![]()

CHAPTER 1

Integrating Rock Art with Archaeology

Symbolic Culture as Archaeology

ANGUS R. QUINLAN

Rock art is currently enjoying something of a boom in public and archaeological interest, although in North America its study and practice still occur predominantly outside the world of academic and professional archaeology. Only a handful of doctoral dissertations are written each year on the subject. It is largely absent from academic curricula, and only a very small number of professional archaeologists specialize in it. Symptomatic of this professional disinterest and neglect is the large number of amateur archaeologists who make important contributions to the study of rock art, despite lacking formal qualifications in archaeology or anthropology. In some regards this situation mirrors the early history of archaeology as a discipline, when amateurs dominated the field and the subject was entirely absent from university campuses. Yet archaeology’s exclusion from academia was relatively brief compared to that of rock art, for the exclusion of rock art studies from North American academic institutions shows no immediate signs of ending—though there has been sporadic archaeological interest since the days of Garrick Mallery (1893), and Great

Basin rock art attracted the attentions of no lesser a figure than Julian Steward (Steward 1929, 1937). Curiously, a critical retrospective of Julian Steward’s career (Clemmer et al. 1999) mentions his engagement with rock art only in passing, as if it were a kind of hobby, separate from Steward’s anthropological career.

The separation between academic archaeology and the study of rock art has had important consequences for the way in which the field is conceptualized and the state and quality of theory building. Rock art can appear to be highly distinct, its study demanding specialized interpretations and theories that have little purchase in other fields of archaeology. Rock art can be minimally defined as non-utilitarian intentional human-made markings on rock surfaces (Bednarik 2001:31–32), a definition incorporating paintings, engravings, and scratchings, made on boulders, rimrocks, cliff edges, and cave ceilings and walls. Thus, a rock art “site” is essentially a collection or assemblage of images made on natural rock surfaces.

Because of rock art’s landscape context, its imagery has never been treated the same way as imagery placed in constructed structures. Instead, rock art has been treated rather like other non-utilitarian archaeology, as the residue of past ritual practice. Archaeological approaches to ritual are rarely explicit about how ritual spaces are identified. Those that have been explicit about their methodology have used the presence of symbolism to infer a ritual function for the archaeological contexts in which it occurs (Renfrew 1985:24). In such cases the objects identified as functioning as religious symbols (and thus as an index of ritual practice) tend to be non-utilitarian (Quinlan 1993:98). Therefore, since rock art constitutes assemblages of symbolism, it is not surprising that it tends to be naturally associated with the spiritual sphere in archaeological thinking.

Reflecting this tendency, rock art (once its cultural authenticity was accepted) was first theorized as having being used in rituals of hunting magic (Breuil 1952; Heizer and Baumhoff 1959, 1962; Reinach 1903) and more recently as sources of shamanistic powers and records of trance states (Clottes and Lewis-Williams 1998; Lewis-Williams 2002; Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988). Yet these theories are unique to rock art and have rarely been applied to other ritual contexts encountered by archaeologists (though for a recent attempt to extend the shamanistic model to other kinds of ritual archaeology, see Price 2001).

Although the defining property of rock art (imagery made on natural rock surfaces) is unique, in other regards it is not so divorced from other types of archaeology. In particular, the distribution of rock art is not always specialized, and it frequently occurs in association with settlement archaeology, such as lithic scatters, house rings, hunting blinds, and so on, as many of the chapters in this volume illustrate. Whether these other kinds of archaeology are considered an integral part of a rock art site depends to a large extent on the kind of theories we use to bring meaning to the residues of past behavior. For example, researchers working in the Great Basin have drawn rather different conclusions from rock art’s associated archaeology. In the 1960s Heizer and Baumhoff’s (1962) application of hunting magic theory to North America crucially used associated archaeology to demonstrate that rock art sites were present at hunting locales (evidenced by the association of rock art with hunting blinds, animal migratory routes, lithic scatters, and so on). In contrast, Whitley interprets rock art as a means of marking places where shamans made secret pilgrimages to acquire supernatural powers, and thus rock art is rarely associated with other kinds of archaeology (Whitley 1994a, 1994c, 1998c).

In both of these examples, the authors’ interpretations of rock art’s associated archaeology are determined by their preferred theoretical perspectives, which are challenged by the presence of domestic archaeology occurring in association with rock art (see chapters by Cannon and Woody, Pendegraft, Shock, and Cannon and Ricks in this volume). Consequently, the presence of settlement archaeology at rock art sites is downplayed so that the sites’ properties accord with the theoretical expectation. As Cannon and Woody illustrate in chapter 4, this tendency is not confined to rock art specialists; archaeologists are just as likely to ignore rock art at settlement sites.

In both cases, although it is possible to gain some understanding of rock art simply by contemplating its imagery, broader considerations of site context offer more textured accounts of rock art’s cultural meanings. Such an approach recognizes the importance of understanding and establishing context in archaeological interpretation (Hodder 1986:119–20) and the way in which context potentially represents an extension of symbolic meaning (Sperber 1975). Renewed interest in rock art’s fuller context has produced an increase in studies that explore its landscape context as a

source of cultural meaning (Bradley 1997, 2000; Tilley 1991). For example, Quinlan and Woody (2003) have attempted to reconstruct the social roles of Great Basin rock art sites by exploring the implications of their location in or near the routines of domestic life, a theme of several chapters in this volume. Such approaches shift the gaze away from rock art’s imagery and treat it as a light source that can illuminate the social and cultural world of its makers (Sperber 1975:70), also avoiding some of the problems associated with an exclusive focus on recovering the “meaning” of ancient imagery, as illustrated by Maurice Bloch’s cautionary tale of interpreting Zafimaniry (Madagascar) wood carvings: “To the question ‘what are these pictures of’ I was answered with great certainty that they were pictures of nothing. When I asked for a cause or the point of the carvings I triggered the ready-made phrase that there was no point, and when I asked what people were doing I was told ‘carving.’ There was actually one answer that I was given very often . . . that ‘it made the wood beautiful’” (Bloch 1995:213–14).

Understanding Zafimaniry wood carvings is possible only through understanding the significance of the houses and the wood that the carvings decorate. The carvings are not representational but play a part in the process of a house, and the union between the married couple who dwell there, “hardening” or becoming increasingly solid and permanent in structure (Bloch 1995:214–15). In this case symbolism is important for what it actually does, a point made in rock art by the shamanistic approach, which considers some rock art as playing an active role in stimulating trance states (Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1990).

It is rock art’s perceived relationship with past religious practices that partly explains its appeal to the general public and its professional neglect in North American archaeology. Emphasizing distinctive theories of ritual functions has led other archaeologists to believe that rock art has little to offer their fields of expertise and can be safely ignored. Further, archaeology’s will to classification and quantification (which came to the fore in the New Archaeology of the 1960s and 1970s) made rock art a problematic field of archaeological inquiry, as its object of study resists easy classification and is hard to date (Woody 2000a:5–6).

The chapters in this volume reflect the growing confidence of rock art researchers that recent theoretical and methodological developments have

made rock art’s integration into broader archaeological research an achievable goal. Further, rock art researchers justifiably question why North American archaeology has ignored the most visible monument form left by Native Americans, which remains in the place where it was intended to be, in favor of, for example, studying lithic debitage. At last it seems that archaeologists are beginning to take up Julian Steward’s injunction to “set aside their spades long enough to ponder petroglyphs” (1937:406).

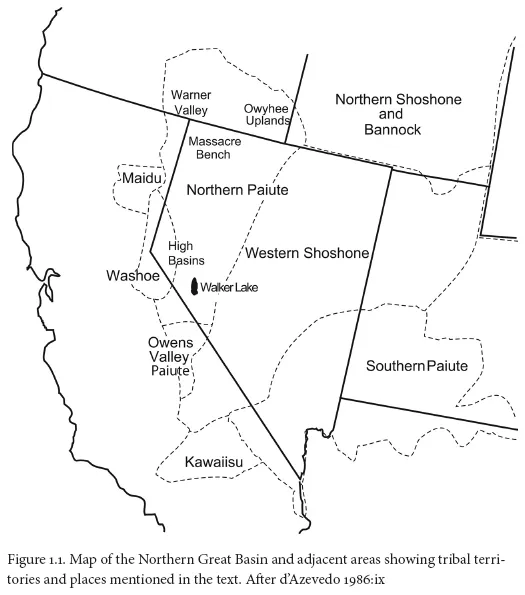

The regional focus of this volume is predominantly the northern Great Basin and adjacent areas (figure 1.1), whose rock art has played an important role in international debates regarding the social and cultural contexts of its original use (Layton 2000b; Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988; Whitley 1992). These debates have tended to focus on ethnography and ethnohistory rather than archaeological studies of the rock art itself. Consequently, the landscape context of Great Basin rock art has been inadequately reported. Several of the contributors whose work is included here (Boreson [chapter 7], Cannon and Ricks [chapter 8], Cannon and Woody [chapter 4], Pendegraft [chapter 5], and Shock [chapter 6]) address this deficit by exploring the relationships among rock art, landscape features, and settlement archaeology in this region, offering an important corrective to the misperception of rock art as a unique landscape monument with a specialized distribution and revealing significant implications for current theoretical debates.

At present rock art interpretation is dominated by approaches that seek to understand its imagery through the framework of ethnohistorical accounts (Francis and Loendorf 2002; Whitley 1992, 1994a, 2000a). Drawing on ethnographic accounts of traditional shamanic practices, such work interprets rock art as having being made and used by shamans in their pursuit and use of supernatural powers (spirit helpers). The argument posits that the art itself portrays specific imagery experienced during trance states. The value of this kind of approach is that it aims to include indigenous theories of being in the effort to understand rock art, assuming that traditional shamanic practices provide an informing context for the interpretation of rock art imagery. The approach is less useful, however, when it is based upon speculative reinterpretations of ethnographic material (for debate on the role of metaphoric reinterpretation of ethnographic data in rock art interpretation, see Hedges 2001; Quinlan 2000a, 2000b, 2001; Whitley 2000a, 2003).

Such theoretically driven works offer specific interpretation of imagery, without necessarily reflecting on the art’s landscape context and its role in adding to site meaning. Cannon and Ricks, Cannon and Woody, Pendegraft, and Shock, on the other hand, explore the interpretive implications of rock art’s landscape context. These authors, drawing on their research from the northern Great Basin, highlight an often ignored property of western U.S. rock art locales: their location in or near the margins of settlement. They document a direct association between rock art and settlement archaeology in their study regions and argue that this challenges the simple assumption of shamanism as the primary informing

context for interpretation. Landscape context discloses the character of rock art’s intended audiences and suggests that the shamanic perspective needs to be complemented by interpretations that consider the domestic routines that took place in the vicinity of rock art (Bradley 2000; Quinlan and Woody 2003). This approach decenters the search for the meanings of motifs as the object of rock art research. Instead, by contextualizing the available informing contexts, these authors challenge popular interpretive theory and situate rock art in the domain of the lived experience of daily life.

Brown and Woody (chapter 2) and Valborg and Cunningham (chapter 3) address the issue of indigenous approaches to rock art, and archaeology more generally, and in differing ways look at the way Native Americans incorporate rock art into contemporary discourses of meaning. Brown and Cunningham are Native Americans, and their views are contrasted with those of their archaeologist coauthors. In the case of Brown and Woody, it is interesting that the indigenous preference is for Western science and Native American viewpoints to be used in a complementary way to support traditional views of the land’s geological history. In the case of Valborg and Cunningham, the tension between archaeological and indigenous frames of understanding is highlighted, opening the question that confronts most researchers today of whether both of these ways of understanding rock art can be accommodated (Echo-Hawk 2000; Mason 2000). Further, Valborg and Cunningham illustrates the symbolic properties of the archaeological record in general—the same body of archaeological data sustains competing theories of being and constructions of cultural identity.

The reasons for rock art’s appeal to the general public and its integration into contemporary material culture is an important issue that is neglected in the literature. When it is discussed (Dowson 1999), public consumption of rock art imagery through its reproduction in popular material culture (mugs, key chains, and so on) and coffee table books is strongly criticized as commodification. However, Quinlan balances this position by examining the role of archaeological research in making such commodification possible by creating a contemporary cultural value for rock art as well as providing the raw materials (photographs, drawings, and so on) used in rock art’s commercial exploitation.

Finally, Boreson (chapter 7) and Ritter, Woody, and Watchman (chapter 9) provide accounts of direct dating studies and fieldwork methodology. They serve as an important reminder that interpretive debate can proceed only so long as archaeologists continue to set aside their spades and record rock art sites. With greater quality of information will come greater resolution in debate, allowing researchers to ask more challenging and appropriate questions of rock art.

![]()

PART I

ETHNOGRAPHIC PERSPECTIVES

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Stories as Old as the Rocks

Rock Art and Myth

MELVIN BROWN AND ALANAH WOODY

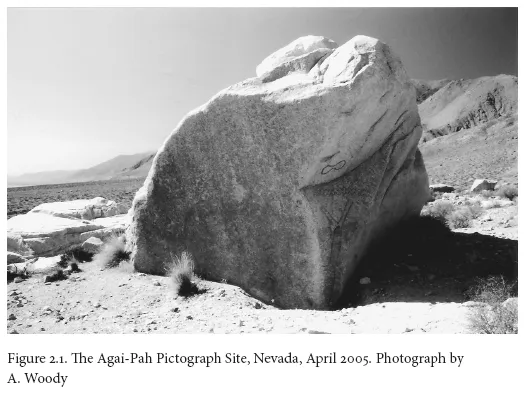

In this chapter we discuss a pictograph site on the west side of Agai-Pah (Trout Lake) or Walker Lake, near the mouth of Copper Canyon on the east side of the Wassuk Range in western Nevada (see figure 1.1). The red iron oxide pictographs are found on the northwest face of an immense boulder (more than 3 meters high and 6 meters long) (figure 2.1). There are several other rock art sites in the general vicinity, but this is the only pictograph site currently known in the area. In the absence of indigenous exegesis, interpretation of rock art imagery can only be speculative. We attempt to contextualize our interpretation, however, by taking into account local oral tradition. Oral tradition has been broadly used in rock art research to offer insights into the meanings of images and theories about the functions of rock art (Lewis-Williams 1981; Vinnicombe 1976). One benefit of using oral tradition to contextualize interpretation is the possibility of capturing some of rock art’s local cultural salience in the present as well as in the past. In the case of the Agai-Pah pictograph site, we relate it to Walker River Paiute (Northern Paiute) traditions of a sea serpent that dwelled in Walker Lake. These oral traditions may represent folk memories of Walker Lake flooding and observations of the fossil remains of ichthyosaurs. In addition, the Agai-Pah site has meaning for Brown as a Walker River Paiute, since he interprets its placement and imagery as referring to flood episodes detailed by geological research.

PREVIOUS REPORTS OF THE AGAI-PAH PICTOGRAPH SITE

The Agai-Pah pictograph site seems to have avoided the academic gaze until the 1920s; it was not noted in Mallery’s (1893) survey of rock art sites and was also omitted from Steward’s seminal study (1929). The first record of the site dates from the 1920s, when it was used as a setting for one of Edward Curtis’s romantic photographs of traditional indigenous cultural practices (1997 [1926]:588). The photograph is of a Native American man with “loin cloth,” moccasins, and paintbrush, supposedly in the process of creating the art. This staged event used the pictograph panel on the western face of the boulder as a backdrop to the portrait of the Native American man. Whether or not Curtis also noticed or photographed the north-facing group of pictographs is unknown. Subsequent observers have concluded that the motifs “appear to be authentic, both stylistically and in their execution” (Tuohy 1983), making it unlikely that they were created by Curtis’s subject.

Subsequently the site was reported in Heizer and Baumhoff’s (1962) gazetteer of rock art sites (figure 2.2), although their drawing of the art is somewhat inaccurate. They commented on the boulder’s dimensions, noted its location, and made a line drawing of part of the north-facet motifs and all of the west-facet ones. In the 1970s it appears that this pictograph panel was implicated in a hoax. Apparently a geologist who resided in the Hawthorne area was sold “Spanish treasure” excavated from the base of the pictograph boulder. The pictographs were supposedly a map to further buried Spanish silver. The “treasure” of Spanish coins, spurs, a bit, and silver bars was in fact base metals and plaster of Paris. Don Tuohy, of the Nevada State Museum, had the unpleasant task of informing the geologist that he had been duped (Tuohy 1983).

PICTOGRAPH CHARACTERISTICS

The red ochre pictographs are located on two sides of a very large granite boulder at the mouth of Copper Canyon; this boulder may have reached its current position as the result of flash flooding. The boulder is about 3 meters high, 6 meters long, and 0.3 meters wide. Perched on top is a smaller boulder (1.82 × 0.9 × 0.6 meters), and to the east is wedged another boulder (4.8 × 3 × 0.6 meters), but neither of these has rock art.

The pictographs are positioned on two facets of the boulder, to the north and west of a vertical ridge. The north-facet motif is very faint and comprises three joined rough triangular shapes with four lines radiating from its so...