![]()

1

The Scales of California Settlement History

New Hope is an optimistic place name, and hope and optimism likely pervaded the thoughts of the approximately 230 Mormons who sailed with Samuel Brannan from New York to California on the ship Brooklyn, arriving in Yerba Buena (San Francisco) July 31, 1846. About twelve families moved on to the Stanislaus River to establish a new community in anticipation that many Mormons would follow them there (J. Davies 1984, 8–10). Despite its name, New Hope Colony did not last very long. The bulk of the Mormons never came to settle in California but instead stopped in the valley of the Great Salt Lake.

By the time the announcement of gold in the Sierra Nevada had become public in 1848, New Hope was gone. Its demise was assured by the colony’s poor location (plagued by mosquitoes and malaria), conflict with Sam Brannan, and the news that the main body of Mormons was not coming to California (Owens 2004, 47–48). In contrast, the Mormons who remained in Yerba Buena found more economic success as the peninsula was poised to grow, due to the event soon to occur in the Sierra foothills to the east (Stellman 1953, 64–65).

The great “new hope” for the future growth of the newly U.S. California began at an obscure place, Sutter’s Mill, that did not fade from the map as New Hope Colony had done. Incidentally, it too had a Mormon presence. John Sutter, needing laborers to build his sawmill on the banks of the American River, hired a number of Mormons (formerly of the Mormon Battalion) who had traveled together to California to fight in the Mexican-American war. They fought no battles, because the war had already ended by the time they arrived in San Diego on January 29, 1847 (J. Davies 1984, 6). Many of these Mormons decided to stay in California for a time to work, and at least five hired on at Sutter’s Mill. They were on the job when James Marshall discovered gold in the tailrace at the mill site in January of 1848, and two of them recorded some of the earliest accounts of the discovery in their personal writings.

Regardless, instead of a new hope emanating from an agricultural colony in the San Joaquin valley, it sounded with a thunderous clap from the small sawmill at Coloma, recorded and expanded along the river by Mormon laborers. In San Francisco, Samuel Brannan promoted and advertised the discovery with verve, for he stood ready to make his transitory millions through the newspaper business and by selling supplies to the miners who soon would come. Brannan’s mercurial rise and fall is one of the great stories of early California history.

But for every Sutter, Marshall, and Brannan, there were thousands of relatively unknown characters who also made their mark on the promising California landscape. Most of their movements are lost to history, but dependence and interaction between the mines in the Sierra Nevada foothills and the San Francisco Bay area were ongoing and significant. One Mary Ann Fisher Cheney, a Mormon immigrant who arrived on the Brooklyn, wrote in 1850 of how she and her husband panned for gold in the Sierra and raised produce on their farm at San Jose. She noted that over the winter of 1849–1850, they were able to sell a dozen eggs for the incredibly high price of $6. These exorbitant prices did not last long, as farming was suddenly a very attractive option for the forty-niners and other immigrants (Owens 2004, 253–54). Mary Cheney and her husband are just two examples of the thousands of people who arrived to the valleys blossom with produce and livestock, to provoke the rivers and streams to give forth their riches, or both. Thus, the symbiotic cycle between the mountains and valleys of California was established. More importantly, it was often the lot of successful or discouraged miners alike to be integrally connected with the economic development and spatial dependency that ensued because of the monetary courses they took.

PEOPLING OF CALIFORNIA ACROSS TIME AND SPACE

This region of California certainly has a story to tell. The story is hidden beneath a wave of untold numbers of gold miners, merchants, farmers, politicians, carpenters, and ever more people from various backgrounds and corners of the world. Amidst this mass of historical data is an intricately woven tapestry of interrelated people and events that literally created this dynamic state. At its most basic level, northern California can be geohistorically dissected into composite elements of individual persons acting in their defined portions of the landscape at a particular point of time. Very quickly, study at this individual level requires an agglomeration of individuals, first in family units, next in small communities or neighborhoods, followed by counties or cities, and finally a regional system. Just as in the human body, where no one atom or cell can act individually without affecting its surrounding elements, the history of nations has been written and shaped both by the most incongruous farmer and the exceptionally boisterous politician.

This book explores the lives of the many people who made the valleys of California bloom within a wide variety of human landscapes. Dozens of excellent books have been written concerning the early growth and development of the state, from sweeping comprehensive histories (Bean and Rawls 1983; Brands 2002; Lavender 1972; Roske 1968; Starr 1973) to regionalized and geographically focused monographs (Brechin 1999; Fradkin 1995; Hardwick and Holtgrieve 1996; Holliday 1999; Lotchin 1974). This book adds a particular perspective to that large and competent body of literature. It illustrates how the new settlers’ initial land-altering presence persisted over time through their family relationships, and how the early pioneers and miners periodically transformed themselves in response to constantly shifting economic paradigms. By multiplying these individualistic experiences across the far-flung reaches of the California system into larger and larger scales, this book uncovers the secrets that propelled a sleepy post–Mexican outpost into a flurry of restless, youthful growth, which has continued virtually unchecked until today.

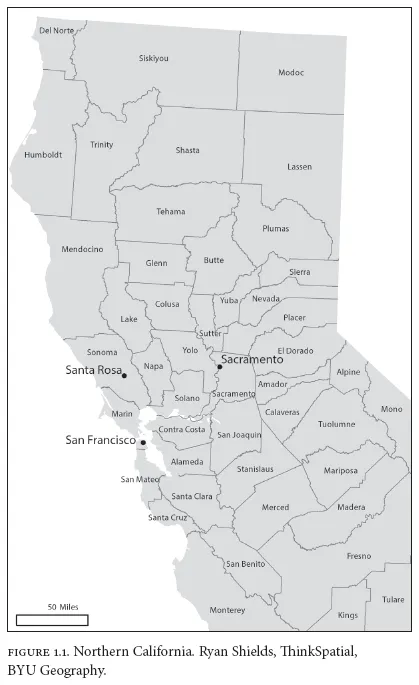

As the unending throng of people pushed into California beginning in late 1848 and early 1849 and throngs surging into the next several years, they changed the region forever. Their impact on the rivers and forested slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountain foothills was significant, but most of the players in this drama were like the butterflies that cover the hillsides in the fairer months but disappear in the winter. The miners were constantly on the lookout for better diggings in other sparkling streams in other valleys, and so permanence of address was not common. This seething, never-resting mass of opportunistic argonauts often made its most lasting impacts in the cities and farms of other parts of the state after individual luck ran out, or when people became tired of the uncomfortable life of a miner. San Francisco and Sacramento would likely have not grown so spectacularly were it not for the immigrants and the businesses associated with mining. In this way, all of northern California was intertwined and interrelated in the nearly living regional organism that matured into an economically innovative and increasingly dynamic spatial system (fig. 1.1).

It is hard to fathom the movement of thousands of people across the face of America in search of “easy” riches. Money has the ability to motivate people, where other incentives do not. Try to imagine the sheer magnitude of the multitudes of men and women who streamed across the continent on foot or horse. Throngs crowded onto ships and sailed around South America or tempted the sting of death by malaria or yellow fever in crossing the Central American isthmus. Some ethereal elation awakened an innate optimism that spread around the world. The gravitational pull of California was too much for people of many walks of life to try and counteract with sensible talk and quiet contemplation. It was a now-or-never moment, so off they went, following the siren song of the waters rushing off the slopes of the Sierra Nevada. Yes, many did strike it rich, but it usually came at the price of a tremendous amount of backbreaking work, long separation from loved ones, and the threat of life-shortening accidents and illnesses. Additionally, there were countless numbers who could barely hold still long enough to be counted by the 1850 U.S. census. They moved so quickly that there were very few of the same people in the same counties only a few years later.

One wonders whether a state founded on the principles of individual enterprise and profit could survive the eventual depletion of the “easy” placer mining locales, as corporate mining became the norm. This transition, from the very short-lived raucous gold rush to a more orderly development paradigm, is not often evaluated as the fluid process that it was within the various spatial scales in which it occurred.

The powerfully deceptive lure of riches for all who could find them is the simple explanation as to why so many people left their homelands and traveled thousands of miles to an unfamiliar land. Yet, there is something deeper, more elusive woven into the fabric of this and all stories of real lives. It is the longing for opportunities and places that are better in some way from one’s present home and means of livelihood. Were the immigrants to California more opportunistic, more dissatisfied, or more desperate than those who stayed home? Without the ability to interview a large swath of these miners, it is impossible to tell how their thought processes differed from those they left behind. However, some ideas are revealed through reviewing the actions of the first California pioneers. This book follows the early Californians as they created their new society, and it examines whether they were successful in constructing a lasting landscape of prosperity and happiness.

PEOPLE’S PRODUCTION OF LANDSCAPE THROUGH TIME

There are four dimensions that intersect migration themes in the unfolding history of any place. First is the geography (landscape). The land is the base that people live on and use to make their livelihood. Although human and natural forces modify it, it retains a tremendous degree of continuity over time.

Second is the dimension of history or time. Discrete events can be contextualized within the larger framework of connected multiple events during the general period, which helps to explain their occurrence, ties them into the larger cycles of history, and underscores forward and backward links that reach far beyond the issue in question.

Third is the dimension of people, specifically, families. People are the actors upon the landscape, and individuals are tied together in time and space by their family relationships. Migration and marriage patterns, for example, are influenced predominantly by the historical period and familial factors (Macpherson 1984). Family genealogies are thus firmly entwined within both the temporal or historical dimension and the geographic or spatial dimension. In essence, the unveiling of a family history that spans numerous generations reaches out across space and time to reveal the greater historical trends of the world, as well as incorporating the friction of distance (or the inertia that often accompanies one’s life-migration history) and the tendency of family members to cluster more closely over time compared with the general population (Bieder 1973).

Fourth and finally, is scale. Migration at the local level affects neighborhoods and other small locales. As scales shift upward to the community, scores of people moving in and out shape the destiny of the place. Ultimately, large regional structures evolve over time according to a complicated aggregate migration network of paths (transport routes) that move large numbers of people back and forth across a landscape of uneven, yet changing opportunities. Writers have produced a tremendous number of excellent works regarding this era and place in American history, but the rapid development of northern California has not often been approached from the multiscalar perspective that is introduced and explained in this book.

A MODEL OF MIGRATION AND SETTLEMENT

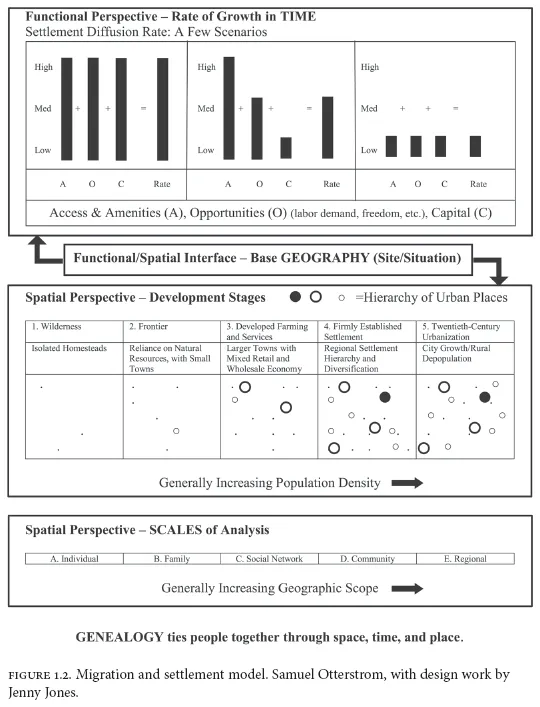

Combining the four dimensions of geography (landscape), time, genealogy (families), and scale produces a wide range of potential perspectives from which to make inquiry into the rapid settling of northern California. Each chapter of this book, although different from the other in terms of its migration dimension, is a piece of a related whole. To show these interconnections, I introduce a migration and settlement model derived from the specific historical geography of this region that could be applied to other places around the country. The model recognizes that the migration and settling process has had many similarities across different regions, but the rates and spatial manifestations have varied according to distinct geographic, economic, and temporal characteristics (fig. 1.2). It is loosely based on the concepts and models of others including Brown (1981), Meyer (1980), Muller (1977), North (1955), and R. Walker (2001a), as well as Bowden et al. (1971) and Turner (1953). California’s developmental growth was rapid. Other regions of the country doubtless proceeded through the same general settlement process at quite different speeds. It is hoped that this model and approach may be useful to others studying historical settlement geographies in the United States.

The model combines the four dimensions to organize the analysis of migration and settlement change in various places. The functional perspective equates with the time dimension, meaning that migration is either rapid or slow through time depending on various factors. The spatial perspective focuses on settlement stages and the scales of analysis, which depend on the size of the migration and settling processes being studied. The geography (landscape) dimension is the interface between the two perspectives. Lastly, the genealogy dimension ties people together through space, time, and place, by blood and association.

Functionally in time, migration rates depend on the push and pull factors extant in both source origins and the migration destination. These factors include economic opportunity, amenities, access (transportation elements), social structure, freedom, and capital in the hands of migrants. Positive migration rates lead to settlement development, and regional expansion. Negative rates point to settlement stagnation and, in some cases, ghost towns, of which California has a large share.

The interface between the functional and spatial perspective is the geographic site and situation of the region, or base geography. The imprint of humans on the landscape, be it fast or slow, always occurs within the context of the extant geography. The outward reach, or diffusion of people and settlements is at first more reliant on natural resource availability, such as arable land, harvestable forests, productive fisheries, and mineral resources. Over time, the human occupance of the land changes, as manufacturing, services, and transport sectors grow on the original landscape and as greater population densities in core cities and towns occur.

Migration pathways facilitate or impede the speed and timing of the settlement of an area. These access routes are part of the geographic interface, and they greatly affect the rates of growth illustrated by the functional perspective. Initially, exploration followed by migration opens an area to future settlement. All places that have inhabitants must have some kind of access. The trails, roads, sea routes, and railroads that connected California to the outside world were the conduit for trade and for enhanced population growth. These pathways are still essential for the livelihood of the region, and their geographic placement and utility can channel growth to certain locales while handicapping it in others.

In the spatial perspective portion of the model, natural population growth and migration spur the development of settlements over a number of different stages that range from the individual farmstead to the complicated regional city-system. This progression through settlement development stages can be considered within five spatial scales. The first is the personal or individual scale that considers how seemingly unrelated people move and interact. Second is the family scale, which closely follows the individual scale. Migration and settlement patterns are greatly affected by extant and developing family relations. Third is the social network scale that creates cohesive groups of people due to religion, language, or other cultural characteristics. Whereas social networks may be dispersed or concentrated within the geographies of other culture groups, the fourth migration scale of community is placed within the specific confines of a bounded populated place. It results as individuals, families, and social organizations congregate and build economically diverse towns and cities. Finally, at the fifth migration scale is the development of regional economic and political relationships among many towns and villages in a specific area.

How do all of these pieces fit together? The genealogy perspective makes this more understandable. Its premise is that people at all scales, related both by family ties and social connection, are highly connected to their genealogical relationships in the way that they make their living and whether they migrate or stay in an area over time. Thus, the narrative explores the relationships of the individual to the community and to the region, always illustrating how the migration of related people across space and their economic interactions among various places serve as binding agents in regional place making. The movement of people across the land over time has resulted in marks they have put upon it through building, farming, and transporting. These marks, made in an endless attempt to live and improve living, are considered here within the various spatial scales of the varied geography of northern California during the last half of the eighteenth century.

SCALE, GEOGRAPHY, AND TIME IN CALIFORNIA’S PAST

I start at the most basic levels of geography, which are the individual to family scales, where migration tends to move toward preconceived “greener pastures” or a “promised land.” It is a manifestation of the human desire for greater opportunity and locational improvement by migrating to a new place—be it a hoped-for Eden or Utopia—that will decrease personal poverty and heighten happiness. In other words, people use migration—often coupled with career shifts—in seeking to quench the burning desire for a better life. Alternatively, satisfaction with one’s position in life, both socioeconomically and geographically, leads to a decrease in personal and family migration. Examining the lives of early Californians reveals the extremes of restless gold miner movement in the 1850s and 1860s followed by a more orderly migration flow in subsequent decades. The sheer volatility of gold mining communities in demographic structure and population persistence is a sure indicator that the argonauts had not found what they were looking for. Eventually, many of these miners settled down and turned to farming and other more traditional occupations as well as resuming a normal family life, often in other parts of California. Although the mines were the initial attraction and motivator, life as a “former miner” appeared to be more satisfying than continued toil and sweat in the mining districts.

Although frontiers were first mostly filled with men seeking their fortune, it was not long before women and children followed in corresponding numbers (Boeckel and Otterstrom 2009). These family pioneer migrants sought out a variety of opportunities in the West: farmers came because of low-priced or fertile farmland (hopefully both); would-be miners came because of fervent dreams of wealth; Mormons came to and left California because of religious ties and obligation. Otherwise, there was a great propensity for people to stay close to family homelands, especially during this late 1800s period. This was certainly the case in California. As more families moved to the Golden State, including fathers and husbands who had left brides and children to seek fortune and then returned to the East or other places to retrieve them, migration patterns also changed. Flows were ...