![]()

Chapter One

From Camping Grounds to Towns

During the past three hundred million years, the Denver metropolitan area has been under water and above water, higher and lower than it is now, warmer and colder. It has been home to dinosaurs and mammoths, bison, elk, antelope, and an ark full of other species, including humans. It has witnessed mountains rise and fall, with the current Rockies coming into their glory after crustal upheavals that began some sixty-seven million years ago.

Over the eons, debris deposited by swamps, seas, and eroding mountains created thousands of feet of sedimentary rock now buried under the city. Near the base of the mountains, subterranean forces tilted those layers upward to create hogbacks and sandstone formations such as the Dakota Hogback, where footprints of three-toed dinosaurs may be seen. Crustal movements also thrust up the jutting slabs in Red Rocks, Roxborough Park, and the Flatirons. Among these monoliths, archaeologists have found the area’s oldest homes—rock shelters. Archaic era (5500 BCE–0) peoples built these residences tucked into the nooks and crannies of rock. They left behind the stone tools used to kill and butcher game. Bone hooks and net sinkers show they fished. Spear throwers and projectile points prove they hunted. Even earlier, between 10,000 and 8000 BCE, Clovis and Folsom peoples traversed the base of the mountains.

Native Americans favored the region because of its fortunate location, with access to the plains and the mountains. Lying in a trough along the eastern base of the Front Range, a subdivision of the Southern Rockies, Denver’s site is more sheltered than the high plains to the east and often cooler in summer and warmer in winter than higher land to the west, east, and south. The city’s main waterway, the South Platte River, tumbles out of the mountains through picturesque Waterton Canyon, about twenty-five miles south of downtown. Captured and channeled by the trough, the river flows through southern suburbs, including Littleton and Englewood, and into the heart of the city, where it meets Cherry Creek, which drains high land to the southeast. North of the city limits, the South Platte intersects other streams, such as Clear and Ralston Creeks, which contribute mountain water. Then the river slants northeastward on its way to irrigate farms in northeastern Colorado. In Nebraska it joins the North Platte to form the Platte, a tributary of the Missouri River, which in turn empties into the Mississippi. Along those watercourses Native Americans found water, shade, and in the winter sheltered camping sites. When warmer weather arrived, they spread out onto the plains to pursue bison and in high summer followed the animals into vast mountain valleys, such as South, Middle, and North Parks.

For centuries, the first beneficiaries of the area’s favored location enjoyed much of what they wanted and needed. They were only sporadically bothered by Spanish and French claimants to what became Colorado because neither France nor Spain effectively occupied the area. What the Indians did not have, a piece of parchment sealed with blobs of red wax, foreshadowed their undoing. That document, the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, gave the United States a claim to the land. France got fifteen million dollars, and the United States got more than 800,000 square miles, mostly made up of the western drainage basin of the Mississippi River. For the 153 square miles that today constitute the City and County of Denver, a flyspeck on the huge map of Louisiana, the United States paid less than three thousand dollars. The French left behind a few place-names, including Platte, which means “flat.”

Arapaho and Cheyenne

The Southern Arapaho (Hinono’eino) and Southern Cheyenne (Tsitsistas), allied tribes that in 1800 occupied the northeastern part of what would one day be called Colorado, initially had little reason to worry about a real estate deal made in Paris. Except for a few traders and trappers, Euro-Americans were not interested in the dry plains north of the Arkansas River, tracts that many, including US explorer Stephen H. Long, who visited the area in 1820, considered a desert. To eastern and midwestern farmers, the Platte River country seemed nearly worthless and hence a good place for Indians. At times the Arapaho camped along Cherry Creek, near its junction with the South Platte River, naming the creek for the wild chokecherries they harvested along its banks. Their fondness for that waterway led St. Louis fur trader Auguste P. Chouteau in 1815 to host a trading camp there, where he bartered with the Indians for buffalo robes, beaver pelts, and wild horses.

The name Arapaho may have come from the Pawnee word for “buyer” or “trader.” They called themselves “bison path people” or “our people.” Others referred to them as the “Tattooed People,” because they scratched their breasts with a yucca-leaf needle and then rubbed wood ashes into the wound to make an indelible mark. They arrived in Colorado around 1800, pushed from their Great Lakes homelands by other tribes. After crossing the Missouri River, the Arapaho split. The northern branch headed for what would become Wyoming, the southern offshoot for Colorado. As they lapped against the eastern edge of the Southern Rockies, they met resistance from the Ute. Consequently, the Arapaho lodged at the base of the Front Range, with as many as fifteen hundred camping on the future site of Denver in the 1840s and 1850s.

The Cheyenne, as historian Elliot West tells in The Contested Plains: Indians, Goldseekers, and the Rush to Colorado (1998), also left their ancestral homes. Obtaining horses, they became superb riders and expert bison hunters. For them and for the Arapaho, bison were the animal equivalent of gold—the mother lode that undergirded their economies and shaped their societies. In 1851, by terms of the Treaty of Fort Laramie, the United States promised both tribes that they could continue hunting between the Arkansas and North Platte Rivers. Just seven years later, in 1858, the promise crumbled when newcomers discovered the metallic gold they craved in the sands of the South Platte.

Gold and Wars, 1858–1869

The forces that gave the Native Americans a pleasant home also created conditions that, coupled with other factors such as disease and the decline of the bison herds, hastened the Indians’ demise. Less than forty miles west of Denver are Front Range mountains interlaced in a few places with a heavy yellow metal savagely coveted by Euro-Americans willing to risk their own lives and kill others to get it. Millions of years of erosion scattered grains of that gold at the base of the Rockies, where in midsummer 1858 prospectors recovered some of it from South Platte placer deposits. News of those strikes raced eastward, prompting hundreds of gold seekers (sometimes called Argonauts, in reference to the tale from Greek mythology of Jason and his Argonauts, who sought the Golden Fleece in a ship named Argo).

In 1859 the Argonaut trickle turned into a flood. Pursuing their dreams of securing a good living, some of them hoped to add to their wealth. Others came out of desperation born of an economic depression that began in the late 1850s. Part of a long-term westward movement, many considered it their destiny to occupy the continent. In some ways, the newcomers, most of them young men, were similar to the Native Americans. Both were pushed and pulled by economic forces. The differences were also obvious. The Euro-Americans, unlike most of the Indians, wanted to mine, ranch, and farm; to construct railroads; and to make cities. In their world there was little, if any, room or hope for the bison or for the Native Americans.

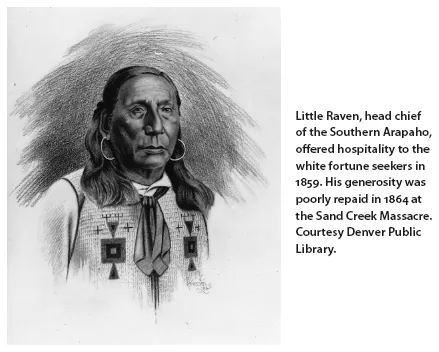

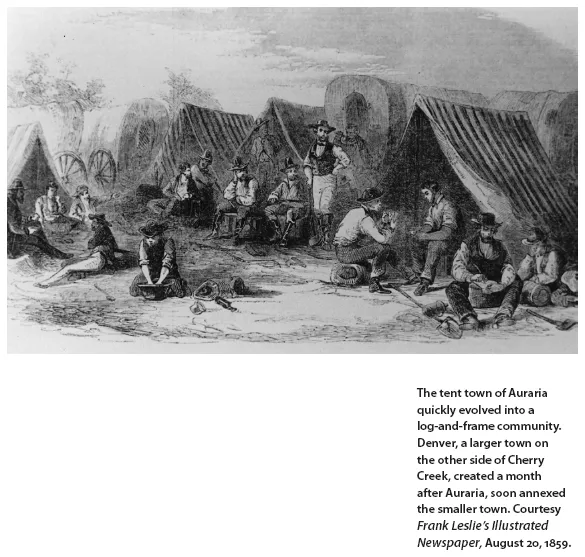

At first, the Tattooed People, who had traded with whites for decades and whose daughters had sometimes married Euro-American fur traders, welcomed the “spider people,” the name the Arapaho gave the whites. Chief Little Raven entertained them in his handsomely decorated teepee and visited with them in their log cabins. Arapaho friendliness is demonstrated by the saga of the Blue brothers, Alexander, Daniel, and Charles. The Blues ran out of food as they journeyed west in the spring of 1859. After Alexander and Charles died, Daniel survived by eating their remains. He too might have starved had it not been for an Arapaho who found him, fed him, and brought him to Denver, where townsfolk scraped together enough money to send him back to Illinois. Unlike the Blues, most pilgrims arrived safely at Auraria and Denver, the towns that sprouted in the autumn of 1858 along Cherry Creek, near its confluence with the South Platte. By the spring of 1859, the Arapaho and Cheyenne had been swamped by energetic, well-armed aliens, many of whom regarded Indians as degraded people.

Many of the interlopers, finding little gold, quickly gave up and, like Daniel Blue, went home. Others followed the lure of gold into the mountains. Unfortunately for the Indians, a few thousand whites recognized that they could make money in the supply towns at the base of the mountains. By 1860 around five thousand people were ensconced in Denver and Auraria on land the Treaty of Fort Laramie had promised to the Cheyenne and the Arapaho. To provide legal cover for their citizens’ land grab, the US government in the fall of 1860 invited the Cheyenne and Arapaho to meet with federal agents, including Albert Gallatin Boone, grandson of frontiersman Daniel Boone, at Fort Wise (later renamed Fort Lyon), on the Arkansas River, more than 160 miles southeast of Denver. Negotiations dragged on for months. Finally, early in 1861, ten Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs, including Little Raven, signed the Treaty of Fort Wise. Other tribesmen objected. George Bird Grinnell in his The Fighting Cheyennes (1956) recounts that some Arapaho complained that “they had not been present [at the treaty signing] and had received nothing for their ‘land and their gold.’” Little Raven, Grinnell reports, remembered, “The Cheyennes signed [the Treaty of Fort Wise] first, then I; but we did not know what it was. That is one reason why I want an interpreter, so I can know what I sign.” Whites, on the other hand, liked the treaty because it erased the claims of the Native Americans to most of northeastern Colorado, including the Denver area.

Losing land was bad enough, but the two tribes’ problems ran even deeper. For more than a decade, the bison herds upon which they had depended had been declining. The Indians’ huge horse herds overgrazed the grasslands, and Euro-American migrations to Utah, Washington, Oregon, and California further stressed the plains ecosystem. By the early 1860s, many of the Indians were starving and sometimes raided ranches on the plains looking for food. In June 1864, four young Arapaho killed Nathan Hungate; his wife, Ellen; and their two young daughters on a ranch near Elizabeth, 25 miles southeast of Denver. People gaped at the Hungates’ bullet-riddled bodies paraded naked through town in an ox wagon, vowed vengeance, and grew fearful. In July, seeing a cloud of dust south of town, citizens convinced themselves that Indians were about to attack. Women and children fled to stout brick buildings, where they remained until scouts reported that the dust had been stirred up by peaceful freighters.

Colorado’s territorial governor John Evans capitalized on the Hungates’ deaths to convince the federal government to pay volunteer troops to control the Native Americans. Peace chiefs, including Black Kettle of the Cheyenne, risked their lives by coming to hostile Denver in mid-September 1864 to meet with Evans and Colonel John Milton Chivington, the district military commander, at Camp Weld, a mile south of town near the intersection of today’s West Eighth Avenue and Vallejo Street. Evans weaseled out of the conversation by saying that he was not a military authority. Chivington also parsed his words. While saying that he was “not a big war chief,” he also declared that all the soldiers in the region were under his command. He indicated that as long as Black Kettle and his people maintained good relations with Major Edward W. Wynkoop at Fort Lyon on the Arkansas River, there would not be war. Black Kettle returned to Fort Lyon, where he and other Cheyenne and Arapaho stayed until Wynkoop was removed from command and a new post commander told the Indians to leave. They went north to camp on Sand Creek. There Chivington mounted a sneak attack at dawn on November 29, 1864. Despite the Indians’ attempts to signal that they were peaceful, soldiers continued to fire. By day’s end at least 163 Indians, mostly Cheyenne, many of them women and children, had been slaughtered. Souvenir-hunting troops hacked off parts of the Indians’ bodies as trophies.

The US House of Representatives’ Committee on the Conduct of the War concluded in 1865 that Chivington had committed a “foul and dastardly massacre.” In Denver, where an army board took testimony, many people sided with Chivington. One who did not, Captain Silas Soule, who had refused to participate in the bloodbath, courageously testified against the colonel. For that the captain was killed by an assassin who got away. In Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Dee Brown quotes Little Raven’s lament: “That fool band of soldiers cleared out our lodges, and killed our women and children . . . at Sand Creek. . . . Left Hand, White Antelope and many chiefs lie there, and our horses were taken from us there. . . . Our friends are buried there, and we hate to leave these grounds.”

In reprisal for Sand Creek, some Native Americans raided plains settlements and attacked wagon trains in 1865, but Little Raven and Black Kettle kept pressing for peace. Treaties in 1865 (Little Arkansas) and 1868 (Medicine Lodge) and the 1869 battle of Summit Springs in northeastern Colorado led to the removal of the Cheyenne and Arapaho from Colorado. Many were banished to Indian Territory, which later became Oklahoma. Black Kettle was killed there in 1869 at the Washita Massacre, and Little Raven died a natural death there in 1889. Later, some of the Southern Cheyenne joined their kin in Wyoming. In an 1884 interview preserved at the University of California’s Bancroft Library, John Evans argued, “The benefit to Colorado of that massacre, as they call it, was very great for it ridded the plains of the indians [sic].” His view reflected his and most other Euro-Americans’ conviction that clearing the region of Indians was necessary for Denver’s survival. It also mirrored his bank account. He and other empire builders snatched up land that had belonged to the Arapaho and Cheyenne and pocketed the profits as the city grew. A little more than 150 years after the massacre, Colorado governor John Hickenlooper Jr. formally apologized.

Town Founding

Hickenlooper’s apology did not change the map. To the victors belonged the spoils—much of Colorado, including Denver. It was a city, like many others, founded by those who hoped to make a better life for themselves, perhaps even to get rich. What better to attract wealth seekers than gold? Reports of glittering riches had floated out of the Rockies and the Southwest for centuries. On June 22, 1850, Cherokee Indians on their way to California’s goldfields made a well-documented gold find on Ralston’s Creek, near Fifty-Sixth Avenue and Fenton Street in present-day Arvada, but the small strike did not cause them to tarry. Seven years later, Hispanic prospectors panned in the South Platte River, near what is today Florida Avenue, and in the same year a small party of Missourians said they had found gold in the area.

But it was not until 1858 that reports proved alluring enough to trigger a massive gold rush. That summer William Greeneberry “Green” Russell, a seasoned gold seeker from Georgia, led a party of prospectors, including his brothers, Levi and Joseph, to the South Platte River in western Kansas Territory. There in mid-July they found a respectable placer deposit, gold flakes mixed with river sand, where Little Dry Creek enters the river near Dartmouth Avenue and Santa Fe Drive in present-day Englewood. A few weeks later, another group from Lawrence, Kansas, panned more South Platte gold from near the Russells’ site. Together the finds probably amounted to less than 150 ounces, but from modest discoveries great hopes blossomed. As news of the finds, accompanied by goose quills packed with gold dust, spread east, other gamblers risked their lives by trekking more than six hundred miles from eastern Kansas and Nebraska to what they called Pikes Peak country, imprecisely named for the mountain seventy miles to the south of the South Platte discoveries.

Auraria

The fortune seekers hoped to find gold, but some also banked on cashing in on gold fever by grabbing land, founding towns, and selling lots. With a keen eye for prime real estate, the Russell party established their town, Auraria, on the southwestern side of Cherry Creek, near its juncture with the South Platte. Auraria borrowed its name from the Russells’ hometown in northern Georgia. There in the early 1830s the most important gold strikes in the eastern United States had catalyzed Georgians into driving many of the Cherokee Indians out of that region. The list of stockholders in the Auraria Town Company dated November 1, 1858, included Joseph and William Greeneberry Russell, both of whom had scampered back to the warmer East, telling golden tales as they traveled. Remaining Aurarians, not sure what a winter at the base of snowcapped mountains might bring, set to work building log cabins chinked with mud.

Heading the Auraria stockholders’ list was William McGaa, a trader and trapper whom the founders courted because he had several Indian wives and hence could provide cover for their taking Indian land. They named a street for McGaa, a fleeting tribute that by the late 1860s had been changed by officials who no longer needed McGaa and who considered a polygamist with a fondness for whiskey unfit to associate with less pickled citizens, some of whom, although they approved of defrauding Native Americans, attended church on Sunday. For decades, similarly minded people refused to count McGaa’s son, William Denver, born in March 1859, as the first baby born in the Cherry Creek settlements. They preferred to give the honor to Auraria Humbell, born in July in Auraria, or to John Denver Stout, born in August in Denver. Both of them, as far as anyone knew, had properly wed, monogamous non-Indian parents. A couple of months before McGaa joined the Auraria Town Company, he and a few others had staked out a town venture on the northeastern side of Cherry Creek, near Fifteenth and Blake Streets, a better location than Auraria because much of it was on higher ground and near an ...