- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Class Acts explores the development of lifestyle marketing from the 1960s to the 1990s. During this time, young men began manipulating their identities by taking on the mannerisms, culture, and fashion of the working class and poor. These style choices had contradictory meanings. At once they were acts of rebellion by middleclass young men against their social stratum and its rules of masculinity and also examples of the privilege that allowed them to try on different identities for amusement or as a rite of passage. Starting in the 1960s, advertisers and marketers, looking for new ways to appeal to young people, seized on the idea of identity as a choice, creating the field of lifestyle marketing.

Mary Rizzo traces the development of the concept of lifestyle marketing, showing how marketers disconnected class identity from material reality, focusing instead on a person's attitudes, opinions, and behaviors. The book includes discussions of the rebel of the 1950s, the hippie of the 1960s, the white suburban hip-hop fan of the 1980s, and the poverty chic of the 1990s. Class Acts illuminates how the concept of "lifestyle," particularly as expressed through fashion, has disconnected social class from its material reality and diffused social critique into the opportunity to simply buy another identity. The book will appeal to scholars and other readers who are interested in American cultural history, youth culture, fashion, and style.

Mary Rizzo traces the development of the concept of lifestyle marketing, showing how marketers disconnected class identity from material reality, focusing instead on a person's attitudes, opinions, and behaviors. The book includes discussions of the rebel of the 1950s, the hippie of the 1960s, the white suburban hip-hop fan of the 1980s, and the poverty chic of the 1990s. Class Acts illuminates how the concept of "lifestyle," particularly as expressed through fashion, has disconnected social class from its material reality and diffused social critique into the opportunity to simply buy another identity. The book will appeal to scholars and other readers who are interested in American cultural history, youth culture, fashion, and style.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Class Acts by Mary Rizzo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Rebel’s Swagger

The White Working-Class Rebel as Proto-Lifestyle

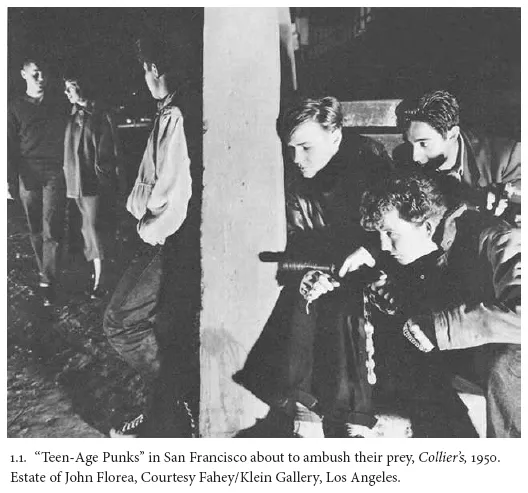

The photo that accompanied the 1950 article “Teen-Age Punks” (1.1) would have been instantly legible to the readers of Collier’s magazine as a depiction of youth gang activity.1 Juvenile delinquency had been a major topic for social scientists, government leaders, and journalists even during World War II: 1,200 articles about the issue were published in the first half of 1943 alone.2 Since the war, the problem had only grown. Newspapers and magazines pathologized youthful delinquents, as in the Collier’s article, which described them as subhuman: “young wolf packs roam[ing] the streets for prey.” The intended victims—the photo’s clean-cut couple—are a model of heterosexual romance and are unaware of the violence that awaits them. But a second glance reveals anomalies. Clearly, the photo is staged, as it shows the gang members moments before ambushing the couple who is being lured by their lookout. Indeed, the caption identifies the gang members and victims as students in the “suburban Precita Valley Boys’ Club . . . helping to fight against ‘punkism’ ” by demonstrating the methods used by these “punks.”3 In order to teach other young people to avoid crime, these young middle-class men borrow the clothes, dress, hair, and comportment of juvenile delinquents. To succeed in their educational goal, they must accurately embody the delinquent. In this way, the photo eerily portrays the deepest fears of middle-class parents in this era: that there was little except clothes and style that separated their children from delinquents.

The photo also draws a distinction between the vulnerable middle-class couple and the dangerous youth gang. As historian Elaine Tyler May has described, in the postwar period “the powerful political consensus that supported cold war policies abroad and anticommunism at home fueled conformity to the suburban family ideal. In turn, the domestic ideology encouraged private solutions to social problems and further weakened the potential for challenges to the cold war consensus.”4 Such domesticity required a particular kind of masculinity, focused on home and family, which was validated through government policies and popular culture. The delinquent male, however, remained on the outside. Discourse, like the Collier’s article, described the young male delinquent living a life on the streets, in the company of other young men (rather than in a feminized domestic sphere), and looking for kicks. The middle-class husband and father and the delinquent were mutually constitutive, given meaning only through comparison with each other. While schools and other youth institutions tried to guide young men to the first path, some, including young men from middle-class families, chose the other one. Through acts that ranged from skipping school to vandalism to wearing blue jeans, these young men performed an identity opposed to that proscribed by television sitcoms and suburban developers.5

Cultural producers, like filmmakers and marketers, understood the appeal of the juvenile delinquent to young men, but had to tread carefully in Cold War America. There could be no juvenile delinquent starter kit, complete with tight T-shirt and pomade. In an era when marketing theory shifted from mass marketing based on demographics to more nuanced understandings of consumers through psychological profiles, the concept of lifestyle as a connected series of attitudes, values, and commodities freely chosen by consumers had not yet come to the place of importance it would assume a decade later.6 Young men interested in adopting this identity, or aspects of it, had to learn from other young men and from popular culture, especially films marketed to youths that reveled in sensationalized portrayals of delinquents under the cover of social reform. Through the narratives and marketing of two of the most important films of the mid-century, The Wild One (1953) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Hollywood created a proto-lifestyle of the delinquent as a white working-class male rebel, and taught teens how to embody him. Both films have been analyzed as documents about American masculinity, family relations, and delinquency, but here they will be examined in terms of their presentation of class identity in the creation of the white working-class male rebel as represented by two of the quintessential rebel males of the period: Marlon Brando and James Dean.7 Although national rhetoric asserted American classlessness, the working class did not disappear inside the burgeoning middle. Instead, it existed in this imaginary space in popular culture, and within other discourses about gender, race, and, especially, juvenile delinquency. In creating the white working-class male rebel as a proto-lifestyle, filmmakers and marketers set the template for the use of working-class masculinity to fulfill the needs of the middle class for the remainder of the century.

CONTAINMENT, REBEL STYLE

When Pete Seeger famously sang in 1962 that suburbia was made up of identical “Little Boxes,” lived in by identical people, he voiced a common critique of the postwar period: the growth of the middle class had resulted in a vast conformity that eradicated individuality. Not everyone bemoaned this state. While the song did not indicate what made everyone the same, a 1959 report from the Department of Labor made clear that class mobility had caused this conformity: “Today the wage earner’s way of life is well-nigh indistinguishable from that of his salaried co-citizens. Their homes, their cars, their baby sitters, the style of the clothes their wives and children wear, the food they eat, the bank or lending institution where they establish credit, their days off, the education of their children, their church—all of these are alike and are becoming more nearly identical.”8 While such benefits were not actually equally accessible to all, the report suggests that due to the great postwar economic boom, the “wage earner,” or working-class man, merged with “his salaried co-citizens” to become part of a huge middle class that proved American consumer superiority. While in the past “way of life” (note that the report does not yet use the term lifestyle) separated the classes, in postwar America everyone’s access to the same goods fundamentally indicated the elimination of class differences, at least for whites.9 This report is indicative of much postwar discourse that, as cultural historian Alan Nadel has argued, supported “the pervasive image of a normative American: white, heterosexual, upwardly mobile but always middle class (regardless of income or occupation), generically religious, and uncommonly full of ‘common sense.’ ”10

Although the Department of Labor report and “Little Boxes” approach middle-class identity from opposite ends of the ideological spectrum, they both miss something essential. In the context of the outward sameness that they identify, small distinctions became proportionately more meaningful as a way for individuals to express themselves. Specifically, these distinctions became the cultural markers of class identity. Sociologist William Whyte acknowledged as much in his discussion of the suburbs in his influential book The Organization Man: “There is much more diversity in the scene than the bystander sees, for the more accustomed one becomes to the homogeneity, the more sensitized is he to the small differences.” As Whyte saw it, middle-class suburbs dampened conspicuous consumption since everyone wanted to be alike. Outside them, however, a different situation existed. He used cars as an example: “Of the thousands that lie in the parking bays, few are more expensive than the Buick Special, and rakish touches are not too frequent. Only in near-by industrial towns do people show exuberance in the captainship of the American car; foxtails and triumphant pennants, like Cyrano’s plume, fly defiantly on cars there, and occasionally from the radiator a devil thumbs his nose at the passing mob. Not at Park Forest; whatever else it has, it has no panache.”11 The middle class eschewed “rakish touches,” and thus lost any “panache.” Instead, style is located in the working classes living in the “near-by industrial towns,” who relished their “foxtails and triumphant pennants” as a means of distinguishing themselves from the middle class, as suggested by the devil who “thumbs his nose.” While the Department of Labor saw the classes becoming more alike through consumption, Whyte showed that class distinction still existed and that consumer consumption defined it. To be middle class meant not buying a car with “rakish touches” since that would signal the persistence of working-class consumer practices, which had to be expelled in the move to the suburbs.

As this suggests, the containment culture of the postwar period was defined through exclusion—of nonwhites, gays and lesbians, and the working class. The sitcom suburbs ensured their whiteness through discriminatory lending practices against both nonwhites and women.12 The ferocity with which the government persecuted gay men and women during the Lavender Scare of the 1950s and 1960s demonstrated how the boundaries of middle-class identity were policed in terms of sexuality.13 Even designers of household goods tried to convince working-class families who had just begun earning middle-class salaries into giving up their flashy furniture for more tasteful décor. However, working-class women who suddenly had access to middle-class pocketbooks used their power as consumers to make designers cater to their tastes, by adding “bulk and size” and “embellishment and visual flash” to household appliances, a rare example of the working class triumphing over the replication of middle-class taste.14

Equally important in defining containment culture was the rigid construction of middle-class masculinity. As the domestic sphere grew in importance, much attention was paid to questions of what would happen to men as they focused on home and family, as they were expected to do. Mass popular culture, especially television sitcoms, offered the dominant vision of the middle-class husband and father and guided men on how to perform this identity. With gentle comedy that often poked fun at men adjusting to middle-class domestic life, television shows like Leave it to Beaver were part of a national project to educate men about a new kind of masculinity.15

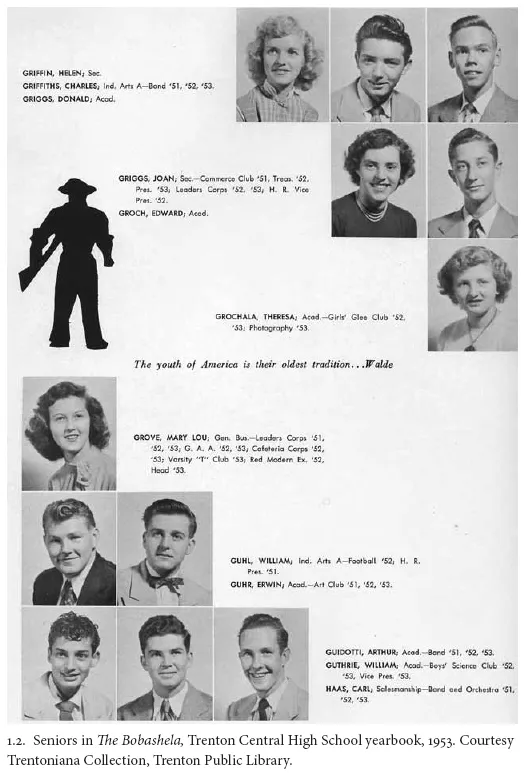

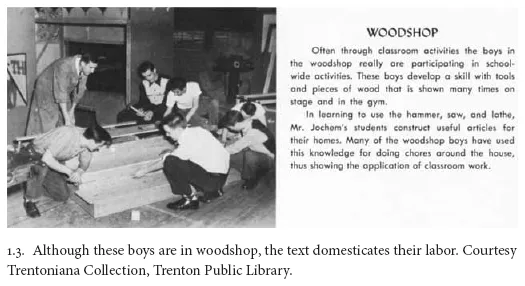

Young white men also learned these identities beginning in school. As the secondary school population grew (more than 80 percent in New Jersey between 1952 and 1962), comprehensive high schools drew large numbers of students together and taught them how to be proper adults.16 Trenton Central High School in Trenton, New Jersey, was, in many ways, a typical example. A page from its 1953 yearbook, with a sea of seniors dressed in suits and ties gazing out of frame as if in anticipation of the bright future awaiting them, shows how young men were expected to fit into middle-class roles (1.2). Even photos of students engaged in manual labor were reinterpreted in terms of middle-class masculinity (1.3). Instead of suits, the young men wear T-shirts, button-down shirts of contrasting colors, and rolled-up blue jeans as they work in the woodshop. Rather than emphasize the vocational applicability of these skills for working-class students and others, the caption domesticates it, noting that the students’ main accomplishment is to “construct useful articles for their homes.”17

Just as often, though, American culture showed men struggling with this role, which seemed to require the loss of the autonomy and freedom that had defined manhood.18 As protagonist Tom Rath bemoans in the novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, the exemplary expression of middle-class male angst in this period, suburban and corporate culture demanded conformity, other-directedness, steadiness, and a deep commitment to home and family. As Rath describes himself, “I’m just a man in a gray flannel suit. I must keep my suit neatly pressed like anyone else, for I am a very respectable young man. . . . I will go to my new job, and I will be cheerful, and I will be industrious, and I will be matter-of-fact. I will keep my gray flannel suit spotless.”19 The gray flannel suit with its dull color, baggy shape, and overwhelming sameness is endlessly replicated by the white-collar workers who parade through Grand Central Station on their way to meaningless jobs that rely on personality traits like a sense of humor and a matter-of-fact attitude more than on traditionally manly virtues like frankness and authority. The “spotless” suit becomes the means of performing a self at home in the increasingly corporate world of postwar America.

While the middle-class husband and father predominated in popular culture, other masculine identities existed as alternatives, from the intellectual beatnik to the bachelor playboy (as Barbara Ehrenreich has written of Playboy’s founder Hugh Hefner, he “later characterized himself as a pioneer rebel against the gray miasma of conformity that gripped other men”).20 Given meaning in relation to each other, these identities suggested that there were competing narratives of masculinity in this period. The juvenile delinquent, or the white working-class male rebel, became one of the most discussed of these possible identities. Like the others, the white working-class male rebel was defined in opposition to the middle-class man who was weighted down with responsibility and contained within the domestic sphere. Even famed criminologist Albert Cohen suggested the allure of the rebel: “The delinquent is the rogue male. His conduct may be viewed . . . as the exploitation of modes of behavior which are traditionally symbolic of untrammeled masculinity, which are renounced by middle-class culture because incompatible with its ends.”21 The white working-class male rebel was both a figure to be desired by middle-class men missing “untrammeled masculinity” and a scourge to be eradicated by authorities like schools and the police. Rather than juvenile delinquency being seen as a reaction to the middle-class masculinity of the Cold War, it was seen as being caused by mass culture, dysfunctional families, and a lack of institutions for youths.

As the working class was absorbed into the middle-class suburbs or expelled from them, the rebel figure came to haunt its margins, especially as middle-class youths began to adopt his style and behaviors. As Dr. Harris Peck of the New York City Court of Domestic Relationships argued at a conference in Trenton, New Jersey in 1956, “delinquency, which appeared to be a phenomena [sic] largely manifested in lower socio-economic levels in great urban areas, appears to be on the move into the middle classes and into the suburban and rural areas.”22 In New Jersey, for example, stories of privileged youths robbing neighbors and businesses, possessing guns, and, in the most extreme, murdering other youths and adults, spurred public outcry. Reports showed the statistical shift of delinquency from urban areas in the 1930s to suburban and rural areas by mid-century.23 While delinquency among the working class was normalized, middle-class delinquency boggled the public mind. New Jersey’s reaction was typical. A state senate commission invited church leaders, school superintendents, police chiefs, and social workers to numerous public hearings in the mid-1950s to try to address this scourge, producing volu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction: The Paradox of Class

- 1 - The Rebel’s Swagger: The White Working-Class Rebel as Proto-Lifestyle

- 2 - Rejecting Modest Comfort: Voluntary Poverty and Men’s Countercultural Style

- 3 - The Essence of Social Class: Marketing Lifestyle

- 4 - The Countercultural Peephole: Selling Counterculture as Lifestyle in Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical

- 5 - Class, Remixed: Hip-Hop Fashion and Black Masculinity as Lifestyle

- 6 - Necessary Objects: Alienation as Lifestyle in Poverty Chic

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Index