eBook - ePub

The River and the Railroad

An Archaeological History of Reno

Mary Ringhoff, Edward Stoner

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The River and the Railroad

An Archaeological History of Reno

Mary Ringhoff, Edward Stoner

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

When the City of Reno decided at the beginning of this century to create a trench to lower the railroad tracks that ran through its center, archaeologists associated with the ReTRAC (Reno Transportation Rail Access Corridor) project had a unique opportunity to explore the evidence of thousands of years of human history locked beneath downtown's busy streets. The River and the Railroad traces the people and events that shaped the city, incorporating archaeological findings to add a more tangible physical dimension to the known history. It offers fascinating insights into the lives of many different people from Reno's past and helps to correct some common misperceptions about the history of the American West.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The River and the Railroad an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The River and the Railroad by Mary Ringhoff, Edward Stoner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of Reno

The first people to arrive in what would become Reno were not the fur trappers, surveyors, or emigrants of the 1840s, but hunter-gatherers who explored the valley thousands of years before that. At the western edge of the Great Basin, the river-fed, grassy valley that would later become known as the Truckee Meadows played host to migrating waterfowl, abundant animal life, and, probably, prehistoric people. Although no evidence for these early inhabitants has yet been discovered, the presence of Clovis points in Washoe Valley, about twenty miles to the south, indicates that people were probably in the Truckee Meadows by about 12,000 years ago.

Archaeologists divide prehistory into periods in order to compare prehistoric cultures from different eras. Interpretation and understanding of the cultural variability within the western Great Basin and Sierra Nevada is likewise informed by partitioning broad aspects of that variability into prehistoric components, or phases. Archaeologists Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips defined “phase” as “an archaeological unit possessing traits sufficiently characteristic to distinguish it from all other units similarly conceived, whether of the same or other cultures or civilizations, spatially limited to the order of magnitude of a locality or region and chronologically limited to a relatively brief interval of time.”1

The time periods that units encompass are somewhat arbitrary and are constantly being revised as new information is discovered. They are also regionally dependent; the chronology for the Eastern Sierra Front, the area in which Reno is located, is different from chronologies in other parts of the Great Basin.

Archaeologists divide prehistory not only by phase, but also by adaptive strategy—what people did in a certain time period to adapt to changing environmental conditions. For the western Great Basin and the Eastern Sierra Front, these adaptive strategies fall into four periods: the Paleoarchaic, the Early Archaic, the Middle Archaic, and the Late Archaic.

| Chronology of the Eastern Sierra Front |

The date ranges below are based on calibrated radiocarbon years and are expressed as years before present (BP) or years ago for the sake of editorial simplicity.

| Climatic Periods and Geological Events |

| 10,500 | Pleistocene epoch and last ice age end and the Early Holocene begins; modern climates appear. |

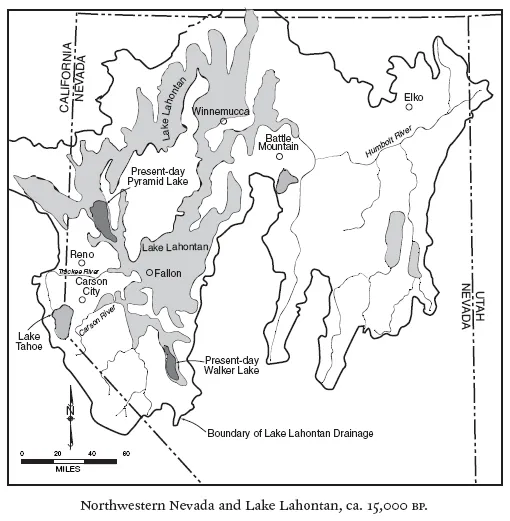

| 10,500–7500 | Early Holocene: Climate warms and Pleistocene lakes such as pluvial Lake Lahontan diminish. |

| 7600 | Mount Mazama erupts, resulting in the Crater Lake caldera. Ash fall mantles much of the Great Basin. Volcanic ash washes from the slopes of Peavine Mountain and is redeposited on the Truckee River floodplain. |

| 7500–3500 | Middle Holocene: Global climate warms, resulting in droughts of varying length and intensity in the Great Basin. |

| 3500–present | Late Holocene: Climate becomes cooler and wetter with a gradual transition to modern climate. |

| 500–100 | Little Ice Age: Climate cools; alpine glaciers resurge. |

| 100–present | Climate becomes warmer and drier. |

| Cultural Periods and Phases |

| 10,000–8000 | Paleoarchaic period/Tahoe Reach phase: Peopling of the western Great Basin and Eastern Sierra Front; artifacts include large stemmed (Great Basin Stemmed) projectile points. |

| 8,000–4000 | Early Archaic period/Spooner phase: Artifacts include large side-notched and possibly Humboldt lanceolate projectile points. |

| 5000–3000 | Middle Archaic period/Early Martis phase: Artifacts include contracting stem points of the Elko-Martis series and Steamboat projectile points (dart points thrown using a spear thrower or atlatl), and large basalt bifaces. |

| 3000–1300 | Middle Archaic period/Late Martis phase: Artifacts include corner-notched and eared points of the Martis and Elko series; large basalt bifaces; and semisubterranean houses with internal storage pits. |

| 1300–700 | Late Archaic period/Early Kings Beach phase: Artifacts include Rosegate series projectile points (arrow tips); chert cores; bow and arrow technology; flakes and other small chert tools, and hullers utilized; house pits may be small, shallow, and saucer-shaped. |

| 700–150 | Late Archaic period/Late Kings Beach phase: Artifacts include Desert series projectile points; chert cores; flakes and other small chert tools utilized; house pits are shallow, saucer-shaped. |

The Paleoarchaic period in the Eastern Sierra Front occurred between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago and includes the Tahoe Reach phase of the eastern Sierra Nevada. The climate was becoming warmer and more arid then, and the great Pleistocene lakes were drying up. People presumably hunted big game as well as smaller animals, and consumed easily gathered and processed lake and marsh plants. Unlike the Archaic cultures to come, they did not grind seeds or live on sites long enough to accumulate midden or trash deposits; nor did they construct permanent structures or store resources.

The Early Archaic for the area is dated between 8,000 and 4,000 years ago and includes the Spooner phase. The warming trend continued during this period, and big game hunting remained a major focus of subsistence. The climate continued to warm and was characterized by droughts of varying length and intensity. People used grinding stones to process seeds, and used caves and rock shelters to store their goods and tools. Population numbers were low, and sites, including habitation areas, tended to be located on valley bottoms near permanent streams, but the uplands were also used.

The Middle Archaic spanned the time from 5,000 to 1,300 years ago and includes the Early and Late Martis phases of the eastern Sierra Nevada. The climate was cooler and moister than in the previous period, and Lake Tahoe overflowed its natural sill. Hunting had become more important, and hunters using atlatls (spear throwers) and dart points went out from base camps located on valley margins. People placed their base camps in areas with multiple resources, including hot springs and tool stone sources. A number of known sites from this period contain substantial winter pit houses with hearths and cache pits.

Archaeologist Robert Elston proposed a basic Archaic settlement pattern for the Great Basin, with two alternate variations: a dispersed pattern and a restricted pattern.2 The former was the typical pattern in the more arid regions of the western Great Basin subarea, which includes central Nevada; small residential groups frequently selected different winter and base camp sites from year to year to take full advantage of relatively unpredictable and scarce basic resources such as food and water. The restricted pattern prevailed throughout the Eastern Sierra Front, including the Truckee Meadows, between 4,000 and 2,000 years ago. At that time the climate was wetter and provided a resource base that was more reliable and abundant in relation to population density. In the Middle Archaic Martis phase, residential groups could regularly occupy optimally located sites, or “sweet spots,” with easy access to a wide range of needed supplies. Thus, they could procure valuable resources such as large game at low cost, with few residential moves.3

The Late Archaic began about 1,300 years ago and lasted until shortly after contact with European Americans. The climate was drying again, and subsistence was based on seeds, fishing, and small game. The atlatl and dart were replaced by the bow and arrow, and flaked stone technology became more simplified. Houses became smaller and less complex and were built in shallow basins lacking internal cache pits.

The Kings Beach phase of the Late Archaic featured a more dispersed settlement pattern with less regular occupation of optimal sites.4 This pattern was linked to a changing set of subsistence strategies characterized by people using progressively more diverse resources with greater intensity and exploiting a greater number of ecological zones. Groups continued to occupy the old sites but began also to occupy new sites in less optimal locations,5 either because resources were being depleted faster at the old sites, necessitating more frequent moves, or because a growing population filled in the spaces between optimal locations.

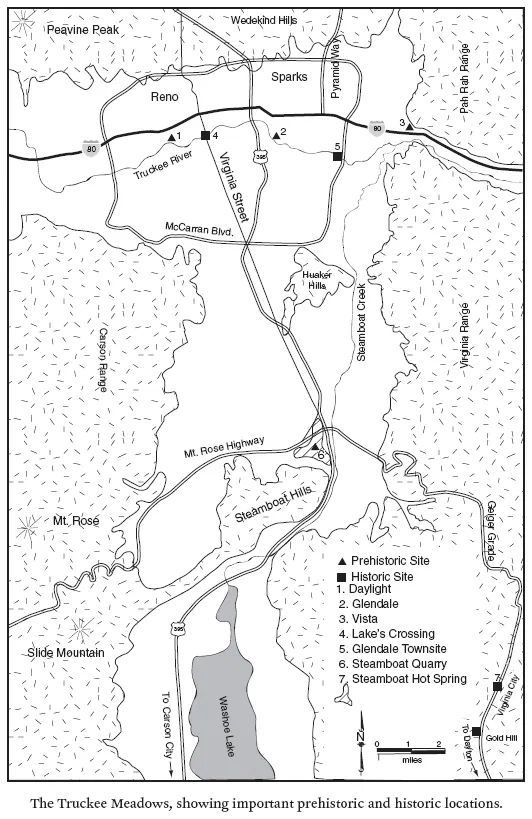

The Truckee Meadows is located within traditional Washoe territory. In recent times the region was used by both Washoe and Northern Paiute groups. The Hokan-speaking Washoe lived primarily in valleys along the eastern Sierra slope and in the Lake Tahoe vicinity. Lake Tahoe is central to the Washoe territory, and groups from around the region spent summers there. The Washoe seasonal range extended as far north as Honey Lake Valley and as far south as Topaz Lake. The Washoe are believed to have occupied their present range for about five thousand years. Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber estimated the full strength of the tribe to have been approximately 1,500 at the time of contact in the early 1840s; the estimate was 900 in 1859.6

The Northern Paiute, or Paviotso, occupied a larger area estimated to cover a third of present-day Nevada as well as southeastern Oregon, southern Idaho, and eastern California.7 Although not all researchers agree, linguistic evidence indicates the Numic-speaking Paiute entered the Great Basin approximately one thousand to two thousand years ago.8

Historical accounts allude to interactions between the two groups. Local writer Grace Dangberg noted that in 1863, Paiute and Washoe mixed in Antelope Valley (south of Gardnerville, about fifty miles south of Reno).9 Frank Morgan, a Washoe consultant, reported confrontations between Washoe and Paiute Indians near McTarnahan Bridge, on the East Fork of the Carson River south of Carson City.10 This area, referred to as “Coyote Smokeout,” was known for its abundant freshwater mussels and as a good source of quartz, and is the location of many Washoe legends. According to Dangberg, the Washoe were sometimes intimidated by their neighbors to the east; the Northern Paiute would not let them own horses, for example.11

Despite numerous accounts of friction, however, the two groups often had peaceable relations and intermarried. A Paiute consultant reported to ethnographer Willard Z. Park that the Washoe often traveled to Pyramid Lake in Paiute territory and were referred to as cousins.12 In 1917 the federal government established the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony in a twenty-eight-acre tract that housed the Paiute tribe in the northern part and the Washoe in the south. A history of the Washoe tribe reports that the Numa and Washoe participated in intertribal hand games that offered social as well as competitive opportunities. One elderly Numa remembered them: “The Washo gamblers were mostly young men, and they would come over on the Paiute side of the colony to challenge the Paiute gamblers, who were mostly older women.”13

Archaeologists studying Washoe sites have noted a low frequency of trade items such as obsidian from north and east of Washoe territory, but ample evidence of trade with Sierran and trans-Sierran groups.14 The material record suggests more extensive trade between the Washoe and their southern and western (Sierran) neighbors than with the Northern Paiute.

In the vicinity of Reno, the Washoe once lived north of downtown near the future sites of the University of Nevada and the original Manogue High School campus, near Idlewild Park, and in several areas along the Truckee River.15 In the Truckee Meadows, large archaeological sites have been located at Vista in eastern Sparks, Glendale, Huffaker Hills, the Mount Rose Fan, and near the sloughs in the former Double Diamond Ranch in the heart of the Truckee Meadows.

Fish was an important part of the diet of these groups, who used fishing platforms, dip nets, spears, and harpoons along the banks of Great Basin rivers.16 Northern Paiute people living along the Truckee and Walker rivers set cone-shaped traps in willow weirs and placed minnow-catching basketry traps in shallow water. The 1852 diary of Mariett Foster Cummings provides a good description of Paiute line and hook fishing on the Truckee River in August: “They procured for me great numbers of little fish resembling a sardine which they caught with ingenious little hooks made of a little stick one fourth of an inch in length to which was fastened nearly at a right angle a little thorn. These were baited with the outside of an insect. The line was simply a linen thread with six of these hooks attached.”17

Pine nuts were also an important staple for both the Washoe and Northern Paiute people. This nutritious resource was easily stored and was a mainstay during the winter months. In this region, pinyon pine trees grow only south of the Truckee and Humboldt rivers and east of the Sierra Nevada; near Reno, they grow in the Virginia Range. The Washoe, who were more closely tied to the resources of the Sierras, also relied on acorns and sometimes traded them. Although Pyramid Lake people gathered acorns south of Honey Lake, it is doubtful that they regularly consumed them.18

Pine nuts were more than just a nutritious meal; the pine nut harvest in the early fall was and is an integral part of the cultural and social lives of local groups.19 Willard Z. Park’s consultants reported that the Washoe usually harvested the west side of the Pinenut Mountains while the Paiute exploited the eastern slopes.20 Hank Pete, a Washoe informant for anthropologists Stanley and Ruth Freed, noted that it was the task of one particular man to dream about pine nuts and pray that they would increase in number and not be full of worms.21 Although he was not a shaman, this man had power and was the leader of the pine nut dance; he decided when the nuts were ready for picking. As part of the routine, a headman traveled to the hills to assess the crop and bring back samples. On his return, the group planned a “pow-wow” attended by the entire village at which they danced all night in a circle dance. During the ceremony, people tested the cones to determine when the harvest should begin; the crop was usually at its prime in early September. If a crop looked poor, the groups might dance for several nights to a full week before beginning the harvest.22

Rabbit drives, also in the fall, afforded ample opportunity for socializing as well as food procurement. The drives were organized by an elected “rabbit boss” who called everyone to a site on one end of a large flat area. The people drove rabbits—both jackrabbits and cottontails—into large nets that were reported to be thirty inches wide and up to three hundred feet long and killed the trapped prey with clubs or arrows. They used all parts of the animals: drying the meat or eating it fresh, cutting the fur into strips and weaving it into blankets, and cracking the bones open to retrieve the nutritious marrow. Plant resources such as grass seeds, roots, and berries were also crucial. Small and large mammals such as marmots, squirrels, deer, and pronghorn were consumed whenever possible. Cooperative driving of rabbits and pronghorn was common to both the Washoe and the Northern Paiute.

After European Americans settled in northern Nevada, the lifeways of the Paiute and Washoe changed dramatically. The newcomers destroyed pinyon forests for mining fuel and took over the most productive lands for agriculture, severely disrupting the lives of the aboriginal hunter-gatherers....