eBook - ePub

Donkeys

Anita Gallion

This is a test

Share book

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Donkeys

Anita Gallion

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

There’s never been a better time to add donkeys to a small-scale farm. Friendly, dependable, intelligent, and easy to care for, donkeys are increasingly prized by small-scale farmers. As with tending any livestock, it is always best for the keeper to be prepared. Whether you’re an experienced breeder or a new hobby farmer, this book provides information about the ins-and-outs of buying, caring for, and enjoying these terrific stable companions. Every donkey keeper will gather a bushel of essential information on keeping these remarkable creatures from this colorful new addition to the Hobby Farms series.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Donkeys an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Donkeys by Anita Gallion in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technologie et ingénierie & Élevage d'animaux. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Élevage d'animauxchapter ONE

Donkeys 101

Waaaay back, 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, one line of prehistoric horses began to change. Their ears became longer and thicker; their manes took on a short, stiff, upright appearance; their tails formed a brush at the end; their neighs became brays; and their gestation lengthened from eleven to twelve months. Equus asinus, commonly known as the donkey, emerged.

Understanding the history of the donkey as well as acquiring an overview of donkey types, physical characteristics, social traits, and breeding will provide you with valuable information when you’re ready to select donkeys for your farm.

Donkeys through Time

Donkeys have been part of religion, myth, fable, folklore, literature, and proverb for so long that it feels as if they’ve been with us forever. Their story begins in parts of what is now northern Africa with the progenitor of the modern donkey, the African wild ass (E. africanus). With mitochondrial DNA testing, researchers have recently concluded that modern donkeys are descended from two subspecies of the African wild ass: the Somali wild ass and the Nubian wild ass. Both are currently considered critically endangered, with only a few hundred existing in the wild.

The donkey has never hurried things, and this personality trait has apparently been present from the beginning. Recent DNA studies have reached the conclusion that the domestication of the donkey was a lengthy process. Pinpointing a definite time frame for the domestication has been challenging for researchers because wild asses and their newly domesticated brethren bore a close resemblance. Scientists have had trouble differentiating between the two. During the domestication process, there was an overlap of time during which the donkey was both a hunted prey animal and a beast of burden.

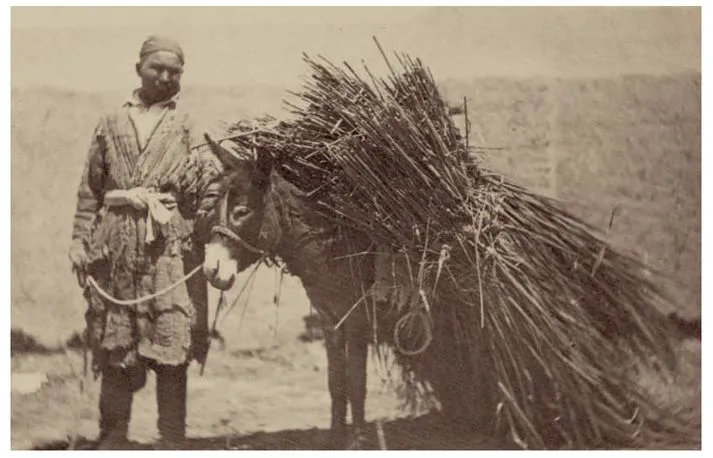

dp n="13" folio="12" ?In late-nineteenth-century Central Asia, a cane vendor transports a huge bundle of sticks by donkey. Donkeys enabled people of Asia and Africa to increase overland trade and still play an important role there today.

Archaeological evidence shows that the nobility of ancient Egypt hunted donkeys for sport, for hides, and for use in traditional medicines. Archaeologists have also discovered articulated donkey skeletons buried in special tombs within the cemeteries of several predynastic and early dynastic Egyptian sites, including Abydos (ca. 3000 BC) and Tarkhan (ca. 2850 BC). A 2008 study on the Abydos skeletons revealed signs of wear and strain on the animals’ vertebral bones, an indication that people of the time used donkeys for riding and for carrying goods.

From the body morphology, scientists have determined that in terms of evolution, the Abydos donkeys lie somewhere between the wild ass and the modern donkey. Based on these findings and others, researchers have concluded that donkey domestication was still an ongoing process around 3000 BC. The burial of donkeys in a high-status area indicates their value to the ancient Egyptians and the possibility that the royal household used these animals.

As the domestication process evolved, donkeys became tremendously important. With the help of friend donkey, people could travel more widely, which led to a large-scale redistribution of food and goods. This period saw a major shift in society, from an agrarian one tied to the land to a more mobile and trade-oriented one. The use of donkeys greatly expanded overland trade in Asia and in Africa. Today, in the arid, rugged regions where donkeys originated, people still use them to carry goods and provide transportation.

Many, many centuries after donkeys began making their way across Asia (and later Europe), they finally set hoof on the soil of North and South America. We have the conquistadors to thank for introducing Equus asinus to the New World. The first asses—four jacks and two jennets—crossed the ocean in 1495 on a Spanish supply ship for Christopher Columbus. Subsequent ships brought horses as well as donkeys; both species eventually spread out across the Americas.

In the late 1700s, George Washington received two large jacks as gifts, both from European races chosen and bred for immense size and bone. These would be the forerunners of new a breed developed in the United States, the American Mammoth Jackstock. Breeders crossed the males of this species with mares to create the mule, a sterile hybrid work animal.

The king of Spain gave Washington the first jack, a large, ungainly, and unattractive Andalusian donkey named Royal Gift. Two jennets of the breed accompanied him. Washington’s friend the Marquis de Lafayette sent the president the second jack, a Maltese dubbed Knight of Malta. This jack, which arrived with two Maltese jennets, was smaller but more vigorous than Royal Gift. Washington crossed an Andalusian jennet with the Maltese jack, a union that produced a large jack named Compound. With this jack, George Washington produced many valuable and much-soughtafter mules. Thus the Father of Our Country unofficially became the Father of the American Jackstock and Mules, as well.

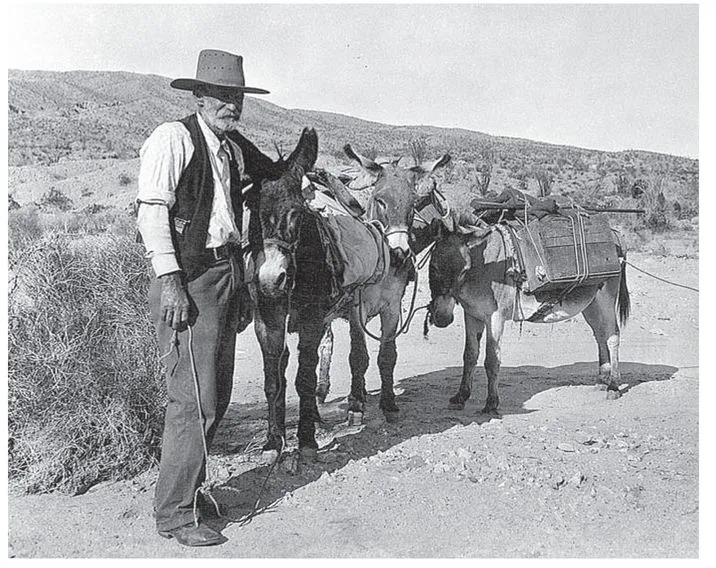

Meanwhile, the small, scruffy descendents of those asses brought over by the conquistadors were making themselves right at home in what would later be the American Southwest. Valued, as they had been for centuries, for their hardiness and ability to survive in arid regions short on green grass and water, the donkeys of the Southwest (known there by the Spanish word burros) became favored by miners during the gold rush years of the mid-1800s. Adaptable and easygoing, donkeys lightened many a prospector’s load, toiling as pack animals, pulling carts, carrying tools and supplies, and for the lucky, hauling gold.

A prospector in the Old West uses a string of three burros to carry tools and other goods through the desert. Its ancestors’ origins in the African desert made the burro (Spanish for “donkey”) the perfect pack animal in the Southwest.

Sadly, then as now, there was no such thing as job security. As mining became industrialized, miners cast the burros out to fend for themselves. They became the ancestors of the feral animals still roaming the region today.

By the early twentieth century, in America and other wealthy nations, the donkey’s role had mostly changed from work animal to pet. In 1929, New York stockbroker Robert Green imported six Miniature jennies and a jack. A foal from these original imports was born on Columbus Day 1929 and, fittingly enough, received the moniker Christopher Columbus. He was the first Miniature donkey born in America.

Today, people use donkeys for riding, driving, guarding livestock against predators, siring mules, breaking calves to lead, and providing milk and meat. There are approximately 44 million donkeys worldwide, with the highest numbers in Mexico China, Ethiopia, and Pakistan, where most still work for a living. In America, the majority of donkeys are kept as pets.

Longear Lingo

Terminology connected to donkeys, mules, and the equine family in general can be confusing. Here’s a little primer to get you started.

Ass: Derivative of the proper name of the species, Equus asinus; commonly referred to as a donkey or a burro

Burro: Spanish word for “donkey,” used mostly to refer to the small feral animals of the southwest United States and Mexico

Gelding: A castrated male equine

Hinny: A (usually) sterile, hybrid equine, created by mating a male horse (stallion) with a female donkey (jennet). Looks similar to a mule and may require DNA testing to positively identify.The hinny is much rarer and more difficult to produce than the mule.

Jack: A male ass/donkey

Jennet/jenny: A female ass/donkey; jenny is slang for jennet

Jenny jack: A Mammoth jack used specifically to breed jennets

John: Slang term for a male mule, sometimes also referred to as a horse mule

Longears: Slang term for members of the ass family

Mammoth donkey (also Mammoth Jackstock): A breed of large ass. Males are 56 inches or taller, and females are 54 inches or taller.

Miniature donkey: Donkeys less than 36 inches in height

Molly: Slang term for female mule, sometimes also referred to as a mare mule

Mule: A (usually) sterile hybrid equine, created by mating a male donkey (jack) with a female horse (mare)

Mule jack: A jack primarily used to breed mares to make mules

Standard donkey: Donkeys from 36 to 54 inches

“What’cha lookin’ at Mom?” Mammoth foal Baby SweetPea pushes up beside her mother to check on going-ons outside the barn. Donkey foals are bright, curious, and anxious to be part of whatever is happening.

Donkeys at a Glance

Domestic donkeys belong to the Equidae family. The genus Equus includes asses, horses, and zebras. Donkeys compose the species Equus asinus. Let’s take a closer look at how donkeys are classified and at some of their physical and breeding traits.

Sizing Them Up

Unlike other species of livestock (cattle, goats, and horses, for instance), the number of actual donkey breeds is fairly limited. Instead, we primarily type and classify longears according to their size. A few distinct breeds do still exist, and we will take a closer look at those breeds in the next chapter. For now we will examine the three main size classifications of donkeys.

Mammoth Donkeys

Although size qualification varies among the official registries, in general jacks and geldings 56 inches and taller are considered Mammoth size, as are jennets 54 inches or taller. Mammoths are the only donkey breed developed in this country.

DID YOU KNOW

Do...