canyon, depending on the results of an investigation, that would meet the requirements. He said that if for any reason it should develop after an investigation that the damsites in Boulder Canyon were not suitable, there was another site 20 miles downstream in Black Canyon.

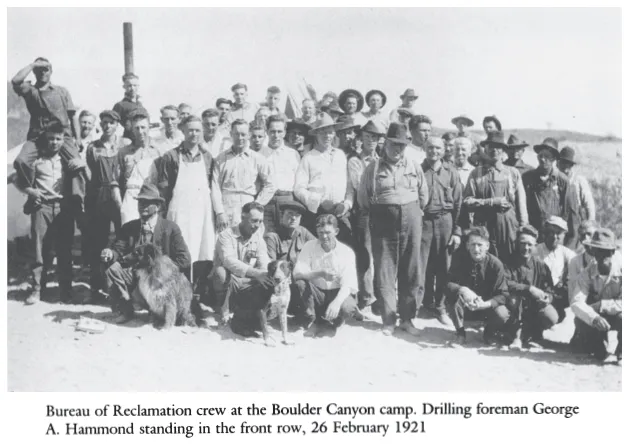

Mr. Davis, the commissioner, and Frank E. Weymouth, who was then chief engineer in the Bureau of Reclamation office in Denver, Colorado, made a trip down the river personally [in November 1920]. They came back to Denver. At the time I happened to be working in the chief engineer’s office. They asked me how soon I could leave for Boulder Canyon. So I started out with Mr. James Munn, who was the superintendent of construction for the Bureau of Reclamation, a man that I had worked with at the Arrow Rock Dam. He was sort of a father of mine. He and I arrived at St. Thomas, Nevada, in the last week of December [1920]. We went down to look over the canyon and came back with the idea that the work should be speeded up, and so reported. I had some experience before this in the investigation of damsites and working at damsites. I became in charge of the investigation. That was Boulder Canyon, the one that was first suggested for Hoover Dam.

Young and his crew established a camp at the entrance to Boulder Canyon, 50 miles from Las Vegas. For two years they conducted investigations and reconnaissance of the river from Boulder Canyon to Black Canyon, 20 miles to the south. Edna Jackson Ferguson’s husband, Clarence, was a member of this Reclamation crew.

EDNA JACKSON FERGUSON

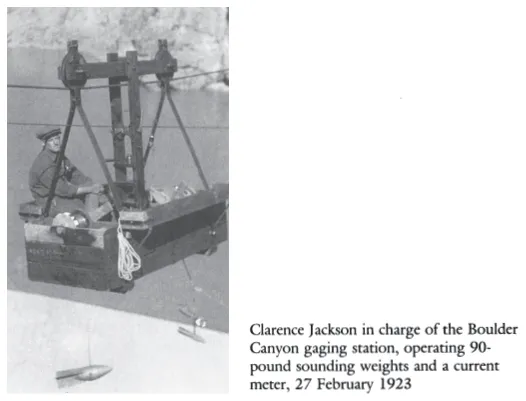

It was the latter part of December 1922. Clarence Jackson, known to most people as Jack, had just finished a job in Utah and was returning to Los Angeles to seek more employment. Stopping in Las Vegas overnight, he decided to try his luck at finding work on the big dam that was going to be built on the Colorado River. The Bureau of Reclamation had offices in Las Vegas directing the preliminary investigations into the building of the dam. The man in charge was Walker R. Young. After a short interview Jack was hired.

Investigations were being made at both Black Canyon and Boulder Canyon to see which place would be more suitable for such a giant piece of construction. Jack was told to report for work at the camp for field employees at Boulder Canyon. It was approximately 50 miles from Las Vegas.

To reach this camp, one traveled the main highway towards Salt Lake City for a few miles, then turned to the right on a road used and maintained by a large borax mine. This dirt and sometimes gravel road was followed for about two-thirds of the distance. Then for 17 miles to go to Boulder Canyon, one followed dry washes over hills and the tracks and ruts of those who had been this way before. Anyone familiar with flash floods can understand how the tracks and ruts that they had followed going into town could be washed out on the return trip. Only an experienced eye could pick out the correct way to go. The road, if one can call it that, was so narrow in places that sometimes in making a turn one had to make a complete circle, crossing their own tracks to negotiate the turn and be able to get started up the road ahead. All the supplies had to be brought from Las Vegas over this route.

When Jack arrived at camp, he found it well organized with a field office, mess hall, sleeping quarters for everyone, and the necessary equipment to take care of about 30 men. There were no buildings. Only tents were used. The investigations had been going on for several years, but because of the intense heat in the summer months the field work had only been done when it was cooler—I would say from early fall to mid-March.

My husband was given the responsibility of measuring the flow of the water in Boulder Canyon—that is, how many cubic feet of water was rushing through the canyon. This information was necessary in the planning of the dam because of the strength that would be needed to curb the flow of water. Besides taking the flow of the water, surveyors were mapping the terrain, and geologists were measuring and studying the formations of the earth structures.

Boulder Canyon was a beautiful place. The camp itself was situated probably one-fourth to one-half mile from it. At camp large willow trees lined the riverbank, and there was plenty of desert vegetation to make it attractive. Boulder Canyon Gorge was very narrow, and the hills of solid rock towered so high on either side that one could scarcely see the tops.

In March [1923], with most of the work at hand completed, the camp was broken up and the men went their separate ways to compute their findings or to other projects. Only a skeleton camp remained, with my husband and an assistant remaining to carry on their work.

After camp had broken up in March, every day Jack and his helper would walk the distance from camp to the place where they took their measurements. At this point was a heavy cable across the river. Attached to this cable was a mobile tram, and they would climb [in] with their instruments. Of course, the weight of the car made the cable sag in the middle. They would coast to this point, then by hand pull themselves up to the far side. From there they came back slowly, dropping their meters, which were attached by wires to the tram into the water below. One of the meters measured the rate of flow of the water; the other, the depth of the river. The meters would be drawn up, read, and let down a little further on. This process continued until they were back at the point from which they started with the tram. On the return trip, again when they reached the middle of the stream, it was uphill the rest of the way. They had to crank the machine pulley as well as take the readings. When reaching the place from which they had started, the tram was secured, and back to camp they went to compute and record their figures.

Jack and I were married in Las Vegas May 17, 1923. I had been teaching school in Idaho, and the snow was barely gone from the ground when I left there to find two days later a temperature of a hundred four degrees. It was in this heat we traveled to Boulder Canyon, our first home. Our camp was near the river at the mouth of a wide wash. We had an office tent, which doubled as the helper’s living quarters; a kitchen–dining room tent; and our living quarters tent, which stood on a knoll near the cooking tent so that it could catch the cool breezes when and if. Later the boys put up a small tent with a steel drum rigged up over it for a shower tent. Water was pumped into the drum, and the sun warmed the water. Sometimes it would be too hot to use. Who knows—this may have been the original solar heating system. For our drinking water there were several barrels which were pumped full of water from the river. It would take a day at least for the silt to settle before we could use the water.

One might wonder how food was kept from spoiling in this climate. A cave, approximately five feet square, had been dug into the side of the hill near the mess tent and timbered up inside to keep it from collapsing. The front was walled up and was about a foot thick. There were two doors leading into it. The first one was an ordinary door. The inner one was about six inches thick, made so it was insulated so that no heat could get through it. When the groceries were brought, there was always a 300-pound cake of ice. The ice went in first, and all perishables were placed on and around it. One had to be very careful not to leave the doors ajar when entering so as little as possible heat could get through. A flashlight or lantern had to be used as there was no light in there.

I had the opportunity to go down through this big canyon in a boat that was piloted by an expert who knew the river well,1 where the rocks and eddies were. It was an awesome sight. At the time they said I was the first woman to go through there, and that very few men had made this trip. Since then only a few expeditions were made before it was inundated by the waters of Lake Mead.

I claim the distinction of being the first white woman to have lived in this area, and I doubt that there were many after me. Now all this territory is covered by Lake Mead. We lived there until December [1923], the last few months of which my husband had no helper, so I helped with the book work and reports required for information at the office in Denver. When we left, everything was dismantled as that was the end of the investigation in Boulder Canyon.

WALKER YOUNG

We had to build new barges, build new drills, build new boats to take the crew back and forth in this river. The result of that work was that we drilled three damsites in Boulder Canyon. After we got the information from Boulder Canyon, we thought of Homer Hamlin’s suggestion of a damsite about 20 miles below [in Black Canyon]. So I went with George Hammond, a man of 60 or 65 years old who was the drill foreman, and Harry Armisted, an old experienced riverman, and his dog Baldy. We three got in a boat that he [Armisted] had built. It was a small one because we knew we had a job getting back upstream. It was a 16-foot boat. George Hammond was a fellow that weighed about 200 pounds. Harry Armisted was not that heavy, but he was an oarsman. All he did was sit and row. We sized [Black] Canyon up on a preliminary basis. When we were there, we discovered a stake that was set by Homer Hamlin several years before. It looked to us that the lower canyon suggested by Homer Hamlin was the best in that site. We recorded that and started back. We almost didn’t get back, because the river at that time was running fairly well with those sand waves. You remember from studying the Colorado River what sand waves are. It simply means that the velocity of the water reached the point where it picked up the sand from the bed of the river and made it roll. It would break like ocean waves. When we went down in the trough of one of those waves, we’d get full of sand.

There is some explanation of why the change was made in the location of the dam in Black Canyon rather than Boulder Canyon. As I recall, we discovered that the upper end of Boulder Canyon would be right in the vicinity of a fault. Also, because of this great big storage capacity in the Las Vegas Wash basin itself between the two sites, it turned out it was less expensive to build a dam in Black Canyon rather than Boulder Canyon. At Boulder Canyon there were no locations for a spillway. The thing that turned the tide over was the fact that one day when I was trying to find out whether we could reach the damsite from the top—we’d already reached it from the bottom—I discovered it was [possible] to actually build a railroad from the main line [in] Las Vegas to the top of the damsite. I mean right at the top. There was considerable relief on the part of the chief engineer and his crew when we found we could get the resources, millions of tons of materials, down to that damsite on a standard gauge railroad. As I’ve said many times, the Lord left that damsite there. It was only up to man to discover it and to use it.

Until the Bureau of Reclamation determined when it would build Hoover Dam, the Colorado River near Las Vegas was home to hard-rock miners, beaver trappers, and rivermen. One of the earliest of these river rats and the best known was Murl Emery, who had lived with his family on the river since about 1917. It was Murl Emery who ferried Walker Young and other dignitaries up and down the river throughout the 1920s.

MURL EMERY

We homesteaded on the Colorado River at Cottonwood Island. The first move was to keep the wolf from the door. We leased Jim Cashman’s old ferry that was tied up on the bank on the Nevada side at Cottonwood Island. We had a boat down there, and a marina there many years later. I became the ferryman, because Dad had come to the point that the grass was greener over in Lordsburg, New Mexico. So he took off and left us on the homestead.

I was running the ferry at about 14 years old. So I developed the ability of navigating on the Colorado River. No rapids, just muddy water. It was awfully hard to find clear water to run the boat in. I became the expert at it as time went along. I had to know what I was doing, because I could get the ferry to Arizona and back to Nevada.

Another highlight in my life was when the beaver trappers came down the river. What they would do—about Christmastime each year they would wind up in St. Thomas, Nevada. They would come in there, make a deal with somebody to load up their gear, and go by wagon down the Virgin River to Rioville. Part of their load, outside of the necessary bacon and beans, their lard and whatnot—the load consisted of two-by-fours, one-by-twelves, a bucket of tar, and a handful of nails. They’d just build themselves a little flatbottom boat and make a pair of oars. And that’s what they used coming down the river.

I would get word that they were trapping up on a foot trail, or one of these places between Black Canyon and Cottonwood. Once they came down into this area, I had to come home and run the ferry because the beaver trappers were my heroes. They were the world’s best. I learned to trap from them. Of course, the most important thing on my mind was food. I would go camp with them, and they would feed me. They would eat—serve beaver, of course. You have to develop a like for that because the like isn’t built in.

The reason they came down here was the fact that the Colorado River had the finest beaver in the United States or Canada. Big beaver, minimum dark hairs, so that made it choice. Our beaver pelts was shipped to St. Louis at that time. It was superfine, and I’d get as much as $40 a blanket. As long as we had the beaver, I had no more hard times, because they were good money.

The most important thing that I learned from this ferry operation was the fact that the Volstead Act was in effect at that time. That meant one thing: whiskey was the deal. These bootleggers would come out of Nevada down to the ferry, pretty well out in the open, hollering it out, “Anybody on the other side?” T...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Investigation and Approval: Southern Nevada, 1902–1929

- 2. Settlements: Black Canyon and Vicinity, 1929–1931

- 3. Construction Camp: Boulder City, 1931

- 4. Turning the River: Black Canyon, 1931 to November 1932

- 5. A Government Reservation: Boulder City, 1932–1934

- 6. Laying the Foundation: Black Canyon, 1932–1934

- 7. A Day in the Life: 1931–1935

- 8. Off the Reservation: Las Vegas, 1931–1935

- 9. Towers, Penstocks, and Spillways: Black Canyon, 1934

- 10. Completion: Hoover Dam and Boulder City, 1935 and After

- Conclusion

- Appendixes

- Notes and References

- Index

- The Authors