![]()

Introduction

I was born during war. That was in 1939, when Japan was already fighting in China, and shortly before German aggression in Europe would have historians set that year as the beginning of the Second World War. While I was still a young girl, some Vietnamese fought to resist the return of French colonial control, while others supported puppet governments serving foreign rule. With scarcely a pause, I matured as a young woman, mother, singer, and actress, during the period of American civil and military operations in Viet Nam.

War shaped all the circumstances of decision-making for my parents when I was a child. Just a few years later the same was true for me. Moving family from Saigon to a presumed comparatively safe Dalat in 1963, followed by a loveless marriage and then departure from Viet Nam almost ten years later, always fearing for the safety of my own children, is reflective of issues and experiences that tormented millions of Vietnamese people. All that happened during those years shaped my life, even including today, as I revive memories and place them before you.

It is thought by many observers that entertainers are so self-centered and superficial that they must be insensitive to significant events and the sociopolitical tensions around them. This is not true for me. In fact, I believe that fame derived from accomplishment in the arts, sports, or any field of endeavor devolves a special responsibility upon we who are recognized for the excellence of our performance. We should be especially observant, considerate, and at times even comforting of others. Fame adds weight to our every choice of social and even political expression. We can be a positive element within society, and consequently we need to take care.

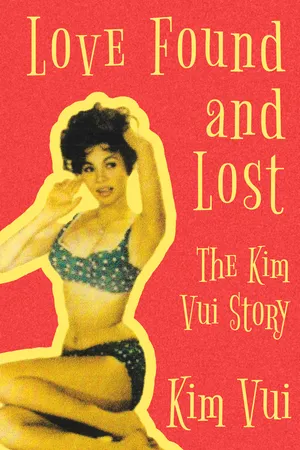

As a popular singer, then actress and sometimes painter, I found performing and creating was always within my Vietnamese national context. I did sing some foreign songs, but most of my music and film roles were not disconnected from the lives of other Vietnamese. Moreover, the popularity derived from my appearance and personality provided an opportunity for me to be informed about contemporary events and to assess ambitions relative to abilities. I was not just an empty-headed pretty face.

A deep regret, looking back, is that although a perceptive observer, I did not participate in political development. I was more concerned for my family’s welfare than anything else, and that is typical for most Vietnamese women because of the expectations placed upon us by our parents. I do not know whether that cultural characteristic will change in the new Viet Nam, or for Vietnamese living in America, but it was certainly authentic and pervasive for my generation.

Memories from Viet Nam are still bound tightly within me even though I now live in the United States of America. I love the country of my birth and worry for Viet Nam. I love equally the country of my new citizenship and care for America’s future. I also understand that for everyone born in Viet Nam and now becoming an American citizen, the transition may be awkward, perhaps even painful. It is tempting to carry old attitudes forward rather than adapt to a new and different environment. Some may think themselves part of an outpost in America from which change can be radiated back to the homeland. We need to ask ourselves whether looking backward is constructive or alternately evasive. Are old attitudes foundational for our children born in a new land? Are we retroactively thinking, or will we be new Americans? We who were Vietnamese and became Vietnamese American can help newcomers make the transition. If there are some among us, not ideal-motivated, who prey upon the confused or linguistically challenged, we must identify and avoid them.

I know everyone in my new country refers to the “Vietnam War” when describing events of 1955–1975, while in Viet Nam that traumatic period is now called the “American War.” I think of those years as encompassing both civil and military operations in Viet Nam and weighty decisions made in Washington. Political action was as important, as calculated and miscalculated, as combat operations; and in fact, the military dimension emerged from an initial civil and political lack of success. Problems between Vietnamese and Americans, and a mutual frustration, were in some part a consequence of national differences.

Be assured, I am not providing another history or account of even one aspect of a particular war; however, a few notes throughout the text may provide a useful sketch of individuals or events mentioned within my personal story. In this context, I want to express my appreciation for consistent encouragement from Tam Minh Kapuscinska, PhD, daughter of Tran Ngoc Chau (who parted from this world in June 2020). I will always remember and be grateful for assistance and support provided by Jerry and Thao Dodson. Travis Snyder and Christie Perlmutter, editors for TTU Press, kept me moving forward and suggested improvements for both accuracy and readability. Jen Weers provided the professional indexing that was beyond my own ability to arrange.

People assume the life of an actress, or any beautiful woman, is an entirely smooth road from one high point of easy living to another. I say instead that life for any woman will always be a challenge. My own is one within which I have been more often sad than happy, and so until now I have always kept my deepest feelings private.

My two special and enduring loves were for my country of birth and for a certain man. Few people knew that the love of my life chose a path diverging from mine. There were brief opportunities to reconcile, but then, and later while still in Viet Nam, we did not reconnect. War sometimes may bring people together, and subsequently the same war can separate them.

I also lost my country. Of course, I don’t mean lost as in the sense of carelessly misplacing car keys, or that Viet Nam in any way disappeared. You can find it on a map. One can travel there. The Vietnamese people survive and endure, as they have in one form or another for two thousand years. But the Viet Nam of my childhood, of my life as a young woman, is no more.

It is from those feelings of loss, from my very personal perspective, that I speak to you now of love found and lost.

Others have written exaggeratedly about me, occasionally to demean, sometimes to flatter; but what follows is my story, in my own words, spoken from my heart, at times with pain, and now shared with friends who will read this book.

Kim Vui

California – Virginia 2021

![]()

Chapter 1:

Escape to Tra Vinh

I was little more than six years old when my family fled chaos in and around Saigon. It was September 1945. French soldiers and police, released from detention, were beginning to reimpose colonial rule in Viet Nam after being set aside by Japan during World War II. Soldiers from Japan had maintained order in the streets, sometimes ruthlessly, after taking complete control from the French earlier that spring; but later in August Japan surrendered to America, and the next month Ho Chi Minh declared Viet Nam independent.

Vietnamese nationalists armed themselves with whatever weapons they could buy or steal and then sought to take control of Saigon while frequently beating or even killing any French wherever they could be found. Cruel acts were justified, many claimed, because those foreigners were representatives of colonial repression. If not, why were they in our country? The Binh Xuyen (a well-known racketeering gang) chose to demonstrate patriotic sentiment by killing foreign and mixed-blood women and children.

British forces arrived, supposedly to disarm the Japanese, but instead ordered Japanese military to restore security by driving nationalists from Saigon. Previously, those same Japanese soldiers were strict but usually correct in behavior. Now Japanese brutality was unrestrained. Just a few houses from where our family lived, a young man was seized by them because he was suspected of having taken wire from fencing around a police post. Everyone in the neighborhood was ordered to assemble and witness the consequences. Father had to bring me because otherwise I would be home alone, not advisable in those days. The young man, barely more than a boy, was forcibly shaved of hair, ear to ear, and then topped with tar before being tied to a chair placed in the sun. His screams and sobs while radiant solar energy cooked his brain were silenced only when his head was chopped off. We knew that, according to our folk belief, he was doomed to wander forever as con ma, a ghost.

French residents, previously detained by Vietnamese nationalists, were now released and rearmed by the British. Regaining control in Saigon, the revived French avenged themselves upon Vietnamese. Anyone could be murdered, anytime, anywhere, all for the cause of restoring order. Not one part of the city was more secure than any other.

Families ran away to rural areas for safety. My father had relatives in the Go Vap area of Gia Dinh Province, but that would have been no refuge. The suburban hamlet was so close to Saigon that there was as much chance for violence there as in downtown city streets. So, my parents decided to make their way, with their daughter, to Mother’s home province, Tra Vinh. We left with other families from the Cho Lon waterfront, all of us on, what seemed to me, an enormous rice barge. Our vessel was one of many moving away from the city. The direction was generally west, toward branches of the great Mekong River, along a trail of canals that in better times brought rice to Saigon for shipment northward within our own country and outward to international markets.

I remember that the canal water was deeply colored from earth eroding along the edges. When shaded by occasional clouds, we floated on a band of dark chocolate brown. But by sunset and with the reflection off the canal surface, we seemed amidst liquid gold. Soft wavelets off our bow were like billows from rolls of fabric tossed in the air and unfurling over market counters. Insects with iridescent wings flew low over the water, sometimes even among the barge passengers. Lightning bugs danced among us just after sunset. I was the only child on board, so I amused myself by capturing a few snails and setting them to slow race on the deck planking. I was oblivious to the danger.

As we drifted through Long An Province, toward My Tho and Ben Tre, this part of our country seemed quiet compared with Saigon. We rode high in the water because, although crowded, the barge was burdened with much less weight than when filled with rice. So long ago was our travel that now I do not remember what powered our train of barges. We proceeded most languidly, barely moving. I recall that sometimes men attached rope to a barge and walked along the canal bank to move us forward. The land around, so quiet, seemed almost abandoned. Occasionally, made possible by our slow movement, those few on shore would call out in greeting and later make farewells by wishing us a safe journey. We travelers simply waved in reply, while drifting away and onward. Our first night’s sleep was on that same barge. Being excited but tired, I do not remember more, no matter how hard I try . . . except that Mother and Father were tense, seeming fearful, despite floating further and further from conflicted Saigon.

Late on the second day we transferred to a smaller, and dirty, old boat, so crammed with other families that the stuttering engine could barely propel the nervous passengers across a broad branch of the Mekong River from My Tho to the Ben Tre landing. We arrived there at nightfall, on a muddy shore by a small clearing made dark and forbidding by the density of the surrounding coconut grove. The following morning, we would all transfer to even smaller boats that could weave through much narrower waterways toward another Mekong branch separating Ben Tre and Tra Vinh Provinces. I was too excited, even though very tired, to sleep easily. Placed between Mother and Father, I could listen to their nervous whispers. I understand now, remembering much that followed, that they feared the unforeseen, the unpredictability, inherent in each stage of our flight south.

My parents did not know that the Mekong Delta provinces were also suffused with violence, not of the street-fighting anti-colonial Saigon city form but no less vicious. Five years earlier, in late 1940, there had been rural revolts in the south, especially severe in scale and duration in My Tho and Ben Tre, the very two provinces we were transiting on our way to Tra Vinh. French military and police, not yet subservient to Japanese command, suppressed the revolts. Their instruments for restoring colonial order, believed legitimate for the purpose of maintaining control over we Vietnamese, included bombing and the massacre of demonstrators. Simmering hatred for the French and any Vietnamese affiliated with them lingered. Now in late 1945 everyone traveling in this region, especially if suspected of sympathy for the restoration of foreign rule, moved at risk to their lives.

The moment small boats poled ashore to a coconut grove, my family (even I) could feel a change of mood among all the travelers, a shift from nervous confidence to diminishing hope and even burgeoning fear. The men who would crew those boats to move us further southward stared malignantly at the Saigon travelers. They spoke roughly while moving around us, even rudely bumping into the passengers while demanding fees for transport to further destination...