![]()

1

OPENING SALOON DOORS

Archaeology Unearths the Real Mother Lode

At the beginning of the 1993 film Tombstone, a narrator notes that the murder rate in the sparsely populated “frontier West” was higher than anywhere else in the United States, including New York City. A few minutes later, the scene pans to Tombstone, Arizona, shown as a dusty western boomtown with false-front mercantile buildings. The panorama effectively displays the juxtaposition of finely dressed ladies and gentlemen against the backdrop of grit and desert. A Chinese immigrant hustles among the crowd, a testament to the filmmaker's historical research. In the foreground, Wyatt Earp—played by Kurt Russell—chats with his brothers and a sheriff about saloons. During their conversation, these drinking establishments are described as “the real mother lode” in the growing community. While the filmmakers demonstrate their attention to historical accuracy by including this poignant statement about the significance of saloons, they clearly could not resist the more popular, sensational caricature of these businesses, for the scene closes with the sound of gunfire and a group of grimy men tumbling onto the street from a saloon. Tombstone provides an example of the ways in which the western film genre links violence with saloons. Admittedly, films and television programs have created national representations of “the West,” with popular, sensationalized depictions elevating the saloon to its status as a place of hostility and as a conveyor of Americana.

The popularity of television shows such as Gunsmoke and Bonanza brought western saloons into American households at least once a week between the 1950s and the 1970s, enhancing the widespread mythic notoriety of these public drinking places. For example, in any given Bonanza episode, characters inevitably ran into some sort of trouble while sidling up to the bar in establishments such as the Silver Dollar, Julia's Palace, or the Bucket of Blood Saloon. Fictitiously set in Virginia City, Nevada, this popular series revived the public's fascination with this northern Nevada mining town.1

Modern dramatizations, such as those of the Bonanza episodes, conveniently coincide with historical accounts of saloons in Virginia City. The original boomtown provided its own backdrop for sensational portrayals of these businesses as early as the 1860s. At that time, Samuel Clemens lived in Virginia City. He and other writers such as William Wright took pen names, such as Mark Twain and Dan DeQuille, and wrote vibrant accounts of saloon shenanigans.2 Journalist J. Ross Browne published illustrations, such as “Home for the Boys,” in prominent magazines like Harper's Weekly and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper (figure 1.1).3 The images depicted by people like Browne and Twain became many people's first impression of western saloons, influencing the violent imagery that brought about later, far-fetched treatments of this social institution.

Brimming with fortune and excitement in 1865, Virginia City provided ample fodder for these writers and journalists. Gold and silver mines yielded enough wealth to transform a camp of scattered tents into a booming city on a rugged mountain slope. Ornate brick buildings and row houses made the place look like San Francisco, while carriages, stagecoaches, pedestrians, horses, oxen, dogs, and even camels filled the dusty streets with a throng of traffic, a clamor of sound, and an overwhelming mix of odors. People going about their business came from all over the world, and street chatter included many foreign languages and heavy accents.

The businesses that lined the bustling cosmopolitan city center included general stores, apothecaries, butcher shops, tailors, boardinghouses, hotels, bowling alleys, and saloons. Saloons were quite common on Virginia City's sprawling urban landscape, and they usually outnumbered all other retail establishments in mining boomtowns. Eliot Lord's estimation of more than a hundred saloons operating in and around Virginia City during the 1870s strongly suggests that they likely outnumbered many other business enterprises in that community as well.4

Numerous advertisements in contemporary newspapers portray the assortment of saloons, including those that offered customers billiards, Havana cigars, female entertainment, dancing, coffee, cockfights, dogfights, and a range of alcoholic beverages.5 This variety suggests several things. First, it indicates that sensational period depictions were based on the sheer abundance of such drinking establishments. Second, shrewd entrepreneurs were trying to fill niches in a saturated boomtown industry. Third, there was a market for a range of businesses devoted to serving the population's need for recreation and leisure. Well-paid miners worked hard underground during eight-hour shifts.6 They tended to have disposable income, and because of a shorter-than-usual workday, they had free time, especially during mining bonanzas. Saloons served as places where they could while away free time and spend money.

As boomtowns such as Virginia City expanded and became internationally famous, more people arrived from all over the world, amplifying the cultural and ethnic diversity of these communities.7 Well-established cities therefore supported saloons that filled additional entertainment niches by catering to specific ethnic affiliations. Saloons came to reflect the diversity of these and other urban American centers more than any other social institution. As the diversity of the people increased, so did the need for drinking houses to cater to each group.8

Upon arrival in the region's bustling boomtowns, immigrants frequently found a foreign and often hostile environment. The diversity of the people living, working, and socializing in such surroundings meant that the settings could be both intimidating and confusing.9 Saloons owned by a specific ethnic or cultural group accommodated customers of similar backgrounds and provided places of refuge and solidarity. Although some ethnic groups identified themselves according to places of drink, this was not always the case. For example, even though some Irish establishments in places like Virginia City did not welcome outsiders, other Irish saloonkeepers sought as large a customer base as possible. Another example of diversity was that of a German beer garden in Virginia City, designed by an American-born man named van Bokkelin, who welcomed customers from a broad segment of the community.10

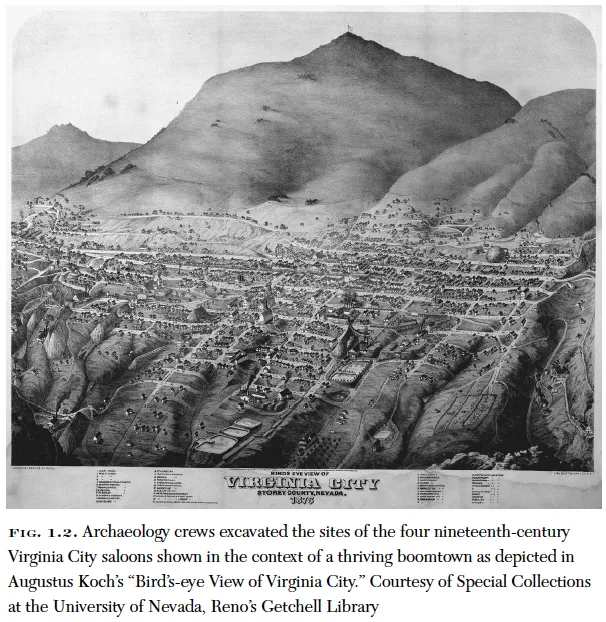

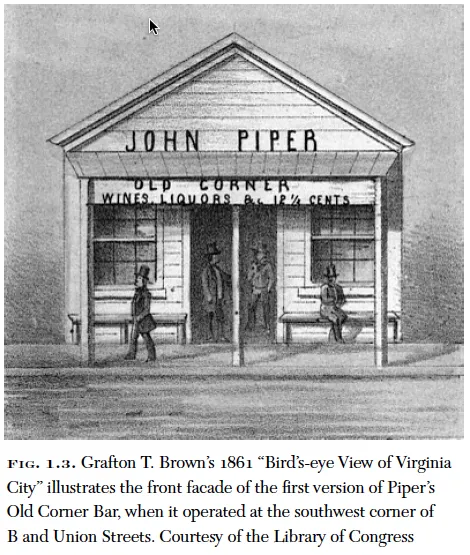

Amid this varied collection of saloons, archaeologists have explored—and virtually opened the doors to—four public drinking establishments that served relatively distinct groups in Virginia City (figure 1.2). The first, Piper's Old Corner Bar, operated between the 1860s and 1880s in the heart of the city's commercial corridor. A German immigrant, owner John Piper opened his business for a range of European immigrants and European Americans. As early as 1861, this saloon operated in a small wooden structure at the southwest corner of B and Union Streets (figure 1.3). In 1863 John Piper built a two-story fireproof brick building across the street, at the northwest corner of B and Union Streets, and it became known as the Piper Business Block. Piper moved the Old Corner Bar to the lower story of that building and rented out the second story as office space. By 1877 Piper remodeled the business block to become the front section of his newly constructed Piper's Opera House.11 The opera house had previously operated at another location two blocks downslope from the Piper Business Block, near the corner of D and Union Streets.

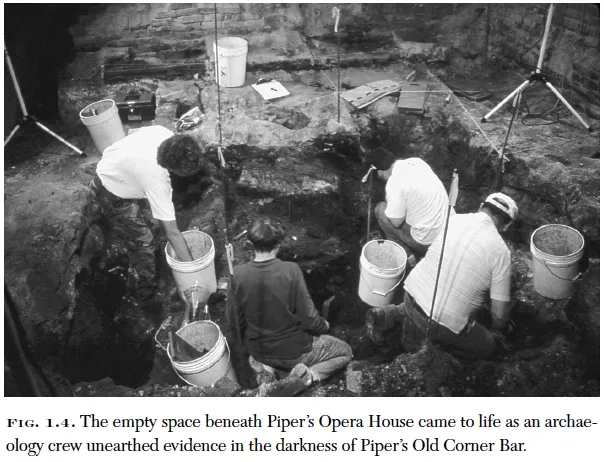

Despite the fact that a massive opera house auditorium loomed behind the transformed business block, John Piper still operated his Old Corner Bar from the first story of that building (see figure 2.2). At this time the Old Corner Bar became known as the “theatre saloon,” catering to a theatergoing clientele and sporting an upscale atmosphere. The opera house and its saloon thrived as tandem entertainment venues until 1883, when a devastating fire destroyed the auditorium and cleared away the contents of the brick business block.12 Piper reconstructed the opera house auditorium by 1885, but there is no mention of his reopening the Old Corner Bar at that time.13 Nevertheless, the outer shell of the brick business block survived the fire of 1883, and the space still housed the charred remains of the Old Corner Bar even after the new opera house rose from the ashes of the old one. Archaeological remains of the Old Corner Bar's 1863–1883 operations lay protected within the rubble of the burned-out shell of the empty saloon space, thus creating a unique archaeological site within a standing structure (figure 1.4).

Piper's Old Corner Bar and Piper's Opera House are relatively well documented in historical records, especially newspapers. These sources help to chronicle the history of the theatre saloon in Virginia City. Documentary evidence about other saloons, however, is not so abundant, and consequently the historical overviews of those establishments are notably shorter.

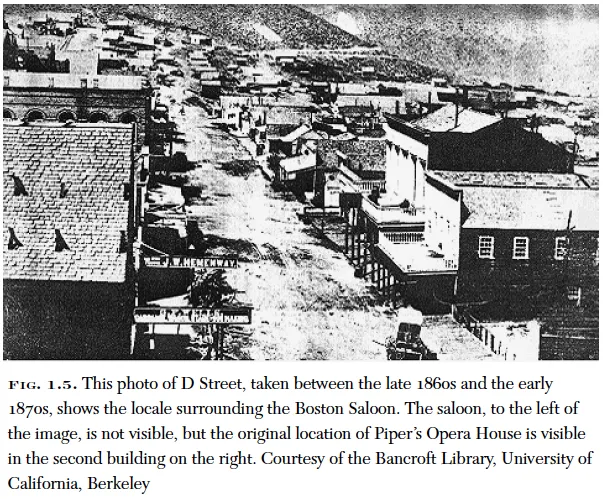

For example, much less is known about the story of the Boston Saloon. William A. G. Brown, an African American from Massachusetts, owned the establishment and welcomed a clientele who had African ancestry. Brown arrived in Virginia City by 1863, at which time he worked as a “bootblack,” a term used for a street shoe polisher. By 1864 he founded the Boston Saloon on B Street, an upslope location along Virginia City's mountainside setting and well beyond the center of town. Sometime between 1864 and 1866, Brown moved his business from that location to the southwest corner of D and Union Streets (figure 1.5),14 in the heart of Virginia City's commercial corridor and entertainment district. Brown operated the Boston Saloon on that bustling corner until 1875, at which time the establishment disappeared from historical records.

Sources described the Boston Saloon as “the popular resort of many of the colored population,” and African American writers lamented the loss of “a place of recreation of our own” in Virginia City after the establishment closed.15 The wording in the sources noted above suggests that the Boston Saloon was primarily for people of African background, and it is quite likely that the drinking house served various socioeconomic segments of that group.

O'Brien and Costello's Saloon and Shooting Gallery operated during the 1870s in the center of the Barbary Coast, a place known for its cribs, brothels, rough saloons, and danger.16 Owned by men with Irish names, this saloon catered to a primarily Irish clientele, but very likely served other groups as well. While many Irish-owned saloons in other U.S. cities specifically accommodated the Irish, others were more assimilated and sought general patronage.17 The Shooting Gallery's location in the disreputable Barbary Coast area also suggests that its patrons had little socioeconomic power.

The Hibernia Brewery operated around 1880 just outside the Barbary Coast. This location was about 200 yards from the center of Virginia City's dense commercial district. Typical of the Shooting Gallery and other plebeian establishments situated along the outskirts of the city's commercial corridor, the Hibernia welcomed Virginia City's Irish immigrants and Irish Americans. The Hibernia was owned by two men, Shanahan and O'Connor, whose names evoke Irish ethnicity.18 The partnership of these two men, like that of O'Brien and Costello, probably allowed the two Irish-owned saloons to stay open all night as the associates in each drinking house shared shifts to cater to the boomtown's twenty-four-hour schedule.19

The two Barbary Coast saloons represent the more rustic establishments on the wide-ranging scale of Virginia City saloons. Piper's Old Corner Bar, on the other hand, with its theatergoing clientele, was fancier. Together with Piper's Opera House, this upscale entertainment venue was a good example of Virginia City's transition to a permanent and successful community.20 The Boston Saloon operated a few blocks downslope from Piper's Old Corner Bar. It was unusual that the Boston Saloon's proprietor was African American, for typical saloon owners were white men in their thirties.21 That the Boston Saloon primarily accommodated an African American clientele provides another level of insight into the intricacies that existed among Virginia City's boomtown saloons.

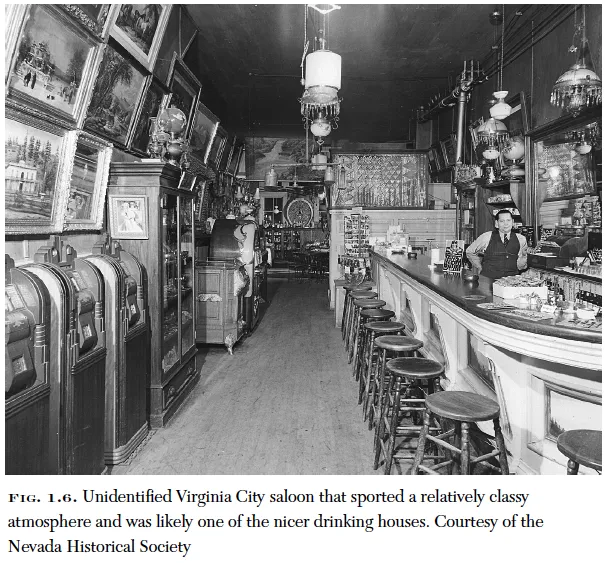

The mere existence of such a diverse range of establishments draws attention to the variety of businesses and people making up the backdrop of mining boomtowns and provides a contrast to the one-dimensional saloon imagery supplied by Hollywood depictions. Historical records portray the more authentic assortment of saloons, with some described as “spacious rooms furnished with walnut counters, massive mirrors, and glittering rows of decanters” while other are characterized as consisting of no more than a “cheap pine bar with its few black bottles.”22 Virginia City's diverse population made for ample clientele to support both the classier establishments and the more sordid ones (figure 1.6).23

Together, historical and archaeological records make it possible to go back in time and walk into those establishments. Primary sources aid such reconstructions. Eliot Lord's Comstock Mining and Miners (1880), William Wright's The Big Bonanza (1876), and nineteenth-century newspapers such as the Territorial Enterprise, along with the satirical depictions in Mark Twain's Roughing It (1873), are among the records of Virginia City's past written by people who experienced its nineteenth-century mining bonanza. Twain's accounts are certainly fanciful and portray a rather notorious tenure in Virginia City. Twain, like later movies, popularized and mystified the so-called “wildness” of the West. Nevertheless, since he resided in Virginia City during the early 1860s, his descriptions can be used as a type of primary source.

When he was still using the name Samuel Clemens, Twain accompanied his brother, Orion, to Nevada Territory in 1861. Rewarded for supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election, Orion Clemens received an appointment to serve as secretary to Nevada's territorial governor. Sam Clemens traveled with his brother under the title “secretary to the Secretary.”24 Although he never really held that position because of lack of funding, the younger Clemens remained in the region for nearly three years, joining the staff of Virginia City's Territorial Enterprise in 1862. Clemens first used the pseudonym “Mark Twain” in 1863, while he was living in Virginia City.25

In addition to primary sources, secondary historical literature, such as the work of Ronald M. James, provides an impressive collection of information about the history of Virginia City. Using statistical data compiled from a wide range of historical records, James assembled an account of nineteenth- and twentieth-century life in this boomtown, presenting a glimpse of its social setting and creating a foundation for understanding the context of saloons in that place.

James teamed up with archaeologists such as Don Hardesty to discover materials associated with the ruins of saloons. Realizing that authentic renderings of saloons had long been clouded—and nearly lost—by popular accounts, these history and archaeology teams were eager to investigate primary historical documents and to sink their trowels into the earth to learn more about these icons of Americana.

...