![]()

PART I

ZIONISM AS SETTLER COLONIAL PROJECT

![]()

1

Analysis Matters: Beginning with Settler Colonialism

Sometimes, the very name you give to a phenomenon determines how it is understood and what can be done about it. Since 1948, we have spoken of the “Arab-Israeli Conflict.” This term well describes the six major wars Israel has fought with its Arab neighbors: the 1948 War of Independence, the Sinai Campaign of 1956, the 1967 war, the 1973 war between Israel and Egypt, and the two wars fought in Lebanon (1982, 2006). It may also apply to “informal” wars between Israel and its Muslim neighbors. The “war of attrition” waged between Egypt and Israel from 1967 to 1973 is a case in point. So are the slew of “dirty wars” involving special operations units, targeted assassinations, sabotage, cyber-attacks, terrorism and regime change. Then we have all the diplomatic intrigues and, occasionally, negotiations and “peace processes.” Since 1987, when the first Intifada catapulted Israel’s long-standing occupation into public view, we speak also of an “Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.”

The terms “war” or “conflict” conceal a deeper struggle, however: the colonization of Palestine by the Zionist movement, culminating in a state of Israel ruling over the entirety of the country. To be sure, colonization generates conflict. But “conflict” did not simply erupt for one reason or another. Jews, in fact, had lived in peace with the local Arab population for centuries, if not millennia. They were known in Arabic as yahud awlad ‘arab (Native Arab Jews), al-yahud al-‘arab (Arab Jews), al-yahud al-muwlidun fi Filastin (Palestine-born Jews) or al-yahud al-‘aslin (Native Jews), abna al-balad (Sons of the Land) or, in Hebrew, Bnei Ha’aaretz (Children of the Land).1 Zionism shattered this historic relationship.

Driven by persecution and the rise of nationalism in Europe, it was European Jews with little knowledge of Palestine and its peoples who launched a movement of Jewish “return” to its ancestral homeland, the Land of Israel, after a national absence of 2000 years. In their newly minted nationalist ideology, they were the returning natives. In their eyes, the Arabs of Palestine were mere background. They had no national claims or even cultural identity of their own. Palestine was, as the famous Zionist phrase put it, “a land without a people.” The European Zionists knew the land was peopled, of course. But to them the Arabs did not amount to “a people” in the national sense of the term. They were just a collection of natives – though not the Natives, a status the Jewish claimants reserved for themselves. They played no role in the Zionist story. Having no national existence or claims of their own, the Arabs were to be removed, confined or eliminated so as to make way for the country’s “real” owners.

This form of conquest – for that is what it was – took the form of settler colonialism. Zionists felt a deep sense of historical, religious and national connection to the Land of Israel.2 But in claiming Palestine for themselves alone and rejecting the society they found there, they chose to come as settlers – or more precisely, their choice of settler colonialism rested on formative elements in both Jewish and European societies,3 such as the notion of biblical “chosenness” and a Divinely sanctioned ownership of the Land; a self- and externally enforced ethno-national existence in the European “Diaspora”: embeddedness in the rise of European nationalism, primarily the “tribal” nationalism of Eastern Europe and European experiences of settler colonialism (particularly of Germans in Slavic lands); immediate pressures of economic and religious persecution; and more, which we will discuss presently. The upshot is that Zionists intended to displace the local population, not integrate into it as immigrants would. And displacement is by definition a violent process. Zionist ideology justifying the displacement of the Indigenous population. The “logic” of settler colonialism worked itself through nationalist ideology.4 Early Zionist leaders presented the “conflict” as one ethno-religious nationalism against another so as to deflect attention from settler colonialism, garner the support of the Jewish people and stifle diasporic Jewish opposition. They also used arguments of self-defense to win support of non-Zionist Jews, especially allies in Britain and the US. As the only legitimate national group, the Zionists reduced “the Arabs” into a faceless, dismissible enemy Other. Zionist ideologues like David Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir knowingly altered the framework from one of settler colonialism to that of conflict between an aggressive (and foreign) Arab “Goliath” and the peace-loving (native) Jewish “David.”5

Whatever its justification, the Zionist takeover of Palestine resembled other instances where foreign settlers, armed with a sense of entitlement, conquered a vulnerable country. The European conquest of North America from the Native Americans is perhaps the best-known case of settler colonialism, not to ignore the settlement of Spanish and Portuguese in the Caribbean and parts of Latin America – all of which imported slave labor. The violent settlement of Australia and New Zealand is well known. So is the subjugation by Dutch Afrikaner and British settlers of South Africa, of Kenya and Rhodesia by the British, of Angola and Mozambique by the Portuguese, of Algeria by the French, and of Tibet by the Chinese. Lesser known cases include the Russians in the Kazakh Steppe, Central Asia and Siberia, the Tswana and Khoi-San peoples of southern Africa, the Indonesians in New Guinea, and the Scandinavians among the Sami.6

Now, as we’ve said, settler colonialism generates conflict between the colonist usurpers and the Indigenous population. No population is willingly displaced. But if a conflict involves two or more “sides” fighting over differing interests or agendas, then a colonial struggle is not a “conflict.” Colonialism is unilateral. One powerful actor invades another people’s territory to either exploit it or take it over. There is no symmetry of power or responsibility. The Natives did not choose the fight. They had no bone to pick with the settlers before they arrived. The Indigenous were not organized or equipped for such a struggle, and they had little chance of winning, of pushing the settlers out of their country. The Natives are the victims, not the other “side.” Nor, to be honest, are they a “side” at all in the eyes of their conquerors. At best they are irrelevant, a nuisance on the path of the settler’s seizure of their country, an expendable population, one that must be “eliminated,” if not physically annihilated then at least reduced to marginal presence in which they are unable to conduct a national life and thus threaten the settler enterprise.7 Such a process of unilateral, asymmetrical invasion that provokes resistance on the part of Native peoples threatened with displacement and worse can hardly be called a “conflict.” Rather than the “Israeli/Palestinian/Arab Conflict,” we must speak of Zionist settler colonialism.

Why does this matter? Because it has everything to do with arriving at a just resolution, and you can only do that if you have a rigorous analysis. The conflict paradigm has led us to reduce a century-long process of colonial expansion over all of historic Palestine into a limited struggle to “end the occupation” over only a small portion of it (22 percent). By focusing solely on the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) – the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza – the conflict model leaves Israel “proper” out of the picture altogether. In so doing it legitimizes, or at least ignores, Zionist colonialism over the vast majority (78 percent) of Palestine.

If the problem is a dispute between two countries or a civil war between two nationalisms, as the Palestinian/Israeli “conflict” is often phrased, then a conflict-resolution model might resolve it. But it cannot resolve a colonial situation. That requires an entirely different process of resolution: decolonization, the dismantling of the colonial entity so that a new, inclusive body politic may emerge. This is not to say that the OPT is not occupied according to international law. It is, and after 50-plus years the occupation should be ended. It is only to point out that occupation is a sub-issue. It must be addressed, but only as one element in a much broader decolonization of the settler state of Israel. Only that will end “the conflict,” not limited Palestinian sovereignty over a small piece of their country.

Before moving on to decolonization – or to “resolving the conflict,” as most people say – let us revisit the origins of the Zionist project so that we may understand its basic character. Let’s begin by asking:

WHAT IS SETTLER COLONIALISM, AND HOW CAN IT BE ENDED?

In broad strokes, settler colonialism is a form of colonialism in which foreign settlers arrive in a country with the intent of taking it over. Their “arrival” is actually an invasion. The settlers are not immigrants; they come with the intent of replacing the Native population, not integrating into their society. The invasion may be gradual and not even recognized as such by the Indigenous. And as in the case of Zionism, it is not necessarily violent, at least in its early stages. In the end, a new settler society arises on the ruins of the Indigenous one. A “logic of elimination” which Patrick Wolfe suggests is inherent in all settler colonial projects “disappear” the Indigenous through displacement, marginalization, assimilation or outright genocide.8 Through myths of entitlement, the settlers validate their right to the land. They claim to be the “real” Natives, whether “returning” to their native land or because only they love and will “develop” it. Settler narratives either ignore the Indigenous population or cast them as undeserving, unassimilable, menacing and unwanted. The Indigenous cease challenging the normalcy of the settler society only after they disappear, remaining at best “exotic” specimens of bygone folklore.

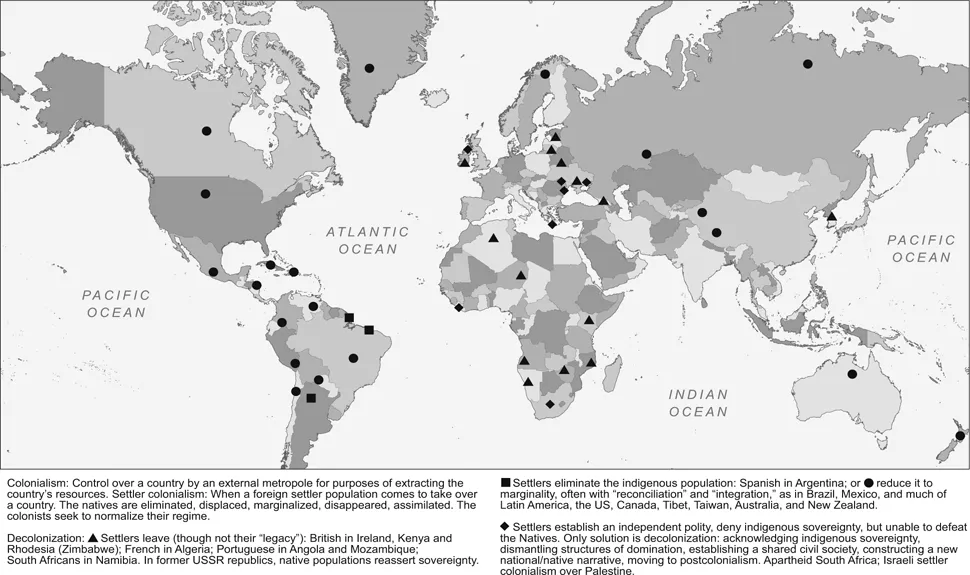

Figure 1.1 Types of Settler Colonialism

Settler colonialism is both an ancient and modern phenomenon. It is also widespread, as the map of settler colonialism in the modern era shows (Figure 1.1).

As we’ve noted, this book is less concerned with settler colonialism per se than it is with decolonization – ending the colonial situation and replacing it with a more equitable system that restores the rights and sovereignty of the Indigenous. But the form that decolonization takes depends upon the forms of the settler regime it seeks to dismantle and supersede, as well as its own history, resources and political situation. The map surveys the major types of settler colonialism and suggests possibilities and forms of decolonization. It is within this theoretical framework that we can locate and analyze Zionist colonialism, Palestinian oppositional agency and the prospects for decolonization.

The Settlers Leave (But Not Their “Legacy”)

Perhaps the most definitive end to a colonial regime occurs when the settlers simply pack up and leave, albeit after prolonged struggle, and hand the country over to its Native inhabitants. This happened in cases of classic extractive colonialism (the British in India, for example, or the French in West Africa or the Dutch in Indonesia), and it happened in a few cases of extensive settlement (French Algeria, for example, Portuguese-controlled Angola and Mozambique; Kenya, Rhodesia and Ireland, all colonized by British settlers; South Africans in Namibia).

Decolonization, however, is a matter of degree; it is a process, not a one-time event. What appeared to be the end of colonialism most often turned into a form of neo-colonization. Either the colonial power continued to dominate its former colony, a condition anti-colonial campaigners derisively called “flag independence,” or the post-colony found itself trapped on the periphery of the capitalist world system, unable to develop and unable to give its formal independence any meaningful political, economic or social content. Mahmood Mamdani,9 who writes of “the institutional legacy of colonial rule” which lasts long after the colonists have departed, notes that the political institutions most likely to collapse after ...