eBook - ePub

Howard Hughes

Power, Paranoia, and Palace Intrigue, Revised and Expanded

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This newly revised and expanded edition of Howard Hughes chronicles the life and legacies of one of the most intriguing and accomplished Americans of the twentieth century. Hughes, born into wealth thanks to his father's innovative drill bit that transformed the oil industry, put his inheritance to work in multiple ways, from producing big-budget Hollywood movies to building the world's fastest and largest airplanes. Hughes set air speed records and traveled around the world in record time, earning ticker-tape parades in three cities in 1938. Later, he moved to Las Vegas and invested heavily in casinos. He bought seven resorts, in each case helping to loosen organized crime's grip on Nevada's lifeblood industry.

Although the public viewed Hughes as a heroic and independent-minded trailblazer, behind closed doors he suffered from germophobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and an addiction to painkillers. He became paranoid and reclusive, surrounding himself with a small cadre of loyal caretakers. As executives battled each other over his empire, Hughes' physical and mental health deteriorated to the point where he lost control of his business affairs.

This second edition includes more insider details on Hughes' personal interactions with actresses, journalists, and employees. New chapters provide insights into Hughes's involvement with the mob, his ownership and struggles as the majority shareholder of TWA and the wide-ranging activities of Hughes Aircraft Company, Hughes's critical role in the Glomar Explorer CIA project (a deep-sea drillship platform built to recover the Soviet submarine K-129), and more. Based on in-depth interviews with individuals who knew and worked with Hughes, this fascinating biography provides a colorful and comprehensive look at Hughes—from his life and career to his final years and lasting influence. This penetrating depiction of the man behind the curtain demonstrates Hughes's legacy, and enduring impact on popular culture.

Although the public viewed Hughes as a heroic and independent-minded trailblazer, behind closed doors he suffered from germophobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and an addiction to painkillers. He became paranoid and reclusive, surrounding himself with a small cadre of loyal caretakers. As executives battled each other over his empire, Hughes' physical and mental health deteriorated to the point where he lost control of his business affairs.

This second edition includes more insider details on Hughes' personal interactions with actresses, journalists, and employees. New chapters provide insights into Hughes's involvement with the mob, his ownership and struggles as the majority shareholder of TWA and the wide-ranging activities of Hughes Aircraft Company, Hughes's critical role in the Glomar Explorer CIA project (a deep-sea drillship platform built to recover the Soviet submarine K-129), and more. Based on in-depth interviews with individuals who knew and worked with Hughes, this fascinating biography provides a colorful and comprehensive look at Hughes—from his life and career to his final years and lasting influence. This penetrating depiction of the man behind the curtain demonstrates Hughes's legacy, and enduring impact on popular culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Howard Hughes by Geoff Schumacher in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781948908610Subtopic

North American HistoryPart 1:

Before Las Vegas

1

Young Maverick: Becoming Hughes

Howard Robard Hughes was born in 1905, the same year Las Vegas became a town. But a whole lot would happen to both of them before his life intersected with the city.

Howard is most often associated with Texas, where he was born and where he was buried, as well as California, where he spent the most time during his life. It is often overlooked that he is a progeny of a family, on his father’s side, with deep roots in the Midwest.

After serving in the U.S. Army during the Black Hawk War, Howard’s great-grandfather, Joshua Waters Hughes, settled in southern Illinois. His Army service entitled him to a land grant, which he took advantage of in the form of forty acres in northeast Missouri. He built a log cabin there and lived in it for fifty years.

Howard’s grandfather, Felix Turner Hughes, grew up in that log cabin. He worked as a lawyer (without benefit of a college education) and became solicitor general of the Missouri, Iowa & Nebraska Railroad in Lancaster, Missouri. He married Jean Summerlin Hughes and they had several children, including Howard’s father. In 1880, Felix moved the family to the Mississippi River town of Keokuk, Iowa, where he opened a law firm and was hired as president and general counsel of the Keokuk & Western Railroad. He was elected mayor of Keokuk in 1895.

Felix Hughes championed the idea of damming the Mississippi River at Keokuk to smooth the rapids and generate hydroelectric power. His vision was realized in 1913 with the completion of the dam and powerhouse, which was, at the time, the largest electricity-generating plant in the world. It provided power to Keokuk and other cities across the Midwest. The Lock and Dam No. 19, added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2004, is still in operation today.

Howard’s father, Howard; uncles Rupert and Felix; and aunt, Greta, grew up in Keokuk, in a large red brick house at 312 N. Fifth Street. Howard’s father was known as something of a “mechanical genius,” according to local historian Francis J. Helenthal. Helenthel says he “invented a fire escape for business buildings and a dentist’s drill which was used extensively at the old Keokuk Dental College.”

Howard Sr. studied briefly at Harvard, dropping out after one year, and at the University of Iowa College of Law. He left law school early, but passed the bar exam and started working in his father’s firm. But as he reported back to Harvard years later, he “found the law a too-exacting mistress for a man of my talent, and I quit her between dark and dawn, and have never since been back. I decided to search for my fortune under the surface of the earth.”

Showing an interest in mining, he explored silver in Colorado, zinc in Oklahoma, and lead in Missouri before eventually following the hordes of fortune seekers to Houston, center of the fledgling oil industry.

According to family lore, Howard’s father invented the rotary drill bit that would make him rich while sitting at the dining room table in the family house in Keokuk. The real story is more complicated. Hughes picked up the seed of the idea for the rotary bit from a man named Granville Humason, whom he met in a bar in Shreveport, Louisiana. Hughes Sr. bought Humason’s model for $150. Then Hughes caught a train to Keokuk, where he sought his father’s financial and legal help to secure a patent for the revolutionary drill bit. While there, he sat down at the dining room table and sketched out detailed drawings of the device, as well as technical documents. The patents were granted on August 10, 1909. Howard Jr. was not yet four years old.

When the drill bit made him rich, Howard Sr. built his mother a second house in Keokuk, at 925 Grand Avenue. This was known in the family as the “summer house,” because it offered a view of the Mississippi River and the cool breezes that came with it. Family members recalled episodes when Jean and Felix were not getting along, and Jean occupied the Grand Avenue house while Felix was relegated to the “winter house” on Fifth Street.

Although Howard Jr. was born in Texas, he was baptized in St. John’s Episcopal Church in Keokuk. As a youth, he occasionally visited his grandparents there.

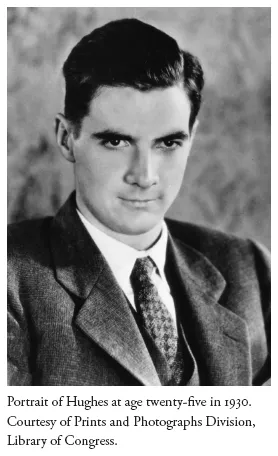

Howard’s mother, Allene Gano, was a Dallas heiress, described by Charles Higham in Howard Hughes: The Secret Life, as “darkly pretty” and “high-strung, a hypochondriac.” The Hughes-Gano marriage—on May 24, 1904, in Dallas—was important enough to be chronicled in the city’s society pages. The young couple settled in Houston, but moved a year later to Humble, a small town northeast of the city, where Howard Jr. was born on Christmas Eve 1905.

In 1907, the family moved to Oil City, Louisiana, outside Shreveport, where Howard Sr. served as postmaster and deputy sheriff while chasing his oil dreams. A year later Howard Sr. pursued the invention that would make him rich. He purchased two patents for drill bits, one for $2,500, the other for $9,000. Working with partner Walter Sharp, he tested, experimented, and eventually invented the Hughes drill bit. Hughes and Sharp started the Sharp-Hughes Tool Company. When Sharp died in 1912, Hughes bought out his interest in the company. This clever piece of hardware became the foundation of the family fortune.

What made the Hughes drill bit so innovative? As the oil business started taking off in Texas just after the turn of the century, miners were having trouble drilling through underground rock. The bits then in use scraped their way through the rock and wore out quickly. The Hughes drill bit had two rotating steel cones that cut through rock much more efficiently. Oil companies wanted the Hughes drill bit because it cut a ton of time out of the drilling process, and they could go deeper into the earth in search of oil than ever before. It wasn’t long before the Hughes drill bit became the industry standard.

The family did not enjoy the riches of its drill bit fortune right away, in part because Howard Sr. spent much of his income on gambling and expensive equipment. But by 1913, the Hughes fortune had solidified. The family moved into a pricey apartment and became part of Houston’s country club set.

Their child, nicknamed Sonny, started out life as a sickly boy, partly a result of his mother’s hypochondria. But several summers at Camp Dan Beard in Pennsylvania bolstered his fitness and taught him to appreciate nature and to learn the ins and outs of woodcraft. He also briefly excelled at the private Fessenden School, near Boston, where he edited the school paper, learned to play golf, and played saxophone in the school band.

Hughes’ parents began to spend more time in Southern California. They purchased a home on Coronado Island, near San Diego, and in 1921 Sonny transferred to the Thacher School in Ojai, where he excelled in math and science and rode horses. During summer vacation, Hughes spent time with his uncle, Rupert Hughes, a best-selling novelist and screenwriter who exposed the teenager to the movie business.

Multiple tragedies struck the family about this time. In 1922, Hughes’ mother, hemorrhaging from her womb, died in a Houston hospital while receiving anesthesia. She was thirty-eight. A year later, Hughes’ Aunt Adelaide, Rupert’s wife, hanged herself during a trip to Asia. Finally, in 1924, Howard Sr. died of an embolism at his office in Houston. He was fifty-four.

Hughes had withdrawn from the Thacher School and was attending the California Institute of Technology when the devastating trio of deaths hit his family. But rather than falling apart, the eighteen-year-old decided to take control of his father’s company. To accomplish this, he had to pay off his father’s considerable debts and fend off an attempt by his uncle to run the show.

Helping to establish his maturity to run his father’s affairs, in 1925 Hughes wedded a childhood friend, Ella Rice, a member of the oil family for which Rice University is named. But after the newlyweds moved to Los Angeles later that year, the marriage gradually collapsed. Hughes’ obsession with business and golf left his wife out in the cold, and she found little comfort from Hollywood society. Hughes’ infidelity with the actress Billie Dove was a contributing factor in Ella’s return to Houston in 1928. They divorced the following year.

The filmmaker

Hughes moved to Southern California to break into the movie business. His first venture was Swell Hogan, starring Ralph Graves, a friend of Hughes’ father. Hughes, a novice producer, trusted Graves, a veteran actor, to direct the film, and this proved to be a mistake. “It was rubbish,” wrote Tony Thomas in Howard Hughes in Hollywood. “It had no structure, no plot, no tension, and the acting was ludicrous. Hughes ordered the film to be placed in a vault, from which it never emerged.”

The Swell Hogan disaster changed Hughes’ approach. He studied every aspect of moviemaking and become a more careful judge of talent. His next project was called Everybody’s Acting. Hughes hired proven talent to write and direct the film, and after he secured a distribution deal with Paramount, the movie was financially successful in 1926.

After starting his own movie company, Caddo Productions, Hughes hired Lewis Milestone to direct his next project, a World War I comedy called Two Arabian Knights. With a large budget, a good script, and Milestone’s expert direction, Two Arabian Knights was a hit with moviegoers and critics. The film, released in 1927, earned a Best Director honor for Milestone at the first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929. (Three decades later, Milestone directed Ocean’s Eleven, a film with legendary connections to Las Vegas.)

With just three movies under his belt and barely twenty-two years old, Hughes had nonetheless earned a measure of respect in Hollywood. Now he was eager to rise to the top of the heap with his next film. Hughes was fascinated by aviation and wanted to merge that interest with filmmaking. When he came across the World War I story of Hell’s Angels, he saw the perfect opportunity.

Unlike his previous films, Hughes decided to become intimately involved in the production of Hell’s Angels. With Hughes hovering relentlessly, original director Marshall Neilan quit after a few weeks. When the second director, Luther Reed, departed after two months, Hughes decided to direct the picture himself.

This proved to be a costly and time-consuming decision. Hughes labored over every detail, constantly making changes to the script and camera angles. This, along with the long hours Hughes demanded on the set, strained the cast and crew. “He could work for twenty and thirty hours at a stretch, and he seemed to show little regard for the more regular time schedules of other people,” according to author Tony Thomas. “He never wore a watch and he appeared to be oblivious of time.”

Hughes bought dozens of airplanes to be used in the film’s aerial combat sequences. It was dubbed the largest private air force in the world. He also purchased and leased real estate across Southern California to stage the ground scenes.

Instead of using military airplanes and pilots, as had been done in the 1927 epic Wings, Hughes hired stunt pilots because he thought they were more capable of performing the dramatic maneuvers he wanted to film. But Hughes’ demand for dangerous stunts took its toll on the airplanes and the pilots. Four men—three pilots and a mechanic—died in flying accidents during the filming.

The first of Hughes’ many flying accidents occurred during the filming of Hell’s Angels. Trying an unadvised maneuver in a Thomas Morse Scout, Hughes crashed. Pulled from the wreckage, he was in the hospital for a week.

Shooting began in the fall of 1927, and continued through 1928 and 1929. When Hughes was frustrated by the absence of clouds in the Southern California skies, he picked up the giant production and moved it to the Oakland Airport in Northern California, where there was more reliable cloud cover.

While Hell’s Angels was in production, Hughes released two other films in 1928: The Racket, a gangster flick directed by Milestone, and The Mating Call, starring the French actress Renée Adorée. The Racket was a critical success, and The Mating Call was a popular success, especially because of its steamy sexual undercurrents. Hughes had become a force in the silent film era.

But he also was something of a victim of the switch to talking pictures. Midway through production on Hell’s Angels, Hughes decided it needed to become a talkie. He brought in new actors (including a teenage Jean Harlow to replace the heavily accented Swedish actress Greta Nissen) and reshot dramatic scenes.

Hughes orchestrated a grand premiere for Hell’s Angels on May 27, 1930. Fifty airplanes flew in formation over Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood. Thousands of people crowded onto closed-off Hollywood Boulevard to watch celebrities arrive by limousine. Hughes attended the event alongside Dove. While the movie’s dialogue and plot lines did not impress critics, the aerial battles left them breathless. The critic for The New York Times called it “a strange combination of brilliance and banality.”

Film historian Thomas, writing in 1985, argued that Hughes deserves a place of honor in movie history if only for the astonishing battle scene between Allied and German fighter pilots. “The dogfight between the fighter pilots, involving thirty planes, not only was the most astonishing aerial warfare filmed to that time, but nothing done since has surpassed it. . . . His pilots and photographers achieved a breathtaking sequence, with the planes ferociously attacking each other like angry hornets, zipping, swooping, looping, and tumbling.”

The movie was a huge hit across the country and in England, but it did not earn more than its $4 million price tag. Hughes opted for more modest budgets for subsequent movie projects.

Hughes’ affair with Dove prompted him to sign her to a contract and to produce The Age for Love, which Hughes hoped would reignite her career. Instead, the 1931 drama was a dismal failure. Hughes arranged for Dove to receive flying lessons and she earned her pilot’s license, after which she starred in the World War I film Cock of the Air. The film received tepid reviews, and moviegoers were disappointed there weren’t more flying scenes.

Dove was under contract to do five movies for Hughes, but when their relationship disintegrated, she wanted to terminate her contract. Dove retired from acting after just one more film.

Pressing on, Hughes produced Sky Devils, another World War I flying movie, this one starring a young Spencer Tracy. Despite using aerial footage left over from Hell’s Angels, the film was another dud.

Three straight failures suggested to Hollywood observers that Hughes had lost his touch, but Hughes still had a couple of celluloid gems in the works. The Front Page, a rapid-fire comedic dissection of the newspaper business, written by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, was a wildly successful Broadway play in 1928. Hughes bought the rights to bring it to the silver screen and hired Milestone, who had by now won a second Oscar, to direct. The com...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface: The Hughes–Las Vegas Connection

- Part One: Before Las Vegas

- Part Two: Las Vegas

- Part Three: After Death

- Part Four: Industry

- Part Five: People

- Part Six: Hughes in Pop Culture

- Acknowledgments

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author