![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Future Growth and Prosperity Is Assured

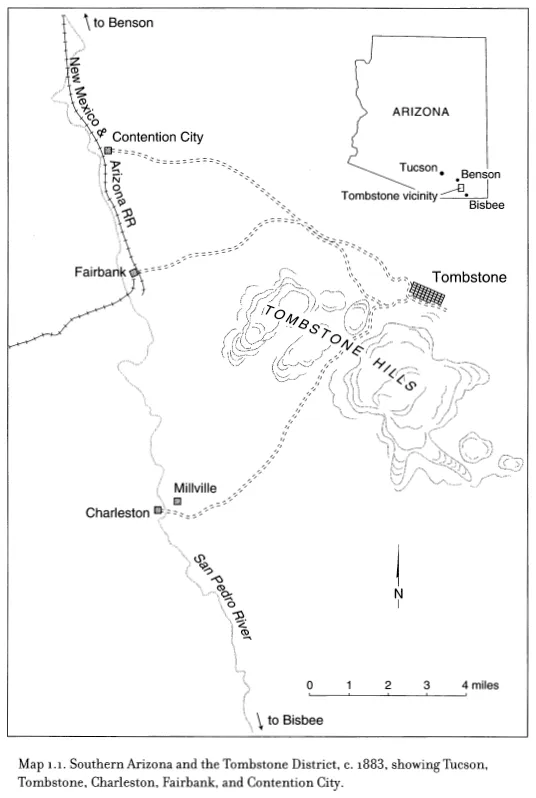

Nineteenth-century mining camps are famous for being located in forbidding places. The Tombstone District was certainly one of them. John Gray, who as a young man made the stage trip from the railhead a few miles east of Tucson to Tombstone in June 1880, wrote many years later:

That day’s stage ride will always live in my memory—but not for its beauty spots. . . . Leaving Pantano, creeping much of the way, letting the horses walk, through miles of alkali dust that the wheels rolled up in thick clouds of which we received the full benefit, we couldn’t then see much romance in the old stage method of traveling. But the driver said that was his daily job which made us ashamed of our weakness. . . . If it had not been for the long stretches when the horses had to walk, enabling most of us to get out and “foot it” as a relaxation, it seems as if we could never have survived the trip.1

Another stage passenger who arrived at about the same time, Adolphus Noon, wrote to the Chicago Tribune that those destined for Tombstone “can now travel for $4 where they recently had to pay $10. . . . The seventy-five miles are made in about eleven hours—all the glorious effect of free trade and competition, for they formerly took about twenty-four.” Noon seemed as unimpressed by the destination as by the trip. “Tombstone is not a very attractive place,” he recorded. “It is windy and dusty, scantily supplied with water, with no trees to break the landscape . . . yet it will probably be found healthy . . . and good mines and appropriate position will build a town more quickly than sylvan scenes.”2

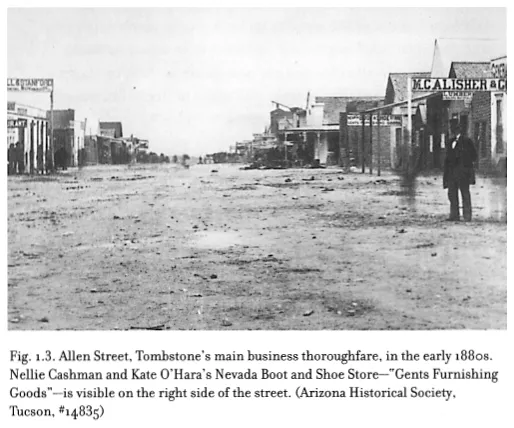

Gray and Noon had come a long way to see this elephant. Located in the arid, hot, and desolate San Pedro River valley in far southeastern Arizona, Tombstone lay about thirty miles north of the Mexican border and deep inside Apache territory. It was the sort of country in which—as one prospector had been warned—a fellow was as likely to find his tombstone as his fortune.

In spite of the dangers, that professional prospector, Edward Schieffelin. persisted with his explorations. He discovered a series of outcroppings of horn silver so rich, it was said, that one could make an impression in the soft metal with a knife or a coin. After making his initial location in September 1877, Schieffelin recruited his brother Al to help prospect and a friend named Richard Gird who agreed to assay the ore samples in return for a one-third interest in the venture. The three men returned to the area in the spring of 1878 and made a series of valuable locations, which they then recorded at Tucson.3

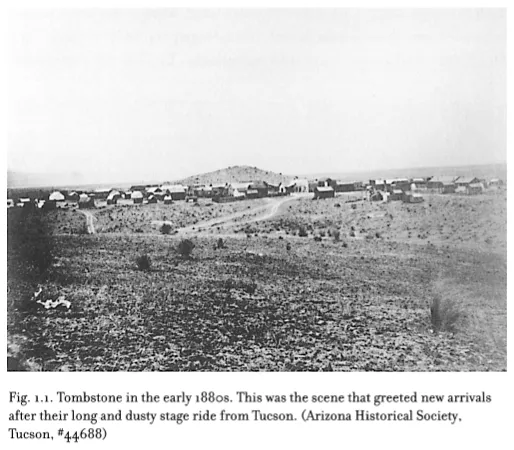

The recording of the locations ended the secrecy that the three had done their best to maintain, and the stampede was on. By the time Gray took his dusty stagecoach ride two years later, Tombstone had a population of more than two thousand, two newspapers, several stage lines and hotels, and many stores and restaurants. By 1882 the population had increased another 200 percent and Tombstone had become the county seat of newly created Cochise County and the preeminent mining camp of the Southwest.

By then the mines had passed out of the control of their original locators. The district included thousands of claims by that time, but its heart consisted of three great mining concerns. The first and arguably foremost of these was the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company, formed out of the original Schieffelins-Gird holdings. Having the claims but needing the capital to develop them, the discoverers brought in a series of investors, including former territorial governor A. P. K. Safford and the Corbin family of Philadelphia.4

In October 1878 the Schieffelins, Gird, and the Safford group reached an agreement, granting the Safford group a one-quarter share in a series of claims in exchange for their construction of a wagon road to the San Pedro River and a ten-stamp mill at the river to process the ores from those claims. This combination of investors organized as the Tombstone Gold and Silver Mill and Mining Company, and their stamp mill, the first in the district, crushed its first ores and shipped its first silver in June 1879. By August the Tombstone Company had produced over ninety thousand dollars in bullion and that month announced its first dividend after fewer than nine months in operation.5

In early 1879 essentially the same parties organized the Corbin Mill and Mining Company out of another set of Schieffelins-Gird claims. In January 1880 the stamps of the Corbin Mill dropped for the first time, and in May of that year the Schieffelin brothers sold their share of the two companies, which were then consolidated as the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company of Hartford, Connecticut. Richard Gird sold out in March 1881. The company had produced more than one million dollars and paid almost a half-million dollars in dividends by that time. By the end of 1881 the company had paid over one million dollars in dividends.6

The Contention claim produced the second great mining concern in the district, nearly the equal of the Tombstone Mill and Mining Company. The Contention claim was originally incorporated as the Western Mining Company in 1880. The Contention had its own mill on order from San Francisco by August 1879 and produced twelve hundred pounds of bullion per week from that mill by the following March. By the end of 1880 production closed in on one million dollars, the company had paid out more than a half-million dollars in dividends, and plans called for a larger mill to handle the mine’s abundant ores. The Western Mining Company combined with several other important properties and was reorganized as the Contention Consolidated Mining Company at the end of 1881.7

The Grand Central Mining Company of Youngstown, Ohio, may be considered the Tombstone District’s third great mining enterprise. This property developed more slowly than either the Tombstone or the Contention. In May 1879 eastern investors purchased the Grand Central properties, clearing the way for “active work on the mine at an early day.” It did not take the Grand Central long to catch up. By the end of 1881 the company had produced over one million dollars in metals and paid out around three hundred thousand dollars in dividends.8

Among them, these three great properties attained almost eleven million dollars in production by the end of 1882. Including the output of the lesser mines of the district, like the Girard, the Head Center, the Vizina, the Bob Ingersoll, and several others, production for the Tombstone District in its first three and one-half years totaled more than twelve and one-half million dollars. Nor did things seem to be slowing down. One source reported that the monthly production average for the district rose in the early part of 1883 over that of the previous year.9

Merchants numbered among the first boomers into the new district, following closely in the wake of prospectors and speculators. They supplied the material needs of this latest bonanza. As early as September 1878, a correspondent to the Arizona Weekly Citizen in Tucson reported that “the new townsite is progressing finely; two stores, one butcher shop and a restaurant under way already.” As the boom days rolled along, Tombstone’s business district grew and evolved. That sole restaurant soon had plenty of competition. Somewhat stunted in growth by a lumber shortage in its earliest days, Tombstone nonetheless saw dozens of business houses being erected toward the end of 1879.10

By mid-1880, the tumultuous bonanza camp had turned into a prosperous town with a bustling business district. “It is a query,” wrote a reporter for the Weekly Citizen,

if there is not a business man to every working miner in the camp. How they all live is a source of wonder to the stranger, and I am not certain that it is not to many of the traders themselves. Of course, some of the merchants here do a princely business, and the town itself is growing rapidly; but so is the business community. On all sides you see new stores in various stages of progress toward completion, and some of the buildings are permanent and handsome structures.11

At the beginning of 1881, a correspondent reported over one hundred business houses in Tombstone, including at least six “doing a very large and profitable business in general merchandise,” along with several stables, two newspapers, and two thriving banks.12

By then business establishments had begun to stratify and diversify to cater to various interests and economic classes. While numerous boardinghouses provided room and board for miners, teamsters, and laborers, those with greater means could eat at the Elite or Maison Doree restaurants, or bed down at the Occidental, Cosmopolitan, or Grand hotels. Specialty stores began to replace the general merchandise houses. Rudolph Cohen turned his general store into a furniture shop, and B. Leventhal turned his into a men’s clothing store. Tasker, Pridham, and Co., general merchants, apparently evolved into the Cochise Hardware and Trading Company. The town also had a foundry to serve its mining industry, and the lumber shortage had been erased by the operation of five sawmills in the mountains surrounding the district.13

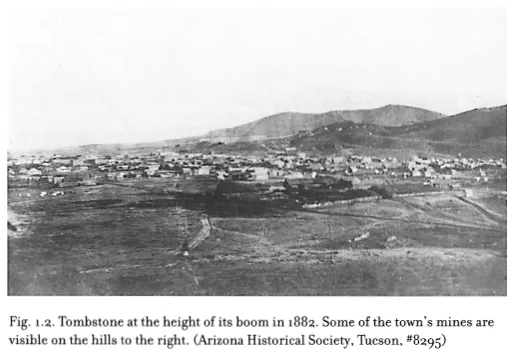

Such business opportunities were not the exclusive domain of American-born men. Irish and German names appeared among the proprietors of hotels and saloons, while some Chinese were involved in the restaurant, laundry, and mercantile trades and others made a living supplying vegetables to the district from gardens along the San Pedro River. Nellie Cashman and Kate O’Hara opened the Nevada Boot and Shoe Store in early 1880, and Cashman and her sister Mrs. Cunningham leased the Russ House Hotel three years later.14

Other women joined Cashman and her partners in operating Tombstone businesses. Some ran small businesses or, like Mary Tack, the Swedish lodging-house keeper, performed domestic services for their mining clientele. Many other women worked at night. A few of these prostitutes have since become part of the legend of Tombstone, but many more lived and worked anonymously in the red-light district along Allen Street. Prostitution, too, was segregated by class, with the most desirable women working at the Bird Cage Theater, a middle class of prostitutes working in the dance halls and saloons, and the lower class working out of cribs in the red-light district. They did not lack for clients among the footloose men who inhabited boomtown Tombstone.15

Those men also had plenty of opportunities to drown their isolation in drink. A correspondent estimated at the end of 1880 that 75 of Tombstone’s 105 business houses were saloons. The following year the town granted 110 liquor licenses, although not all of these were issued to saloons, as liquor could be purchased in some stores. Arthur Laing reported to a Tucson paper in 1881 that “the saloons are in many instances elegantly fitted up, and, in truth, beat anything I have seen in Tucson.” The Alhambra and Oriental saloons were the most luxurious in Tombstone, but other houses catered to working men or ethnic groups.16

In addition to drinking and womanizing, a miner could always squander his earnings at one of the town’s fourteen faro banks or on numerous other games of chance. Describing the saloon trade in nearby Charleston, James Wolf probably spoke for Tombstone as well. “Every saloon,” he recalled, “was sure to have as part of its regular equipment one or more roulette wheels, besides faro and poker tables. These places were open day and night, Sundays and holidays. A few were respectably conducted but the rest were conducted under decidedly more or less flexible codes of ethics. In these places all the games were as crooked as they dared to be.”17

Most of the gambling and much of the solicitation occurred in the saloons, which some observers held to be Tombstone’s most important business activity. When fire demolished the business district in May 1882, “the saloonists” resumed business first. The Weekly Citizen reported that “on the day following the fire some of the most enterprising of them opened out over their smoking ruins. . . . It is reported that one man took in over five hundred dollars the first day, and many others did proportionally well.”18 As long as money flowed in the bonanza camp, the sin businesses would continue to do proportionally well.

Learned professionals headed for the new bonanza along with the gamblers and prostitutes. At the beginning of 1880 a man identified as Retlef reported six or seven doctors and ten lawyers in Tombstone “all trying to eke out a precarious living, your correspondent among the number.” Their ranks included George Goodfellow, formerly an army surgeon at Fort Whipple, in Prescott, Arizona. In September 1880 he resigned his post at Fort Whipple to establish a private practice in Tombstone. The lawyers engaged mostly in mining litigation and real estate deals until the following year, when Cochise County was created and the county seat located at Tombstone.19

True to form in the mining West, a real estate bonanza quickly followed the mineral one. “Town property has a real value now,” a correspondent reported in September 1879, not eighteen months after the initial locations. “Lots are selling from $150 to $250, and corner lots at fancy prices, from $400. The real estate business during the past month has been very brisk.” Almost five months later, another witness confirmed that “lots are held at fabulous prices.”20

The fabulous real estate prices meant high rents. An Arizona Quarterly Illustrated article of July 1880 noted that “the great difficulty here, is to get places to do business in. Small houses are also very scarce and in demand, for small families, and prove profitable investments, as a small plainly furnished two-roomed house rents from $25 up to $40 per month. Board can be had at $8 per week, and good meals at 50 cents each.” More than a year later, the Weekly Citizen reported that “there is not a vacant residence in the city. As soon as the foundations of a new house are laid there are a dozen applicants for it.” Prices for goods were also high.21

Good wages somewhat offset isolated Tombstone’s high rents and prices. The Arizona Quarterly Illustrated article noted that artisans made six dollars a day, miners made four dollars a day, laborers made three dollars a day, and that “house servants [were] very scarce, at high wages.” In this same period, teamsters made two dollars a day and board, and clerks up to three dollars a day and board. As a result, despite its isolation, the Tombstone District prospered. In describing the town at the beginning of 1881, Arthur Laing wrote that “one sees many well-dressed ladies on the streets. Two-horse buggies are not scarce, and the...