![]()

CHAPTER 1

Transportation in the Bay Area Before the Bay Bridge

Historians generally agree that the Bay Bridge revolutionized transportation in the Bay Area and throughout Northern California, without specifying the transportation modes it affected. This chapter attempts to measure that impact with reference to the three principal means of travel impacted by construction of this bridge: navigation, mass transit, and vehicular traffic.

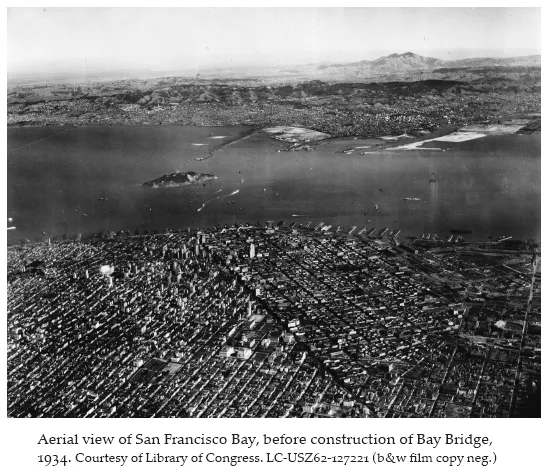

Like most great urban areas in the United States, the San Francisco Bay Area was settled first by sea; it was only later linked to the rest of California and the nation through ground transportation modes. Historian Kevin Starr observed, “No American city is more fortunately, or more unfortunately, sited than San Francisco, surrounded by water on three sides. San Francisco stands in splendid isolation, a virtual island off the coast.”1 The East Bay and Peninsula cities were also settled initially via sea but were more quickly provided with effective ground transportation than was San Francisco. Among its many contributions to the settlement history of the Bay Area, the Bay Bridge for the first time provided San Francisco with a direct ground link to the East Bay and thus to the rest of America.

Navigation in the Bay Area before the Bay Bridge

Navigation in the Bay Area before the building of the Bay Bridge can be seen as comprising two basic modes: cargo-carrying ships that plied the oceans and inland waters, and ferries that carried passengers and sometimes their automobiles around the Bay Area and occasionally as far as Sacramento. These two modes had different hubs at different times.

In terms of oceangoing freight, San Francisco was, from the 1850s through the 1930s, one of the great port cities of the world. By the time the Bay Bridge was built, however, the dominance of the Port of San Francisco was beginning to erode; by the 1960s Oakland was the clear leader in port activities, chiefly because Oakland was linked to good rail and truck routes while San Francisco was not. Port development in Oakland was hampered throughout the nineteenth century by uncertain ownership of land at the waterfront. An 1892 U.S. Supreme Court decision confirmed that most of the waterfront was owned by the city of Oakland, a decision that removed the last major impediment to development there. The Oakland Harbor was expanded during American involvement in World War I. Then, in 1927, the city of Oakland created a separate port department (now the Board of Port Commissioners) and the modern Port of Oakland was created.2

During the decade between 1921 and 1931, the ports in Oakland and San Francisco both experienced explosive growth in commercial shipping, although the pace of growth favored Oakland. Prior to 1927 (when the Port of Oakland was formally organized), shipping tonnage in San Francisco more than doubled that in Oakland. By 1921 the gap had narrowed: Oakland handled about three-quarters the tonnage of San Francisco. Oakland’s port would continue to outgrow San Francisco’s through World War II before overwhelming it during the 1950s and 1960s.

The Bay Bridge did not directly affect the decline of shipping in San Francisco or its ascension in Oakland; that trend is best attributed to improvements in freight rail connections in Oakland and the emergence of land-intensive transshipment methods, both of which worked against the pinched-in port in San Francisco. As discussed later, however, the Bay Bridge did revolutionize trucking in the Bay Area, which was one major part of the transformation of cargo handling. Any oceangoing shipment that was partially intended for San Francisco, for example, could, after construction of the Bay Bridge, be easily transported to the city of San Francisco by truck from Oakland, something that was impossible before the bridge.

Another important part of shipping in the Bay Area before and just after the Bay Bridge was built was the use of the region by the military. It is difficult today to imagine the Bay Area in 1930, when it was one of the most important military hubs in the United States. Following the end of the Cold War, the military has nearly abandoned the Bay Area, leaving only small pockets of high-tech activity still in place. In 1930, however, the region was filled with big and important bases. The Army was well represented with its Presidio of San Francisco (the headquarters to the Fourth Army and home to thousands of soldiers), as well as Fort Mason, and (later) the Oakland Army Base, both important quartermaster facilities. It was the Navy, however, that had a huge presence in the Bay Area around the time of construction of the Bay Bridge, including a large station on Yerba Buena Island (to be joined in the later 1930s by an even larger station on man-made Treasure Island), huge air stations in Sunnyvale and Alameda, major ship construction and repair facilities at Mare Island in Vallejo and at Hunters Point in San Francisco, a supply station in Oakland and another near Stockton, and miscellaneous smaller facilities scattered throughout the Bay Area.

In the 1920s it was not at all clear that San Diego was going to win its long contest with San Francisco for supremacy in naval matters. In the late 1920s San Diego and San Francisco and, to a lesser degree, Los Angeles, vied to be the center of U.S. Navy activities on the Pacific coast. The Navy for its part was content to let the competition go forward, exacting increasingly generous concessions from the host communities.3 The outcome remained uncertain while the Bay Bridge was being planned, a fact that actually delayed construction of the bridge.

With so many active and proposed military bases around the Bay, the War Department jealously protected sea lanes for Navy and Army ships as well as port facilities on the East Bay and in San Francisco, some of which it eyed as potential military bases. The War Department objections were the principal reasons why local interests were unable to build a bridge during the 1920s, when Bay Area interests studied the project in great detail. It was not until the intervention of President Herbert Hoover in the early 1930s that the region and the state overcame these War Department objections.

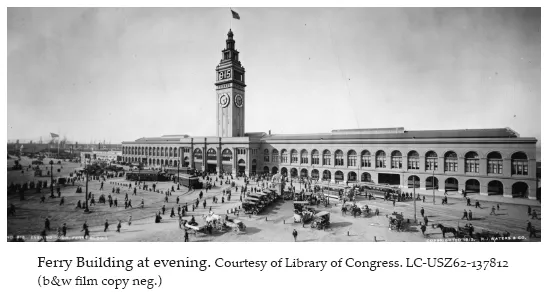

A third important element of navigation prior to construction of the Bay Bridge was the development of a comprehensive and integrated system of passenger and vehicular ferries. In retrospect, we can see that these private ferries did for the Bay Area in the 1920s what would have been accomplished more cheaply and more effectively by the Bay Bridge, had it been built during that decade. As discussed later, there was an exploding suburbanization of the Bay Area population during the 1920s, facilitated by growth of interurban trolleys and highway-based automobile and truck traffic. The interurban and highway systems were quite efficient for their time in every respect except one: they could not go directly across San Francisco Bay. In time, this barrier would be conquered by the Bay Bridge. During the 1920s, however, the best solution available was to carry these hundreds of thousands of passengers and automobiles across the Bay by ferry boat.

As part of early state planning for the Bay Bridge in 1929–30, the California Division of Highways conducted an exhaustive study of passenger and vehicular ferry use in the Bay Area between 1915 and 1929. There were two compelling reasons to complete this study. First, the extensive use of ferries, particularly vehicular ferries, provided a justification for building the bridge, what transportation planners today call the “purpose and need” for the project. Second, and perhaps even more important, the state saw ferry fees as a rough estimate for the income it could count on to repay construction loans for the bridge. In short, the transfer of ferry fees to bridge tolls was seen as a possible, perhaps even primary, source of revenue to repay loans for the bridge.4

The raw numbers and trends in ferry use clearly supported the purpose and need for the bridge. The unmistakable trend between 1915 and 1929 was a decline in passenger-only ferry use and a huge increase in automobile ferry use. Passenger-only use was linked to the interurban trolley system; in other words, the passengers arrived at the ferry site via an interurban. This use, while very large throughout the period, declined 10 percent over the fourteen years of the study, from 38.75 million passengers in 1915 to 35.92 million passengers in 1929. Vehicular ferry service followed a much different trajectory. In 1915 1.75 million passengers rode the ferries with their cars. In 1929 that number was 10.17 million, an increase of more than 600 percent. By 1929 passenger-only ferry use still outnumbered vehicular ferry use by about three to one, but that gap was closing quickly.

The growth in vehicular ferry use, of course, correlated directly with the increasing automobile registration and the development of good highways, discussed later under the chapter on highway transportation. It might also be explained by improved levels of service during the 1920s, as the Golden Gate Ferry line came to dominate vehicle ferry service in much the same way that its parent corporation, the Southern Pacific Railroad, dominated freight and passenger rail service. Prior to World War I ferries would accept automobiles only as space permitted. In 1920 however, Aven Hanford organized the Golden Gate Ferry line, with the specific mission of providing transport for automobiles. The line initially ran between Sausalito and San Francisco but quickly spread to connect San Francisco to various locations in Marin, Alameda, and Contra Costa Counties. The Southern Pacific Railroad had ventured into automobile ferry service on its own but in 1929 bought out the Golden Gate Ferry line operation, achieving a near monopoly on this service.5

Although the Bay Bridge had no specific navigational function, navigational issues would dominate debate about the bridge throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s. Most discussions focused on the need to avoid blocking access to the emerging Port of Oakland. The need to preserve shipping lanes to Oakland and to nearby military bases led to some of the most dramatic engineering challenges in designing the bridge.

The single most dramatic and direct effect of building the Bay Bridge was the crippling of ferry service between the East Bay and San Francisco. This service was alive and profitable before the bridge was built, but virtually disappeared after 1936, not to be revived for more than half a century.

Mass Transit Interurban Rail Service before the Bay Bridge

At the time the Bay Bridge was built, commuter rail lines in most of the United States were called interurban rail lines, or simply interurbans. The term referred to a function rather than a type of rail car. The interurban system of the Bay Area at the time was the functional equivalent of the modern Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) rather than, say, the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni). The interurbans, as the name implies, connected different urban areas, much as BART today connects disparate communities in several Bay Area counties.

Mass transit developed differently in San Francisco than elsewhere in the Bay Area. The street railway system in San Francisco was intra-urban: it was designed to move people within that city, with limited connectivity with systems outside the city of San Francisco. The trolleys and cable cars existed to serve the people of San Francisco. By 1930 most of the mass transit network in San Francisco was municipally owned; only the Market Street Railway remained in private hands. Ridership on the San Francisco railways peaked in the mid-1930s but declined rapidly during the remainder of that decade.6

East Bay interurbans, by contrast, were privately owned at the time the Bay Bridge was built and existed primarily to move workers to and from the East Bay suburbs and San Francisco. The interurban system had always operated in conjunction with privately owned ferry lines, with each rail line owning its own ferries. In a sense, it is a somewhat artificial distinction between navigational aspects of the ferry system and the mass transit aspects of the interurbans: the two were simply different modes within an integrated network.

The concept of an integrated rail-ferry service began with the Central (later Southern) Pacific Railroad in the nineteenth century. The Southern Pacific had provided some type of passenger rail service in the East Bay since the 1860s and began integrated interurban and ferry service from the Oakland Mole in the 1880s.7 Its system was electrified in 1911 and provided passenger interurban-ferry connections via the Oakland Mole as well as a mole on Alameda Island. At the time of its electrification, the Southern Pacific’s interurban lines from the Oakland Mole included two Oakland lines, two Berkeley lines, and a San Leandro line; there were two lines in Alameda leading to the Alameda Mole.8

Although the Southern Pacific was first to provide service, it was the Key System that came to dominate interurban service by the time the Bay Bridge was built in the mid-1930s. The Key System was assembled by Francis Marion Smith, often called “Borax” Smith, and one of the more interesting entrepreneurs in California history. Born in Wisconsin in 1846, Smith left for the American West at the age of twenty-one. He and his brother began mining borax in Nevada in the early 1870s. He established a huge borax empire in the Death Valley region of California and eventually owned mining properties throughout the world. In the 1920s he expanded his empire to include real estate development in the San Francisco Bay Area and his Key System was initially developed to offer interurban access to his East Bay real estate holdings.9

Smith and his partners and successors assembled the Key System from existing steam lines as well as through new construction. Most of the system had been electrified by the turn of the twentieth century. Like the Southern Pacific, the Key System maintained its own fleet of ferries. The Key System ferries docked at the grand Key System Mole, which was immediately south of the future locations of the toll booth and Oakland touchdown for the Bay Bridge. The Key System Mole reached farther and farther into the bay over time. At the time the Bay Bridge was built, the Key System Mole extended nearly halfway between the Oakland–Emeryville shoreline and Yerba Buena Island. The elegant ferry terminal structure at the end of the mole was destroyed in a massive explosion in 1933, while the Bay Bridge was under construction. The ferry house was rebuilt with mundane steel buildings.

By the late 1920s there were eight major Key System lines, extending to Piedmont, Claremont, Berkeley, and various parts of Oakland. The system also included light trolley service that fed into the heavier interurban lines.

As noted, Smith built the Key System chiefly to provide access to land he owned and wanted to subdivide. In 1927 Smith and his Key System partners filed for bankruptcy for the Key System but held on to their far more profitable real estate operation. San Francisco banking interests, led by Alfred Lundberg, reorganized the Key System and operated under that name until abandoning the system in the 1950s.10

The popularity of the interurban commute and associated real estate development worked together to develop a settlement pattern that, somewhat ironically, would be used to justify construction of the predominantly automobile-ori...