![]()

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Gray Ocean of Sagebrush

The relentless silver gray reflection of the cold desert’s sagebrush landscape could not help but impress those first few travelers who ventured West. Oregon-bound travelers got their first taste of sagebrush near Fort Laramie, Wyoming, and the gray ocean of sagebrush increased as they proceeded westward. John C. Frémont had difficulty getting a wagon through the dense stands of sagebrush on the Snake River Plains. The perennial grasses that did exist within the sagebrush were mature, dry, and harsh when the Oregon settlers reached the sagebrush plains in early autumn.1

The endless uniformity of a sagebrush-dominated landscape tends to blur differences and hide the details of this land’s plant communities. Sagebrush/grasslands are plant communities in which species of sagebrush form an overstory and various perennial grasses form the understory. In western North America, from southern Canada to northern Mexico, a group of closely related sagebrush species comprise an endemic (i.e., occurring here only) section of the worldwide genus Artemisia.2 They occur in varying amounts over 422,000 square miles in eleven western states. Sagebrush/grasslands occur in all the western states, but the discussion here focuses on the range plant communities of the Intermountain area.

The Intermountain area is the vast region from the Rocky Mountains on the east to the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges on the west. It is bounded on the south by the true warm deserts and on the north by coniferous forests. The Intermountain area is a cold desert—a semiarid to arid region where the winters are bitterly cold and often snowy.

How did the first settlers to enter this area view it? Anthropologists use the term “contact period” to indicate the period of first contact between indigenous cultures and European or American trappers, explorers, and settlers. Sources of information for the contact period in western North America are largely trappers’ journals often written or edited after the actual contact in the field. Their major subject is the fur trade, with comments on the general environment usually secondary. Comments on plant communities are frequently no more than asides and often must be interpreted from other statements. Since trappers tended to travel and camp in river or stream valleys where beavers were likely to be found, most of the written comments concern these areas. The mountain ranges of the Great Basin tend to run north and south and are oriented in echelon, and travelers could avoid crossing them by going around them. Nineteenth-century travelers tended to group all shrubs in the Intermountain area as sage or wormwood even though the trails passed through greasewood- or saltbush-dominated landscapes. Essentially, one can use the records left by trappers and early explorers of the Intermountain region to confirm preconceived ideas of the pristine vegetation of the sagebrush/grasslands.

The extensive records kept by the early Mormon colonists provide the best account of the pristine sagebrush/grasslands environment. George Stewart, who was then with the Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, summarized the available records in 1940. Stewart was uniquely trained and experienced for the role. After first becoming a successful agronomist and college teacher, he joined the Forest Service as a range ecologist. Stewart’s position in the Mormon Church gave him access to the records of the early church colonies. It is interesting that Stewart takes quotations from the journals written during the contact period to emphasize the abundance of grass under pristine conditions, while T. R. Vale, who examined many of the same sources, concludes the opposite and stresses shrub dominance.3 Generally, the records indicate that the abundance of shrubs increased as the Mormon settlers moved westward and southward in the Intermountain region until they passed into true desert vegetation.

Early travelers along the Oregon Trail had the opportunity to view a good cross section of the sagebrush ecosystem from Fort Laramie to the Columbia River. Their opinion of the sagebrush country was partially dependent on the time of the year they crossed the Snake River Plains.4 The journals of those who crossed the area in late summer or early fall stress the sagebrush, lack of forage, and dust. Because of the time interval required for an overland journey from Missouri to Oregon, most travelers crossed the sagebrush/grasslands during the late summer, after they had traveled through the Great Plains, one of the world’s foremost grasslands. Thus, the travelers crossed the plains during the peak of the growing season, and the sagebrush/grasslands obviously suffered by comparison.5

Anglo-American exploration and fur trading began in the Snake River area in 1809 and continued until 1846.6 Most of the activities of the fur trappers were confined to the upper Snake River and adjacent areas. However, the hunt for beavers was much like the later prospecting for gold; the trappers followed virtually every stream in search of wealth. Peter Skene Ogden, who commanded the Snake River Brigade for the Hudson’s Bay Company, left detailed and believable records of his extensive travels in the Intermountain region.7 The Snake River Brigade traveled with two hundred horses used for riding and for carrying supplies, traps, and furs.8 These animals depended on forage obtained along the line of march and in the vicinity of winter camps. The trappers who composed the brigade were avid hunters. When the brigade traveled in the eastern Snake River country where there were American bison, the hunters would exasperate Ogden with their wanton killing of game animals and failure to pay attention to the business of trapping. However, when the brigade was traveling in the Great Basin and south-central Idaho, forage for the horses was easy to find, potable water was scarce, and big game for food was difficult for Ogden’s professional hunters to locate.

The initial settlements in much of western North America were established either at convenient points along transportation routes or at sites where important minerals were discovered. The Mormon settlements of the Intermountain area were an exception to this rule. The Mormons had to pick specific environments suitable for agriculture if they were to survive. Within thirteen years after Salt Lake City was founded in 1847, a series of outlying Mormon colonies had been established from Lemhi in Idaho to Genoa, Nevada, to San Bernardino, California. The sites for these settlements were carefully selected to include areas suitable for irrigation to support intensive agricultural and grazing lands capable of producing the meat, milk, and draft animals necessary for the colonists’ survival. The extensive records kept by these early colonies provide the best descriptions of the environment available for the development of productive sagebrush/grasslands.

In the late eighteenth century, the American bison occasionally extended its range across the northern portion of the sagebrush/grasslands into northeastern California, the Malheur and Harney Basins of eastern Oregon, and even to the Columbia Basin. This is roughly the bluebunch wheatgrass portion of the sagebrush/grasslands. The American bison had withdrawn from northern Nevada long before historic times. Therefore, the Thurber’s needlegrass portion of the sagebrush/grasslands had no concentrations of large herbivores under pristine conditions. In the early nineteenth century the number of American bison on the upper Snake River and Green River drainages increased as a result of hunting pressure east of the Rocky Mountains; after 1830, the populations west of the mountains were exterminated. The spread of trade that provided rifles to the Indians hunting for robes, promiscuous hunting by trappers, and several severe winters contributed to the bison’s demise.9

The buffalo, or American bison, is the only large herbivore to exist in large numbers on the sagebrush/grasslands during recent geologic times.10 At the close of the Pleistocene, the upper Snake River Plains were grazed by native species of mastodon, camels, horses, and ancestors of the American bison. All of these animals but the bison became extinct, and rabbits, rodents, and harvester ants became the major consumers in the sagebrush/grasslands. Certainly the pronghorn remained, but pronghorns were scarce in the Intermountain area and very scarce in the Great Basin. The Goshute Indians of Deep Creek in eastern Nevada practiced the communal activity of driving pronghorns with systems of traps, blinds, and barriers. Under pristine conditions the pronghorn populations in the various eastern Nevada valleys were sufficient to support only one of these drives each decade. It is no wonder the fur trappers had a hard time finding camp meat in this region.11

In contrast to the members of the deer family, which are fairly recent emigrants from Asia by way of the Bering Strait land bridge, the pronghorn is a true native of the sagebrush/grasslands of North America. The females bear their young in May, and the kids are soon following their mothers through the sagebrush. Bands of three to twenty animals are common in summer, and in winter the pronghorns collect in even larger bands. They are migratory in the sense that those in the higher elevations of the summer range move down to lower territory where there is less snow in winter, but essentially pronghorns always live in the sagebrush/grasslands.

Many of the rodent species that populate the sagebrush/grasslands are adapted to utilize metabolic water to satisfy their moisture requirements. They seldom, if ever, actually drink water, and instead obtain their moisture requirements from the food they eat. This gives them a tremendous competitive advantage over the large herbivores, which are limited to grazing within the range of infrequent waterholes. A second adaptation of many of the rodent species is the use of underground burrows, which moderate the environmental extremes of the Great Basin.

The black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus) is probably the most common consumer of plant material in many parts of the sagebrush/grasslands. A traveler across Nevada sees more jackrabbits of this species than all the other small animals combined. The black-tailed jackrabbit is abundant in virtually all of the lower-elevation sagebrush areas. A black-tailed jack was spotted a mile out on the barren Fourteen-Mile Salt Flat east of Fallon, Nevada, and one was killed at 11,700 feet on Mount Jefferson in Oregon, illustrating the range of the species in the Intermountain area.12

Numbers of this species fluctuate so markedly that almost every Nevada resident has noted the phenomenon. The cause of the sudden crashes in rabbit populations may be tularemia, a bacterial disease caused by Bacillus tularense, which also attacks man. In jackrabbits, the mortality rate may reach 90 percent of populations. When the black-tailed jackrabbit populations are near their peak in a given area, they can be extremely destructive to crops, especially to irrigated fields in a generally sagebrush environment. Under pristine conditions, the white-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus townsendii) was probably much more abundant than the black-tailed jackrabbit.

Reconstruction of the pristine environment is not limited to historical records. Range ecologists are continually looking for relic areas where plant communities exist in equilibrium with the natural environment. Such areas remain because of natural “fencing” such as a mesa with sheer walls or lava flows that stock cannot cross; steep slope angles; or distance from stock water. In the sagebrush/grasslands water points are scarce and unevenly distributed across topography that is often rugged. This creates uneven utilization by grazing animals leaving areas long distances from water or on steep slopes ungrazed.

To look at the present sagebrush environment with an eye to differences in the past, one must understand the complex vegetation structure behind this gray landscape. It is necessary first to learn the identity of the major plant species, and then to recognize how the plant species fit together to form communities.

Within the Intermountain area there are two major subdivisions: the Snake River drainages and the Great Basin. The Snake River is part of the Columbia system, which also contains the Columbia Basin, a region that historically supported a northern extension of the sagebrush/grasslands. In southern Idaho, the Snake River flows into a deep canyon walled by nearly vertical basalt cliffs. On top of these cliffs are extensive undulating plains that were formerly clothed with sagebrush—the Snake River Plains.

Across a mountainous divide south of the Snake River Plains lies the other subdivision of the Intermountain area, the Great Basin. The Great Basin is a physiographic area with somewhat indefinite boundaries (see Figure 1). Roughly, it lies between the Sierra Nevada on the west and the Wasatch Mountains on the east, but its tributary valleys extend to Wyoming. To the southeast, it grades into high plateaus near the Colorado River. Southward, the province extends through the Mojave Desert of California in Baja California. Thus, the Great Basin includes most of Nevada and Utah with fringes in California, Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming. The name “Great Basin” was first applied by Frémont in 1844 when he scientifically established that no water drained into the ocean from this huge area.

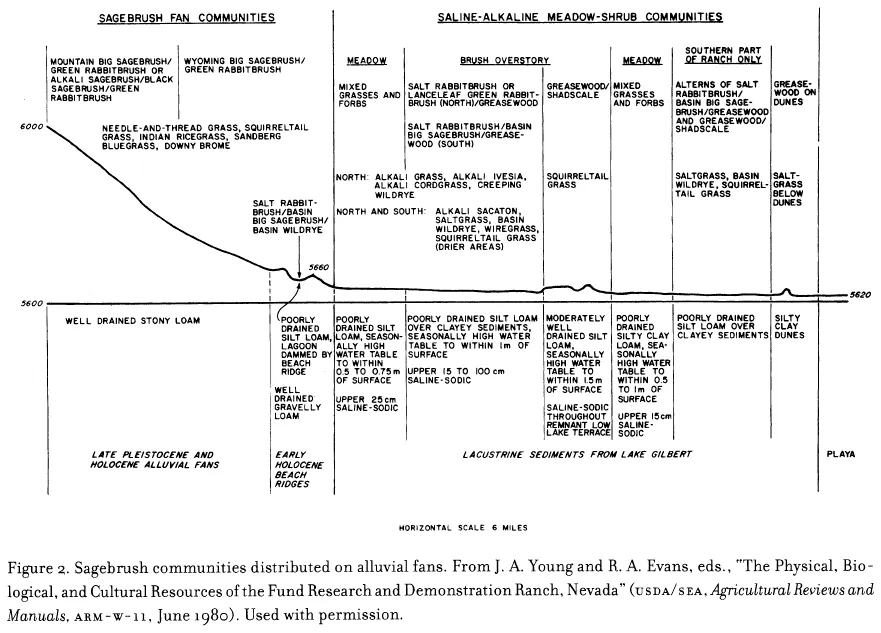

The plant communities of the sagebrush/grasslands are a measure of the potential of the environment (see Figure 2). The history of the exploitation of the sagebrush/grasslands is also reflected in the present plant communities. The walls of flames exploding through the big sagebrush/grasslands of Elko County in 1964 were a vivid expression of this history.

Pristine plant communities in equilibrium with their environment are adjudged to be in excellent range condition. As the plants that compose the pristine community change in abundance—with, for example, the unpreferred shrubs increasing and the desirable perennial grasses decreasing—range condition drops to good, fair, or poor. The direction range condition is proceeding—either downward toward a degenerated condition or upward toward equilibrium—is called range trend. Range condition and trend are the basic concepts used to evaluate the impact of grazing animals on the environment. Obviously, knowledge of the pristine environment before domestic livestock was introduced is vital to establish condition and trend standards.13

There are many kinds of sagebrush growing in the sagebrush/grasslands, but the species that generally characterizes the environment is big sagebrush, Artemisia tridentata. This scientific name was first given in 1841 by Thomas Nuttall to plants collected from the plains of the Columbia River.14 Big sagebrush is normally an erect shrub three to six feet tall, although dwarf forms occur occasionally. The trunk of the shrub is definitely woody with a stringy, fibrous bark. The silver gray hairs on the leaves and new twigs give the entire plant a light gray-green appearance. The light color of the leaves reflects much of the sun’s incoming radiation and protects the plants from desiccation in the arid environment. The leaves persist through the winter, and when the current year’s growth begins in early spring, it is difficult to distinguish it from previous seasons’ growth. Flower heads appear in midsummer, with flowering in late August and September. The yellowish flowers are borne in clusters on flower stalks. The brownish black seeds begin to fall in October, and some persist until spring.15

Three characteristics of big sagebrush are especially significant to its grazing ecology: (1) this landscape-dominant shrub does not resprout when the aerial portion of the plant is burned in wildfires; (2) the species is composed of many ecologically distinct subspecies that in appearance or morphology are difficult to distinguish; and (3) the essential oil content of the herbage of big sagebrush inhibits the growth of the rumen microflora in cattle and, to various degrees, other ruminants.

The fact that big sagebrush does not sprout after being burned in wildfires has fundamental significance in the ecology of the species. The role fire played in the pristine environment of the sagebrush/grasslands is difficult to assess. In forests, the frequency of past fires can be determined by examining fire scars left on the trunks of trees. These scars, or “cat faces,” indicate the frequency of past fires that damaged the cambium layers in the annual rings of the trees.16 In the sagebrush/grasslands, however, there are no trees to record the frequency of fires. Under pristine conditions, wildfires eliminated the landscape’s dominant shrubs and essentially released the native perennial grasses from competition. The native perennial grasses mature more slowly than the exotic invader cheatgrass. Thus, the fire season for pristine sagebrush/grasslands must have occurred in late August and early September rather than the mid- to late-summer fire season seen with cheatgrass.

After the big sagebrush has been consumed in a wildfire, the community that reoccupies the site is not devoid of shrubs. A number of shrubs that are subdominants to big sagebrush resprout from their roots or crowns af...