![]()

CHAPTER 1

JAYHAWKER BEGINNING: ILLINOIS TO COUNCIL BLUFFS

THE GOLD SEEKERS WERE “well equipped with oxen, wagons and provisions, high hopes and buoyant spirits. . . . Remember how jovially these ardent explorers used to sing the familiar refrain ‘Then Ho! boys, Ho! and to California go; There’s plenty of gold in the world untold, On the banks of the Sacramento’” (Daily Iowa Capital 1896).1

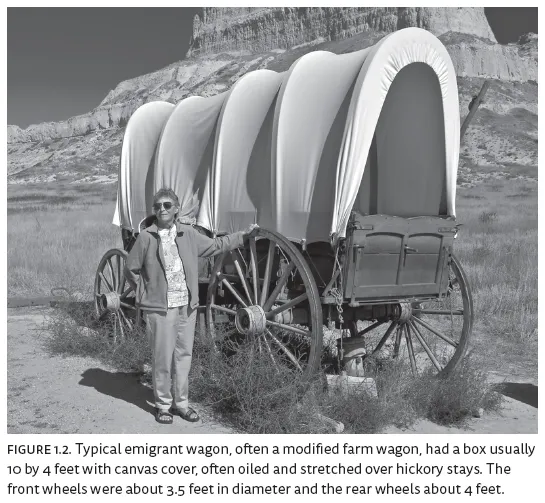

On April 1 (the day to send someone on a “fool’s errand”), four fat oxen stood patiently before a prairie wagon in front of the Colton Mercantile Store in the western Illinois town of Galesburg while Sidney Edgerton, John Cole, and seventeen-year-old John Colton loaded supplies into the wagon that would become their home for the arduous cross-country trip to the California goldfields. John Colton remembered their sendoff years later:

Crowds of friends gathered to wish the gold-seekers Godspeed. All wore smiles, and bits of humor of the time mingled in the conversation, but behind it all there was a full sense of the seriousness of the undertaking. . . .

Amidst the smiles and farewells of friends the church bell began to toll. As the party turned and looked in that direction they saw the village wag in the belfry. . .and as the men drove away, thought it fit and proper that he should toll the bell, as many never expected to see the gold-seekers again. They expected them to lose their scalps on the plains long before they should reach the region of gold. But the adventurers did not view the omen so seriously. One of them looked back and smiled. “It is April first—All-Fool’s Day!” (De Laney 1908, 100–101)

The lure was gold—the siren’s call—tempting men from across the nation to rush to California for easy riches, adventure, a better life—a fool’s errand. The New York Herald spread the news to the whole world in the fall of 1848: “It is beyond all question that gold, in immense quantities, is being found daily in this [newly acquired] part of our territory. . . . Every vessel which anchors in the neighborhood of California, is immediately deserted by her crew. . .affected with the mania. . .of gathering the rich material.”

The Oquawka Spectator, read in the western Illinois towns of Knoxville, Galesburg, and Monmouth, trumpeted on November 28, 1848: “One man dug twelve thousand dollars in six days and three others obtained in one day thirty-six pounds of the pure metal. Two months ago, these stories would have been looked upon as ludicrous, but they are now common occurrences.”2

In December 1848, an official report and a small tea caddy containing gold dust and nuggets arrived in Washington, DC, from California.3 James Marshall had discovered seemingly limitless and easily obtainable gold on January 24, 1848, in the Sierra Nevada foothills of Mexico’s Alta California. Nine days later, the whole of California became part of the United States with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago—part of the spoils of the Mexican-American War.

The world went wild when the golden contents of the tea caddy were put on display. “The value of the gold in California must be greater than has been hitherto discovered in the old or new continent,” extolled the Washington, DC, Daily Union on December 8, 1848 (Bieber 1937, 126). From this little tea caddy erupted the largest voluntary mass movement of people the United States had ever witnessed—the California Gold Rush.

The torrent of humanity started west when men from every hamlet, from Maine to Iowa, reacted to the news of easy wealth. The frenzy was fueled by newspapers such as the Oquawka Spectator that reported on March 14, 1849: “Nearly every steamer passing. . .seems to have on board more or less persons on their way to the gold regions. The fever is decidedly on the increase. Almost every town in the country will be represented in California. . . . Lawyers, doctors, editors, preachers, painters, mechanics of all kinds and farmers alike are pondering over the matter, and some of them packing up their duds for a start.” Earlier, on February 7, the Spectator reported, “The great attraction, however, of late weeks has been California. This is the El Dorado of avaricious expectation. The news comes that $40,000 are taken out daily from the gold washings there. Such tidings turn some heads hitherto reported sound.”

A young man visiting relatives near Monmouth, Illinois, read these stories and was infected by the hysteria. William Birdsall Lorton decided “on going to California, every body talking of going, gold feever rages through out the Country. Commence buying thing[s] such as: spades, shovels, & tinware” (January 10, 1849). He responded to the following announcement in the Oquawka Spectator that all “who intend going to California in the spring by the overland route, are requested to meet” to organize the expedition (January 31, 1849).

Years later Jayhawker Charles Mecum (1878) wrote to his comrades about their departure: “A large party of young robust men,—well equipped, bade farewell to home and friends on that eventful 5th of April, 29 years ago:—buoyant with high hopes of the future: our goal the land of gold. Of our slow and tedious march for weeks through mud and mire—of our dances, our shooting matches, you all know.”4

Jayhawker Urban A. Davison wrote in 1899: “Everything is fresh in my mind that transpired from the time we first left Galesburg and our parints & friends came out and campt with us the first night. . . . Our Hearts was light and gay and full of fond Hop[e]s. little did we think [of the trials] that we would Have to under go before we reached the land of Gold as we never Had campt out and never new what it was to be in need of or deprived of any thing that we desired.” Sheldon Young was more brief in his diary: “Started on our trip for the gold regions · had pleasant weather but muddy roads” (March 18, 1849).

Dr. Ormsby, who traveled in the same train on the Southern Route south from Salt Lake City as did the Platte Valley Jayhawkers, summed up the mass movement:

This emigration may be regarded as one of the greatest anomalies in the history of man. In enterprise and daring, it surpasses the crusades, Alexander’s expedition to India, or Napoleon’s to Russia. These originated with Potentates and religious enthusiasts—were supported by the combined wealth of nations, and urged forward by the power of Kings, Emperors, Pontiffs. . . . This is the spontaneous exhibition of the enterprise and daring of the American character. . . . Acting on obedience to no political power—urged on by no religious zeal, he is actuated solely by his love of adventure, and his love of gold. (in Bidlack 1960, 37)

Over countless centuries, famine, flood, and war have coerced mass migrations of people, but this western migration was different: it was caused by personal choice.

“The compulsion to see what lies beyond that far ridge. . .is a defining part of human identity and success. . . . Perhaps its foundation lies within our genome,” wrote David Dobbs (2013, 50). He continued, saying a variant of the gene DRD4-7R is tied to “people more likely to take risks; explore new places. . .and generally embrace movement, change, and adventure and is found in about 20 percent of the human population.” Maybe our Jayhawkers were some of those spurred by “curiosity and restlessness,” to seek “both movement and novelty.”

The environment in North American culture was ready for this burst of movement, change, and adventure. The nation had just acquired over 545 million acres of land after the war with Mexico, explorers had mapped routes to the West, mountain men had probed this wilderness, and early emigrants had successfully settled in distant Oregon. A fusion of nature (genes) and nurture (culture) was ignited by a little tea caddy full of gold.

The Gathering

On March 14, 1949, six weeks after the Oquawka Spectator published its notice “to take measures for organizing the expedition,” it announced the starting date:

HO! FOR CALIFORNIA

All persons belonging to Capt. Findley’s company are hereby notified to be in readiness to start for California by the 26th of this month. It is thought best to travel in companies of six wagons through to St. Josephs, Mo. By order of the Captain.

John Colton’s father, Chauncey, had intended to have his teenage son travel with Findley’s company. A letter written by one of the train managers said, “I made the necessary arrangement for his [John’s] team and sent word to you to that effect at the time. . . . Yours was the only team I had any positive knowledge of as going from Galesburg, and from that fact I could make no arrangement for any other. Yours therefore will be the only team expected from your place” (Brockelbank 1849). At the end of this letter in John Colton’s hand is this note: “This was the Company I intended to start with but we formed with Knoxville & others.” At least eighteen men who became part of the Knox County wagon train had planned to go with Findley and later tried to catch up to him or convince him to change his plans and merge with the Knox County train. A Findley train member wrote, “The Knoxville teams have not joined us, nor will they. After we crossed the [Mississippi] river at Burlington a delegation from them overtook us, for the purpose of persuading us to abandon the idea of going to St. Jo., stating that it was their design to make a direct move to the Council Bluffs, and wished us to do the same” (W. [Newton Wood] May 16, 1849).

The company became known as “Findley’s lightning train from Oquawka” because of the rapid pace it set. “It is said to be the quickest trip ever made by ox teams” to Fort Laramie, boasted H. M. Seymour. “On the 12th day of August [the Findley train] arrived at the Gold Diggings in California,” six months earlier than the Knox County boys who became the Death Valley Jayhawkers (W. [Newton Wood] June 5, 1849; Seymour June 5, 1849; Findley August 16, 1849).

John Colton wrote his father when he was about forty miles west of Burlington, Iowa, on April 15, 1849:

The Ferry Boat came over [the Mississippi River] with the Knoxville Teams which we have joined and are going through with as Capt Findly would not go to Council Bluffs & St Joseph was chuck full. we have 18 teams and we think that we are strong enough to go through when we started from Burlington. each waggon put in $1. per yoke to bear expenses to Council Bluffs but our Team is going to seperate on account of feed being so high. We think that we can get along cheaper to go 2 Teams together.

As it turned out, these teams did not separate, but his statement makes clear John’s wagon and the Alonzo Clay mess (with whom John rendezvoused at the Clay farm) were not originally part of the Knoxville group, nor were they contemplating staying with that group. Thus, the claim made in the Death Valley Magazine in 1908 that young John Colton had organized a train of twelve wagons is inaccurate (De Laney 1908, 101).

In 1888 John described his start for the goldfields to a reporter:

I was a lad of 16 [17] in 1849 when the gold fever broke out,. . .and it was not long before I had the disease in its most malignant form. I lived with my parents in Galesburg, Ill., and what was my delight one fine spring day to hear that a party had been formed to make the trip to the Golden Gate. I soon managed to get my name enrolled as one of the company, and a sturdier set of young fellows never packed up their little plunder and set out in search of their fortunes.

As afternoon waned on April 1, 1849, John Colton’s mess traveled three miles from Galesburg to the Clay farm, where they joined Alonzo Cardell Clay (twenty-one), “Deacon” Luther A. Richards (thirty), Charles B. Mecum (twenty-six), and Marshall G. Edgerton (thirty-eight), who were the men in wagon number two, as Colton called it years later. All these men became Death Valley Jayhawkers. “At Clay’s they met their first disappointment and were given an idea of what the traveler in those days might expect in the way of delays. They had scarcely pitched camp at Clay’s when a blinding rainstorm set in. For five days and nights it continued with unabated fury. The men were only three miles from home, but they would not return. They had said they would return with the gold dust, and would not now show their faces even for a brief spell without the yellow metal” (De Laney 1908, 101).

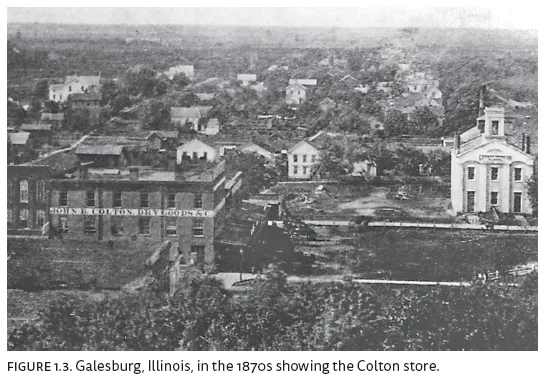

Galesburg was a well-established town by 1849, having been settled in 1836 with a dream of George Washington Gale to bring a civilized, educated eastern village to the sod prairie of the “Far West” “through a system of mental, moral and physical education.” The town has always been known for its educational institutions; it also became an active depot on the Underground Railroad.

Galesburg, with about four hundred inhabitants, impressed William Lorton, an outgoing and inquisitive twenty-year-old New York City house painter who was visiting cousins near Monmouth, Illinois, in late 1848: “pritty town, every thing looked clean. . . . Fine church, beautiful finish. Academy, college & schools at Galesburg. Fine society at this place. Academy brick, paint cream color. Cupalo on to[p]” (October 7, November 19, 1848). Several members of what became the Knox County Company wagon train were from the Knoxville area, the heart of flourishing farm country. Although Knoxville, three miles southeast of Galesburg, was the oldest town in the county and the county seat, it was uninspiring to Lorton.5 Only the county courthouse, with its “steeple on top, 4 Ionic collums, brick & morter,” was worthy of his attention (October 7, 1848). The wealth was in the surrounding farm and grazing land. For instance, Asa Haynes, later elected captain of the Knox County Company wagon train, had a thousand acres of land, had built a brickyard and sawmill by 1840, and had a twelve-room, two-story brick house with the largest frame barn in the county. He married Mary Gaddis in 1830, and she bore eight children (Ellenbecker 1993, 5).

The start of this momentous trek in search of gold was not propitious—mud, rain, and swollen streams caused slow progress. Lorton summed up the weather—“bad going”—as teams collected near Monmouth to form a train to the goldfields. From April 3 through April 7, he said, “Rainey &...