- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Of all economic recessions experienced by the United States in the postwar period, the Great Recession that began in 2008 was the deepest, longest, and most destructive. Nevada was among the hardest hit states, its people reeling from the aftereffects, and the state government also experiencing a severe fiscal crisis. University of Nevada economics professor Elliott Parker and then-State Treasurer Kate Marshall make sense of what went wrong and why, with the hope the state will learn lessons to prevent past mistakes from being made again.

This is a different kind of economics book. Parker uses his expertise from doing research on the East Asian fiscal crisis to give profound insights into what happened and how to avoid future catastrophes. Marshall personalizes it by providing vignettes of what it was actually like to be in the trenches and fighting the inevitable political battles that came up, and counteracting some of the falsehoods that certain politicians were spreading about the recession.

Parker and Marshall's book should be required reading for not only every single elected official in Nevada, but for any private citizen who cares about the public good.

This is a different kind of economics book. Parker uses his expertise from doing research on the East Asian fiscal crisis to give profound insights into what happened and how to avoid future catastrophes. Marshall personalizes it by providing vignettes of what it was actually like to be in the trenches and fighting the inevitable political battles that came up, and counteracting some of the falsehoods that certain politicians were spreading about the recession.

Parker and Marshall's book should be required reading for not only every single elected official in Nevada, but for any private citizen who cares about the public good.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nevada's Great Recession by Elliott Parker,Kate Marshall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Nevada’s Great Recession

The only way in which a human being can make some approach to knowing the whole of a subject, is by hearing what can be said about it by persons of every variety of opinion, and studying all modes in which it can be looked at by every character of mind. No wise man ever acquired his wisdom in any mode but this; nor is it in the nature of human intellect to become wise in any other manner.

— JOHN STUART MILL1

Introduction

Of all economic recessions experienced by the United States in the postwar period, the Great Recession that began in 2008 was the deepest, longest, and most destructive. Of all states in the union, Nevada was the hardest hit. Nevada has long had a history of being low on the lists you want to be high on and high on the lists you want to be low on, but it became a state of superlatives: it had the highest unemployment rate, the largest fall in average income, the greatest share of population entering poverty, the biggest drop in housing prices, the highest foreclosure rate, and the greatest percentage of mortgages underwater.2 It also experienced a severe government fiscal crisis that lacked superlatives only because it had one of the smallest state governments in the country.

The two of us were well placed to watch this train wreck as it occurred. Kate Marshall served two terms as Nevada’s elected state treasurer, from 2007 to 2014, and it was her job to manage the state’s investments and make sure that the state had the cash flow to pay the bills the state legislature had budgeted for. This became extremely challenging as the recession developed into a depression. As for me, Elliott Parker, I was (and remain) professor of economics at the University of Nevada, Reno (UNR).3 Elected to serve as chair of the university’s faculty senate, I was near the center of the university’s efforts to cope with the crisis. Immediately afterward, I became chair of the Department of Economics, where I tried to encourage my colleagues to do a better job bringing their expertise to the people of Nevada.

I had come to my interest in Nevada’s economy by a circuitous route. My doctorate, my teaching experience, and my published research were all focused on comparative international economics, and I dreamed of making my university a center of international studies. I had grown to love Nevada, but when Professor Bill Eadington, my late colleague, asked me to apply my economic studies to Nevada’s economy, I did not take him very seriously. Even my own mother told me I should pay more attention to understanding those economies closer to home.

For more than a decade, however, I had been doing research on the effects of financial crises in East Asia, and this had led me to try to better understand how some recessions were distinctly different from others. Price deflation could deepen a recession and even become a self-fulfilling prophecy. In the wrong circumstances, financial crises could cause deep and long depressions. And then, in 2008, everything I had learned about other countries suddenly came home, and Nevada was at the epicenter. I knew that we were in the middle of something distinctly different, and that our normal ways of coping would not be enough.

Like most of my colleagues, I had preferred to keep my head down and focus on my students and my research, though in 2006 I had been lucky enough to be invited by Senator Harry Reid of Nevada to visit the U.S. Capitol building and present a short paper to the Senate Democratic leadership. A couple of years later, when Regent Bill Cobb visited the faculty senate to encourage faculty to get more involved in the greater community, I decided I needed to speak out to try to provide balance in light of the nonsense that some politicians were saying about the recession. Perhaps because I was recently divorced and hated coming home to an empty house, I made myself busy. I began to give talks and submit columns to newspapers across the state, to help other Nevadans better understand our situation.

In the middle of the crisis Kate and I would meet occasionally for coffee. Kate wanted my advice, as she looked for advice from many others, because she wanted to make the best possible decisions about the state’s finances. I wanted to help, of course, but I also wanted reassurance that at least some people in state government knew what they were doing, and understood how bad the crisis could become.

Kate would later run for Congress, in a district that has never been won by a Democrat. After her almost-inevitable loss, our professional relationship turned romantic. The two of us began dating in the fall of 2011, and we were married in the spring of 2014, each bringing two teenage children from a previous marriage.

This book contains new material, particularly Kate’s vignettes, plus a lot of material that was previously published as op-ed columns in newspapers such as the Las Vegas Sun, the Nevada Appeal, and the Reno Gazette Journal. These columns relied on the most current data available at the time. Because these data are often updated or revised, the numbers cited are not always precisely consistent from column to column, but the story that the data tell is always consistent.

In this first section, I provide an introduction to Nevada’s great crisis. I review Nevada’s peculiar history, and trace out themes such as education and fiscal policy that permeate the entire book. I then give a broader economic context for the problems Nevada faced, since these are problems shared with many small states during big crises.

Chapter 2 focuses on Nevada’s fiscal issues, and contains seven columns published between 2009 and 2011. Chapter 3 includes seven more columns published from 2008 to 2011, and discusses the proposals by Governor Jim Gibbons (2007–11) and Governor Brian Sandoval (2011 to present) to cope with collapsing revenues by shrinking the state’s government. Chapter 4 contains eight more columns on budget cuts particular to higher education, specifically my own UNR.

The next two chapters look to the national context for Nevada’s crisis. Chapter 5 includes eight columns written about the U.S. economy between 2011 and 2014, and starts with observations written a decade after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. In Chapter 6, we include seven columns on taxes, the federal budget deficit, and the so-called fiscal cliff crisis of 2012.

Chapter 7 comes back to Nevada with five columns written from 2013 to 2015 on Nevada’s slow recovery. Chapter 8 then adds nine columns we coauthored in 2015 that reflect on some of the problems that economic recovery has left exposed. These are issues that need to be faced as the state tries to create itself anew. We end with a short conclusion in chapter 9 to wrap up some of the lessons learned.

1. Causes of the Crash

The crash of 2008 was more than a decade in building. The Roman historian Tacitus once wrote that success has many parents, while failure is an orphan.4 But the economic failure of the Great Recession had many causes.

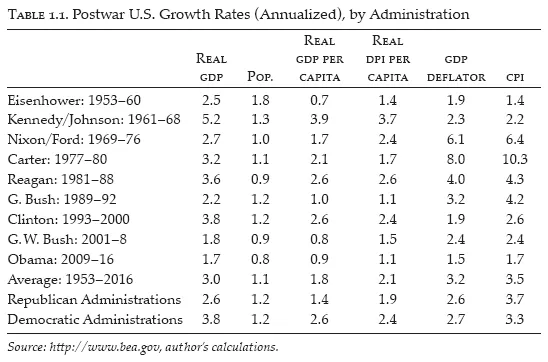

In the first place, crashes are initiated by booms, and the 1990s were a good decade for the U.S. economy. Growth rates were relatively high, price inflation was low, poverty was declining, the federal government budget was on its way from deficit to surplus, and interest rates were low. Table 1.1 shows the average annual growth rates for the United States after 1952, by presidential administration. Both gross domestic product (GDP) and after-tax disposable personal income are adjusted for both inflation and population growth. Two measures of inflation are shown, the official GDP deflator and the consumer price index (CPI). It is clear from this table that the Clinton years were topped only by the economic boom of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. This was especially true for the stock market; adjusting for inflation, the Dow-Jones index grew by an average rate of 9.7 percent per year, and the Standard & Poor (S&P) 500 grew by 8.6 percent, a record that only the Obama administration came close to matching.

Rising incomes in the 1990s led more people to purchase homes. Between 1994 and 2004 the United States had 15 million new owner-occupied homes, 6 million more than can be explained by population growth alone. Both California and Nevada, states that had relatively more renters than the rest of the nation, began to catch up.

Second, changes in the regulatory environment made it easier for many people to get mortgages. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, passed by a Republican Congress and signed by President Clinton, removed many restrictions on how banks did business. Most famously, it repealed the Glass-Steagall Banking Act of 1933 that kept commercial banks out of more-risky securities markets, but it also removed regulatory oversight of investment bank holding companies, and retroactively legalized a wave of mergers and financial consolidation.

One of the effects of this deregulation was a rapid expansion in the derivatives market. A derivative is a financial asset derived from other assets, like a stock option or a future price guarantee. When these markets work well, they allow investors to purchase a financial insurance policy, to hedge against the unexpected, in the same way that a homeowner might buy insurance against the chance of flood or fire. But normal insurance markets are regulated. Among other things, homeowners cannot buy insurance on somebody else’s home, insurers must maintain adequate capital reserves to make sure they can pay off when disaster strikes, and both the buyer and the seller understand the risks and payouts. Derivatives markets became much more complex, however, and lacked the clarity of normal insurance markets. New types of assets, like credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations, brought risks that neither buyer nor seller really understood.

A third factor was human nature, especially since it was about money. Yogi Berra is supposed to have said that it is tough to make predictions, especially about the future.5 Financial markets are inherently risky because they involve forecasting the unknowable. Investors often look to price behavior for signs of what other people think; this herding behavior can lead to what economists sometimes call the Biggest Fool Theory. That is, an investor who buys an asset based on its recent price behavior is a fool, but if he is a lucky fool he can find a bigger fool to sell it to. Eventually, however, the biggest fool enters the market, buyers evaporate, and the speculative bubble bursts.

In the late 1990s the United States saw a bubble in technology stocks, a bubble exacerbated by the so-called Y2K problem. Due to memory limitations, most computer programs written before the 1990s used only two-digit fields for dates; the danger that the year 2000 posed for a computer network collapse led to high spending on new software, new equipment, and programmers to fix existing software. Once the emergency passed, spending slowed. The NASDAQ, the second-largest stock market in the United States, had quickly tripled and then just as rapidly returned to earth. The result was an economic slowdown that turned into a recession after the events of September 11, 2001. The Federal Reserve Bank took monetary action that dropped interest rates, and the federal government implemented a ten-year tax cut that turned federal budget surpluses back into deficits.

As the economy began to recover from the 2001 recession, investors began looking for the next big thing, and a worldwide glut of savings began finding its way into the U.S. market. These foreign savings inflows not only led to rising trade deficits, since every dollar a foreigner spends buying U.S. assets is a dollar not spent on U.S. exports, they also helped to finance growing federal budget deficits and left financial markets awash with cash looking for a higher rate of return.

For five years, the result was a financial free-for-all. Housing prices began to rise at unprecedented rates, especially on the coasts. With low interest rates and the assumption that housing was a safe bet, Americans began borrowing more to buy bigger houses, and using their home equity to finance not only home remodeling but also college costs, vacations, and even gambling in Las Vegas. People with limited means bought several houses at a time, intending to flip them for a quick profit. A colleague of mine once said there is no pain so great as watching your neighbor get rich from doing dumb things.

Subprime markets with higher default rates grew to almost 10 percent of the mortgage market. Mortgage brokers could earn their commissions without taking responsibility for the creditworthiness of their customers, and so-called liar loans made it possible for people to take on mortgages they could not afford. Ratings agencies earned higher commissions for better ratings on securitized mortgage assets, and even the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) and Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) began to reduce the quality of the loans they resold as investment-grade securities in order to protect their market share from the growing competition from investment banks.

Many Nevadans saw the housing boom as the next great bonanza. The state had the nation’s fastest-growing population for decades, but now the state began building homes at a run. Californians moved to Nevada looking for more-affordable homes, as well as lower taxes, and other people came to Nevada to build those homes. Nevada soon was building homes for construction workers who were moving to Nevada to build homes for other construction workers. In fact, Nevada had twice the proportion of construction workers in the workforce as the rest of the nation, and the highest rate of any state. Nevada also had the highest proportion of new homes, along with the highest proportion of new mortgages.

Housing prices finally peaked in 2006, and soon sellers could not find buyers. Once home prices began to decline, housing starts plummeted, and contractors began to lay off their construction workers. By the end of 2007 it was clear that the economy was entering a recession. The Bush administration, which had used tax cuts in 2001–2 to stimulate spending, once again proposed tax cuts to address the economic slowdown. The Economic Stimulus Act of February 2008 included a recovery rebate of up to $300 per taxpayer plus tax incentives for business investment, but the increase in consumption spending was almost precisely offset by increased imports. As one wag put it, we borrowed from China to pay for tax cuts that were spent on goods from China, and were puzzled why it didn’t seem to help our economy.

As home prices continued to fall, defaults began to increase and many assets once considered safe now looked increasingly precarious. Losses rose, and big investment banks began to sell off their holdings before the bottom dropped out. In March 2008 the investment firm of Bear Stearns failed and was bought up by JPMorgan Chase at 7 percent of its previous value. In September 2008 Lehman Brothers closed; its bankruptcy filing was the largest in U.S. history. The resulting panic led the Bush administration to propose an unprecedented bailout of the financial sector through the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of October 2008, which provided $700 billion to purchase troubled assets and keep financial markets from collapsing.

In the last quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009, almost 4.3 million jobs were lost. By the end of 2009 the U.S. economy employed 8.6 million fewer people than it had two yea...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Introduction to Nevada’s Great Recession

- 2. Understanding the State Budget

- 3. Cutting State Spending

- 4. Cutting Higher Education

- 5. The National Economy

- 6. Federal Fiscal Policy

- 7. Returning to Normalcy

- 8. Nevada Matters

- 9. The Canopy of Hope

- About the Authors

- Index