- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

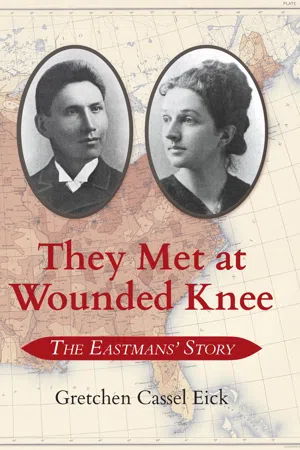

After ten years as a foreign and military policy lobbyist in Washington and four as director of an interfaith lobby, Gretchen Eick, moved to Kansas, earned a Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Kansas and became Professor of History at Friends University. She was awarded two Fulbright Scholar awards, teaching in Latvia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), and a Fulbright Hays to South Africa. Her book on the civil rights movement—Dissent in Wichita: The Civil Right Movement in the Midwest, 1954-1972 (U of IL Press, 2001/2007) won three awards: The Richard Wentworth award from the University of Illinois as the best book in American history that press published over two years, the University of Kansas' Hall Center Award for the best book by a Kansas author (the first time the award went to someone not teaching at K.U.), and the William Rockhill Nelson award for the best nonfiction book by a Kansas or Missouri author. The book resulted in two museum exhibits, a 2009 Telly Award-winning public television documentary about the first successful student-led sit-in, the 1958 Dockum Drug Store Sit-in in Wichita, and mention in the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9781948908733Subtopic

Biographies de sciences socialesPart 1

1

Beginnings

War distorts childhood. Children who survive war carry memories of violence, dislocation, hunger, and the search for refuge and safety. They also carry memories of the people who kept them alive and the stories that held them together. The collective memories that helped them survive desperate physical circumstances become closely held truths for the rest of their lives.

When he was only four years old, Ohiyesa—later called Charles Alexander Eastman—witnessed the Dakota War against the United States of America that began August 18, 1862. For his family that war was the central event of their lives. It forced them to flee their ancestral home in Minnesota and separated them from family. Some of them were killed. Some were imprisoned. Some died of exposure and hunger. Others, including Ohiyesa, became refugees in Canada.

The same month that the Dakota in Minnesota went to war against the United States, half a continent to the east, Henry and Deborah Goodale began married life at Sky Farm near the small New England town of Mount Washington in western Massachusetts. A little more than a year later, on October 9, 1863—while Dakota families fled the US Army’s campaign of extermination or tried to survive as refugees in Canada and South Dakota or as prisoners of war in Iowa—Deborah Goodale gave birth to the first of their four children. They named her Elaine.

The Goodales were intellectuals and writers. Henry’s heritage was Puritan. Deborah’s ancestors were Anglicans who had received land grants from King George, as Elaine wrote in her book, Journal of a Farmer’s Daughter (1881). Deborah was accustomed to prosperity, but Henry’s attempts to support their family through farming proved unsuccessful. Eventually his wife left him. Their hard times meant that their precocious eldest daughter had to seek paid employment rather than attend college.

Despite this acute disappointment—and her parents’ separation—eighteen-year-old Elaine remembered her childhood in the 1860s at Sky Farm in the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts as a time of “delicious abandon.” She cataloged the delights of each month—maple sugaring, collecting wild strawberries on the mountainsides, picking cherries, picnicking by wild streams, hunting partridge nests in the woods, preparing abundant home-grown food, gathering nuts, snaring rabbits, attending autumn county fairs. G. P. Putnam published her nostalgic narrative of life at Sky Farm when she was only eighteen.

Although they grew up half a continent apart, both Ohiyesa and Elaine idealized their difficult childhoods and wrote about them, Ohiyesa in Indian Boyhood, Elaine in Journal of a Farmer’s Daughter and Sister to the Sioux. Both experienced dislocation as teenagers that helped them identify with indigenous people who were repeatedly dispossessed of their land and forced to move.

Elaine learned of her heritage from the papers and artifacts stored in an old trunk in the attic of the farmhouse that she explored with her mother. Ohiyesa learned his heritage from the stories passed down within his family about his great-grandfather, Mahpiya Wiasta, stories about his Dakota people. Prominent among those stories were Dakota War stories, stories of the war against the United States that had divided his family and made him a refugee.

Mahpiya Wiasta, who the settlers called Cloudman, had raised his children and mentored his grandchildren with the conviction that the Great Mystery (God) always has a good intent for those who seek him. He was in his late sixties in 1862, as the whites counted. Nine years had passed since his band had made its fourth removal to only 640,000 acres of land on the south bank of the Minnesota River. In three major land sessions in 1805, 1837, and 1851, and twelve treaties, the Dakota lost northern Minnesota, about half of northern Wisconsin, and all but a ten-mile strip along the south side of the Minnesota River by 1862.1 His people especially felt the reduction in land for hunting in the lean months of spring and early summer, before the annual harvest of crops and the arrival of annuities. Thin bodies, drawn faces, and the high number of deaths among infants, children, and the elderly made them acutely aware that their survival was at risk.

Ohiyesa’s great-grandfather, Mahpiya Wiasta, was respected by both whites and Indians for his progressive views. As was not uncommon, three of his daughters had married prominent white men, traders or military men, and settled nearby their parents. His eldest daughter, Anpetu Inajinwin, had married Major Lawrence Taliaferro, the Indian agent in charge of the agency near Fort Snelling, a man respected by both Indians and whites. She had a child with him, but the marriage, like so many of these marriages, did not last long. His second daughter, Hanyetu Kihnayewin, married Scottish fur trader Daniel Lamont. His daughter Wakaninajiwin, also called Stands Sacred and known for her beauty and generous spirit, had married the American soldier Seth Eastman and had a girl child by him. When Eastman was reassigned to Louisiana—long before he would become famous for his paintings of the Dakota people, one of which hangs in the US Capitol—this daughter had moved with her baby into her parents’ home.2

Mahpiya Wiasta’s family with its mixture of Native and European American bloodlines was not unusual on the Great Plains, nor was it unusual for some of the family, including the granddaughter they called Nancy Stands Sacred Eastman, to be baptized Christian.

Nancy Eastman married Tawakanhdiota, a man from another Dakota band, and moved with her extended family to the ten-mile strip along the south bank of the Minnesota River that was the last remnant of Dakota land in Minnesota. There they expected to raise their children. Before the birth of her fifth child, a white man from Baltimore, Maryland, named Frank Blackwell Mayer, visited Mahpiya Wiasta’s village and made sketches of the residents, including Nancy Stands Sacred, granddaughter of Mahpiya Wiasta and daughter of Seth Eastman. Mayer published his sketch of Nancy in his book, With Pen and Pencil on the Frontier in 1851. Sadly, a few months after the birth of her fifth child, during the hungering season of spring, 1858, the beautiful young woman died of strep throat. She was only twenty-eight. Death was all too common in the reduced circumstances of the Lower Sioux Reservation, especially for children, the elderly, and women who had recently given birth.3

On her deathbed Nancy directed that her husband’s mother, not her own mother, should be the one to raise her four-month-old son. Nancy’s grandmother, Mahpiya Wiasta’s wife, was furious with their granddaughter’s decision. Their band followed a matrilocal pattern of residence, meaning married couples lived with the wife’s people. Nancy’s deathbed decision meant that their great-grandson would move from her band to his father’s band.

The community respected the dying mother’s decision. The baby was raised by his paternal grandmother, whom he would call Uncheedah (Grandmother). Had the child lived with his mother’s people, he likely would have died in the concentration camp outside Fort Snelling that held them by the end of 1862.

Uncheedah swore she would not let her newest grandson die, and she did not. They called him Hakadah (The Pitiful Last) because of his slim chance of surviving, but he responded to her determined ministrations, ate the gruel of pounded wild rice that she gave him in place of his dead mother’s milk and, against all odds, survived. In late 1862, Uncheedah would flee to Canada carrying her grandson on her back, traveling more than four hundred miles to refuge. She would save his life. His extraordinary achievements began with her.4

On July 14, 1862, when the child Ohiyesa was four, five thousand Dakota camped at Redwood Agency hoping to receive their annuities. Agencies were the administrative centers of reservations, where traders and US government officials lived. A US government-appointed agent was in charge and distributed the annuities the US government promised to reservation inhabitants as payment for surrendering their land to the United States However, the annuities were late, again. Two weeks later the Dakota returned to the Agency to receive the promised foodstuffs and cash. Again, they were turned away. White observers commented that the Dakota waiting around the Agency for their annuities

were so pinched for food that they dug roots to appease their hunger, and when [seed] corn was issued to them they devoured it whole and uncooked. Several died from want of food. They [the Indians] determined that when the annuities arrived, [if they were given to the traders who kept the only records of who owed them money—a practice that had occurred regularly in the past] the traders should not receive them [the annuities], and if they insisted, then the Indians would rob the stores, chase the traders from the reservation, or take their lives, as they might deem best.5

Frustration multiplied each time the hungry Dakota were turned away empty-handed.

Mahpiya Wiasta’s great-grandson was four and a half in August 1862, when his father, Tawakanhdiota—called by the English, Many Lightnings—made a third trip to the Agency of the Lower Sioux Reservation with the other younger men of the band to collect the US government annuities. The annuities so crucial to their survival were now two months late. Again, their trip was unsuccessful. Two weeks later, desperate for food, they made the trip once more, a fourth time, returning frustrated and angry.

Agent Galbraith was a Lincoln political appointee with no experience working with Indians. He had been on the job only a year. He refused to distribute the supplies that had arrived because he did not want to go to the trouble of making two distributions. He insisted they must wait until everything arrived. He had not calculated how his refusal to distribute any of the provisions that had already arrived would affect the starving Dakota.6

The hereditary leaders of the bands and the young warriors engaged in much intense conversation about how the agent treated them. One of their leaders, Taoyateduta (Little Crow), had been present at the Upper Sioux Reservation at Yellow Medicine a few days earlier. There the agent had distributed some provisions to the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of Dakota. Taoyateduta asked Agent Galbraith to treat the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands the same way because they were hungry. But Agent Galbraith refused, insisting it was inefficient to make two distributions and saying the cash annuity was expected any day. He seemed oblivious to how “inefficient” and infuriating it was for the Dakota to make multiple fruitless journeys to the reservation.

In earlier years traders who lived among the Dakota and took Dakota wives would be generous, knowing how desperate the Dakota were for food. But not in August 1862. Now the traders who served the Redwood Agency refused to sell supplies to the Dakota on credit. Some of the warriors threatened to prevent the traders from continuing to take unreasonable profits off the top of the people’s annuity money. Some Dakota predicted that no annuities would arrive because the Civil War was consuming all the US government’s money.

Everyone was talking about what Taoyateduta said to Agent Galbraith after he and the traders refused them relief: “We have waited a long time. The money is ours, but we cannot get it. We have no food, but here are these stores, filled with food. We ask that you, the agent, make some arrangement by which we can get food from the stores or else we may take our own way to keep ourselves from starving. When men are hungry, they help themselves.” Trader Andrew J. Myrick told the Dakota, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass!”

The entire gathering fell silent at these insulting words. Then the Dakota men, in a mighty chorus, began making war whoops and left the agency.7 The agent and the traders at the Lower Agency who had denied sustenance for the families of the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands would pay a high price for their hard hearts.

Two days after this exchange between Taoyateduta and Agent Galbraith, four teenaged Dakota, hungry and debating the rights and wrongs of eating a white settler’s hen’s eggs, provided the spark that ignited the Dakota War against the United States.8

Early on the morning of August 17 word came to the Dakota bands that four young men from Shakopee’s band had returned from the white settlement at Acton greatly agitated. They had found a nest of hen’s eggs. One of them had proposed they eat the eggs because they were very hungry. Another cautioned him not to, that he would get them in trouble since the eggs belonged to a white man. The first youth taunted the others. They must be cowards, afraid of white men. This they hotly denied. To demonstrate their bravery, one proposed they enter the white man’s house and shoot him, which they did. The gunshot roused a nearby household, leading the youths to kill those whites as well. They boasted that they had killed four white men and two women. Then they hitched up a team of horses and rode back to Shakopee’s Village.

Late that night after a long meeting, the warrior society leaders went to Taoyateduta and insisted he support an all-out war against the whites and their mixed-blood allies for the purpose of taking back the Dakota’s land. The timing, they argued, was auspicious with the US Army’s war against the states of the Confederacy going badly. Taoyateduta was reluctant, but their anger and arguments were persuasive to many. Eventually he agreed to declare war on the United States of America.9

Elders more experienced with whites, including Mahpiya Wiasta, viewed war with the United States as shortsighted and dangerous. Yes, the territorial governor had recruited mixed-bloods as well as whites to fight in the Civil War in the South, but that did not mean there were no men left to fight an Indian uprising in Minnesota. Yes, the papers reported reverses and defeats for Mr. Lincoln’s army, but that did not mean that the United States would lose its war against the Confederacy. Yes, the Dakota had fought with the British in the War of 1812, but that did not mean that the British would defend Dakota rights to Minnesota. What was more likely was that the Dakota would be defeated, and, as had happened so often in the last 200 years, the whites would then seek revenge against all Red Men, regardless of whether they had supported or opposed this Dakota War. The toll would be terrible. Even this slim strip of Minnesota land would likely be lost to the Dako...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Part 1

- Part 2

- Part 3

- Part 4

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access They Met at Wounded Knee by Gretchen Cassel Eick in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.