- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

From the girl in Red Cloud who oversaw the construction of a miniature town called Sandy Point in her backyard, to the New Woman on a bicycle, celebrating art and castigating political abuse in Lincoln newspapers, to the aspiring novelist in New York City, committed to creation and career, Daryl W. Palmer's groundbreaking literary biography offers a provocative new look at Willa Cather's evolution as a writer.

Willa Cather has long been admired for O Pioneers! (1913), Song of the Lark (1915), and My Ántonia (1918)—the "prairie novels" about the lives of early Nebraska pioneers that launched her career. Thanks in part to these masterpieces, she is often viewed as a representative of pioneer life on the Great Plains, a controversial innovator in American modernism, and a compelling figure in the literary history of LGBTQ America. A century later, scholars acknowledge Cather's place in the canon of American literature and continue to explore her relationship with the West.

Drawing on original archival research and paying unprecedented attention to Cather's early short stories, Palmer demonstrates that the relationship with Nebraska in the years leading up to O Pioneers! is more dynamic than critics and scholars thought. Readers will encounter a surprisingly bold young author whose youth in Nebraska served as a kind of laboratory for her future writing career. Becoming Willa Cather changes the way we think about Cather, a brilliant and ambitious author who embraced experimentation in life and art, intent on reimagining the American West.

Willa Cather has long been admired for O Pioneers! (1913), Song of the Lark (1915), and My Ántonia (1918)—the "prairie novels" about the lives of early Nebraska pioneers that launched her career. Thanks in part to these masterpieces, she is often viewed as a representative of pioneer life on the Great Plains, a controversial innovator in American modernism, and a compelling figure in the literary history of LGBTQ America. A century later, scholars acknowledge Cather's place in the canon of American literature and continue to explore her relationship with the West.

Drawing on original archival research and paying unprecedented attention to Cather's early short stories, Palmer demonstrates that the relationship with Nebraska in the years leading up to O Pioneers! is more dynamic than critics and scholars thought. Readers will encounter a surprisingly bold young author whose youth in Nebraska served as a kind of laboratory for her future writing career. Becoming Willa Cather changes the way we think about Cather, a brilliant and ambitious author who embraced experimentation in life and art, intent on reimagining the American West.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Becoming Willa Cather by Daryl W. Palmer in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781948908283Subtopic

Literary BiographiesChapter 1.

Red Cloud and the “Real West”:

Mapping Willa Cather’s Territorial Imagination

Farm life in that territory when I knew it fifteen years ago was bad enough, what must it have been before?

—Willa Cather

The West is a young empire of mind, and power, and wealth, and free institutions, rushing up to a giant manhood, with a rapidity and a power never before witnessed below the sun. And if she carries with her the elements of her preservation, the experiment will be glorious.

—Lyman Beecher, A Plea for the Nation

A pioneer should have imagination, should be able to enjoy the idea of things more than the things themselves.

—Willa Cather, O Pioneers!

In 1923, Willa Cather’s cyclical existence was palpable and complicated.1 On the one hand, she was enjoying unprecedented success. April Twilights and Other Poems, an impressive revision and expansion of the 1903 volume, was published by Knopf and dedicated to her father. The author had never been prouder than when she finished One of Ours, and the novel was proving quite popular, especially among veterans of World War I. On the other hand, she was unsettled by certain harsh reviews of the book. She had received news of the Pulitzer Prize while in France, unable to write because of neuritis. No one needed to remind her that she was turning fifty. It was in a darkening mood that Cather wrote “Nebraska: The End of the First Cycle.” Appearing in the Nation on September 5, 1923, the author’s only sustained history of Nebraska can be read, at this distance, like an elegy.

It is, in fact, far more valuable as a study of becoming, both territorial and authorial. Using the essay as a guide, we will (echoing Huck Finn at the end of the famous novel) light out for the Kansas-Nebraska Territory that preceded Cather and attempt to sketch the territorial imagination she acquired from it. We will also need to reconsider Cather’s firsthand experience of Nebraska, the heart of the region she called the West and always centered in her hometown of Red Cloud. By delicately (and provisionally) untangling memory and imagination in this analysis, we can begin to identify some of the crucial strategies and techniques that Cather inherited and redeployed in her fiction.

“The state of Nebraska,” Cather explained in 1923, “is part of the great plain which stretches west of the Missouri River, gradually rising until it reaches the Rocky Mountains.”2 Sounding like a traditional historian with this opening, she became more personal as she described the climate: “There we have short, bitter winters.” On the face of it, Cather was telling Nebraska’s story for a national audience, and the state was a “there.” But the author also wanted to say something about her place in this history. She wrote as a “we.”

Describing Mormon travelers and gold seekers, Cather ever so subtly affirmed, time and again, her place in this history. “When I was a child,” she wrote, “I heard ex-Governor Furness relate how he stood with other pioneers in the log cabin where the Morse instrument had been installed.”3 A few paragraphs later, she related, “I have heard the old freighters say. . . .” When she reached the 1880s, she declared, “The county in which I grew up, in the south-central part of the state, was typical.”4 Implicitly, there is no gap between the historian and her subject.

Like Cather’s life, the story of Nebraska had unfolded in decadal terms. She explained that the state’s “social history falls easily within a period of sixty years, and the first stable settlements of white men were made within the memory of old folk now living.”5 The first settlements were “made,” and the makers were still alive. In 1923, at the age of fifty, the first great maker of fiction and poetry set in Nebraska was joining the first makers of Nebraskan settlements in living, breathing memory. More than writing popular history, Cather was commemorating the emergence of both state and artist.

The classical Greeks used a particular word for this sort of making: ποίησις, poiesis. Although the term seems to suggest poetry, the Greeks understood a continuity between all sorts of making. In Plato’s Symposium, Diotima explains that humans embrace making because they want to transcend the eternal and inevitable cycle of life and death by leaving something of value behind.6 This, I suggest, is precisely how Cather was thinking of herself as she wrote her history of Nebraska. She saw herself as an aging maker living among older makers. The making—whether of settlements or art—was of a piece, and nothing less than a bold attempt to transcend a “cycle” of settlement and colonization, boom and bust, life and death.

Perhaps it is helpful to recall that the story of territorial making began in 1787 when the Congress of the Confederation passed the Northwest Ordinance, which invented a program of territorial self-government that would lead toward statehood. With a certain bureaucratic economy, the first sentence of the document establishes expectations that would inform territorial thinking for generations to come: “Be it ordained by the United States in Congress assembled, That the said territory, for the purposes of temporary government, be one district, subject, however, to be divided into two districts, as future circumstances may, in the opinion of Congress, make it expedient.”7 Territorial making would always anticipate unmaking in a larger poiesis governed by expediency and executed through division. A territory would always be a palimpsest, and the territorial imagination would always favor the palimpsestuous. Here, as we shall see over the course of this book, was a formula for territorial expansion that would eventually inform Cather’s approach to writing about the West.

Over the decades that followed, people of every stripe—politicians (visionary and mercenary), frontier scouts, fur traders, gold seekers, religious exiles, missionaries, ambitious investors, railroad magnates—mapped, remapped, and renamed the new territory. In the summer of 1803, Lewis and Clark found grapes, plums, and cherries along the present-day Nemaha River. They went on to the present-day Platte River where they met with the Otos and Missourias. This new world was both fecund and populated. In 1805, Zebulon Pike led the first great expedition through the region, and a distinct version of the territorial imagination was sown on the Great Plains. Pike’s Account of Expeditions to the Sources of the Mississippi, published in 1810, somewhat ambivalently introduced the English-speaking world to a country called “Nebraska” (GPF, 27–28).

Two years later, Cather’s Divide became part of the Missouri Territory. Eight years later, Congress passed the Missouri Compromise, which attempted to settle the ongoing dispute over whether slavery would be permitted in the new territories by creating a zone of freedom north of the parallel 36°30' north. That summer, Stephen H. Long was making his way along the river we call the Platte. His report, compiled by Edwin James, noted “a manifest resemblance to the deserts of Siberia.”8 Taking this conclusion to heart and committed to expediency, government officials created “permanent Indian boundaries” between the fertile United States and the “desert” west of the Missouri River.

Everything changed when missionaries began arriving in earnest in the 1830s, and “Oregon Fever” blossomed in the following decade as thousands passed along the Platte heading west. West observes, “Between 1841 and 1859, more than 300,000 persons and at least 1.5 million oxen, cattle, horses, and sheep moved up the Platte road.”9 At the peak of the migration in 1857, at least one hundred travelers a day arrived in Brownville, the territorial town that would play an important part in Cather’s vision of Nebraska.10

Over time, motion seemed to become the all-consuming imperative. In an important study of the phenomenon, Joseph Urgo declares that “the overarching myth, the single experience, that defines American culture at its core is migration: unrelenting, incessant, and psychic mobility across spatial, historical, and imaginative planes of existence.”11 It is of course one of the greatest—if not the greatest—paradoxes in American culture that the same space that inspired motion also enticed the movers to put down roots. The geographer Yi-Fu Tuan explains this seeming contradiction: “Human beings require both space and place. Human lives are a dialectical movement between shelter and venture, attachment and freedom.”12

The scale and difficulty of life in the Kansas-Nebraska Territory simply magnified this essential dialectic, the siren call of what Susan Stanford Friedman has called “roots and routes.”13 As Julie Roy Jeffrey points out, “transiency” was always part of the larger settlement/colonization process.14 In her own account of the great migration, Cather puts it this way: “The State was highway for dreamers and adventurers; men who were in quest of gold or grace, freedom or romance. With all these people the road led out, but never back again.”15 Actually, many people did go back, including Cather. A product of this migratory culture, Cather could look back in 1923 at a long life divided and defined (often paradoxically) by deep roots and well-traveled routes.

Not surprisingly, talk of dreams and adventures did not impress the Native Americans whose lands were being stolen. The term “Indian Territory” was “applied, removed, and reapplied, over and over again.”16 Settlement always involved displacement and appropriation. Black Hawk, the great warrior and leader of the Sauk, gave voice to the injustice: “You have split the country and I don’t like it.”17 Cather, for her part, seems seldom to have grasped the injustice of territorial expansion. She avoided real stories of appropriation and genocide in her fiction.18

Whatever else we make of Cather’s Nebraska, we need to remember this crucial story of its birth. In January of 1854 Iowa senator Augustus C. Dodge offered a bill for the creation of a new territory. No one was happy. So the Committee on Territories, led by Stephen A. Douglas, countered with a bill that divided Dodge’s territory in two. Nebraska would eventually become a Free State while the status of Kansas would be determined by popular sovereignty, or squatters’ rights.

On May 30, 1854, President Franklin Pierce signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which Roy F. Nichols has called “the most spectacular act in the drama of territorial history.”19 In the moment of its emergence, the territory was divided, doubled, and renamed. For generations to come, the people of the American West would take a simple proposition for granted: “When a human agenda was important enough, the Great Plains could easily be redrawn and renamed.”20 Ultimately, this sense of the region informed the way Cather and the other representatives of Nebraska’s “first cycle” thought about the place. As Cather would come to appreciate, Nebraska was all about imaginary lines, and one person’s imagination was bound to challenge another person’s fact.

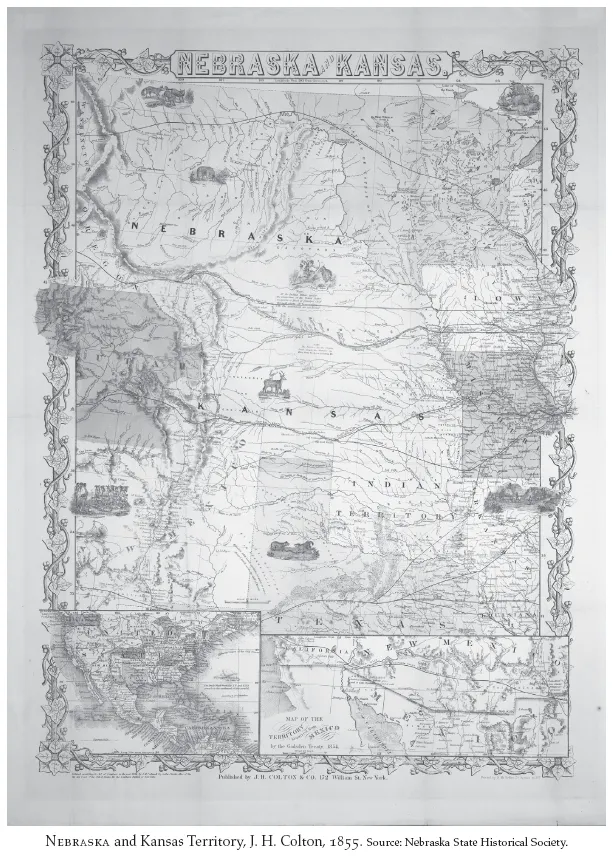

Territorial mapmakers certainly embraced this culture. An 1823 map identifies Cather’s future homeland as “Indian Territory,” with the added tag: “Deep Sandy Alluvion.”21 The map of the United States used in Mitchell’s School and Family Geography (1852) identifies the region of western Kansas as the “Great American Desert.” The J. H. Colton map for 1855 depicts a territory called “Kanzas.” What began as a series of finite real-world actions blossomed exponentially in re-presentation and so confirmed what Susan Schulten has called “the malleable nature of geographical knowledge.”22

At the same time, the maps reveal the aesthetic dimension of the territorial imagination. A. J. Johnson’s territorial map Nebraska and Kansas suggests the inventiveness (even the whimsy) of the act by dressing Kansas in a gaudy pink that splashes west over Pikes Peak and South Park in present-day Colorado. Sporting a lighter, more roseate hue, Nebraska dominates the document. It controls the plan with golden-haired authority, all the way north to the border marked as “British Possessions.” Years later, as she worked toward her own distinctive voice for the prairie, Cather took her place in this tradition by writing like a territorial colorist.

Particularly adept at using colors to highlight territor...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Red Cloud and the “Real West”: Mapping Willa Cather’s Territorial Imagination

- 2. Writing the West Otherwise: The Short Stories of the First Decade, 1892–1902

- 3. The Road from April Twilights into the Far Country

- 4. “a ride through a familiar country”: The Different Process of O Pioneers! and the Emergence of Willa Cather

- 5. Emergence, Experimentation, and Evolution: The Song of the Lark, My Ántonia, and the Fiction that Followed Out West

- Texts and Abbreviations

- Works Cited

- Index

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author