- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Short History of Las Vegas

About this book

Today's Las Vegas welcomes 35 million visitors a year and reigns as the world's premier gaming mecca. But it is much more than a gambling paradise. In A Short History of Las Vegas, Barbara and Myrick Land reveal a fascinating history beyond the mobsters, casinos, and showgirls. The authors present a complete story, beginning with southern Nevada's indigenous peoples and the earliest explorers to the first pioneers to settle in the area; from the importance of the railroad and the construction of Hoover Dam to the arrival of the Mob after World War II; from the first isolated resorts to appear in the dusty desert to the upscale, extravagant theme resorts of today. Las Vegas—and its history—is full of surprises. The second edition of this lively history includes details of the latest developments and describes the growing anticipation surrounding the Las Vegas centennial celebration in 2005. New chapters focus on the recent implosions of famous old structures and the construction of glamorous new developments, headline-making mergers and multibillion-dollar deals involving famous Strip properties, and a concluding look at what life is like for the nearly two million residents who call Las Vegas home.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Short History of Las Vegas by Barbara Land,Myrick Land in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Grab a bagel and coffee at a sidewalk cart in lower Manhattan and head out to explore the world in a single day.

“There is no place like it. It is literally a beacon of civilization. Peering from space at their cloud-speckled blue and blood-rust planet, astronauts make out the lights of Las Vegas before anything else, a first sign of life on earth. The sighting is apt. The city’s luminance draws a world. More than 50 million people journey to it every year.”—Sally Denton and Roger Morris in The Money and the Power: The Making of Las Vegas and Its Hold on America 1947–2000

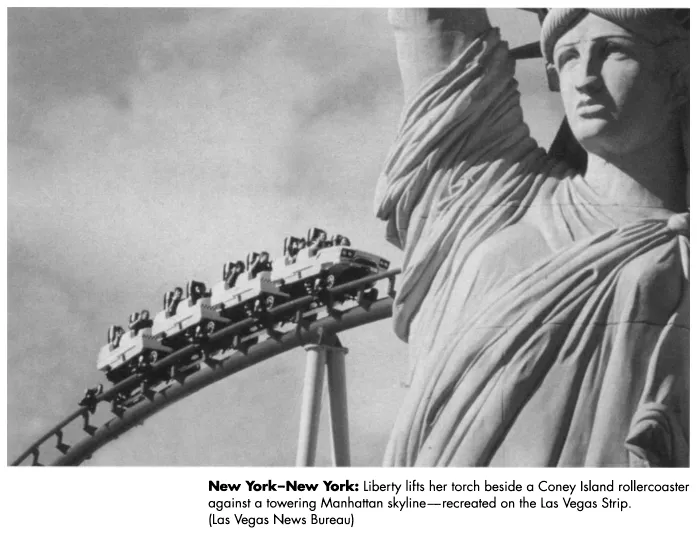

Walk under the Brooklyn Bridge and down the street to take an elevator to the top of the Eiffel Tower. Invade an Egyptian pyramid to view excavated treasures from King Tut’s tomb. Stroll beside a Venetian canal and hire a gondola, complete with singing gondolier, and relax on the water beneath a blue Italian sky. Or maybe you’re ready for lunch at that outdoor café in the Piazza San Marco. You’d still have time for afternoon visits to a couple of art exhibits—French impressionist paintings or abstract sculpture—and a quick excursion to Red Square, to sip a little Russian vodka before dinner.

A Las Vegas fantasy? You bet it is! But millions of visitors from everywhere build their own fantasies around the lavish movie-set replicas along the Las Vegas Strip. Where else could they sample so many dreams in such a short time? Where else could they take a long walk past King Arthur’s Camelot, the Statue of Liberty, several ornate palaces, and an erupting volcano—all without leaving the sidewalk? Even local Las Vegans often venture into the crowds.

“We don’t spend much time on the Strip, unless we have visitors,” said Jill Fielden, who called herself “a traditional mom” when we talked at her suburban home. Most of the time, she was busy enough in her role as wife of Dr. Scott Fielden, a Las Vegas–born anesthesiologist, and as mother of their three pre-teen children. The Fieldens live in Summerlin, a master-planned community in the northwest corner of Las Vegas, annexed to the city in 1987. Their quiet street in the Chardonnay Hills division, with views of rugged mountains in the distance, is just ten miles from the Strip—but it seems a world away.

Jill’s mother, Reno artist Carol Johnson, loves to travel. So, when Jill planned a family birthday party for Carol, a round-the-world theme seemed ready-made.

“I’ll never forget that birthday party,” Carol recalled later. “We went around the world without any airport security hassles and no packing and unpacking.” Giving a detailed account of the party’s progress through European resorts and the Big Apple, she marveled at the memory. “And we did it all in one day!”

Her daughter’s comment: “We couldn’t have done THAT on the Concorde!”

As she spoke, planeloads of visitors were arriving at McCarran International Airport, just a few blocks away from the neon playground. Vacationers and gamblers, seekers of entertainment and seekers of luck, they still come to explore the pleasure palaces. Scattered among them are some who come to stay—and they keep on coming.

These new Las Vegans keep the city running and growing, not only for the millions of visitors but for their own families and descendants. Their taste for adventure has brought them here for reasons that separate them from the other risk-takers. They’re here to build houses, open new businesses, treat hospital patients, teach schoolchildren, or look for jobs in the casinos. They plan to become part of the city . . . maybe for a lifetime. Beyond the glitter of the casinos, these newcomers discover a rich history that goes back to prehistoric times. Perhaps they’ve inherited some of the frontier spirit of the early settlers in the Las Vegas Valley.

As Las Vegas approached its centennial birthday celebration—May 15, 2005—the city remembered the area’s earlier settlers and explorers. Mayor Oscar Goodman was making plans well ahead of time. In the summer of 2002, he revealed a few details:

Las Vegas in the 1930s: “Relatively little emphasis is placed on the gambling clubs and divorce facilities—though they are attractions to many visitors—and much effort is being made to build up cultural attractions. No cheap and easily parodied slogans have been adopted to publicize the city, no attempt has been made to introduce pseudo-romantic architectural themes, or to give artificial glamor and gaiety. Las Vegas is itself—natural and therefore very appealing to people with a very wide variety of interests.”—The WPA Guide to 1930s Nevada

“We’re gonna kick it off on May 15, two thousand FOUR,” he said. “We’ll have a full year of ceremonies leading up to the birthday itself, then we hope to have the biggest birthday bash in the history of the world.” The mayor doesn’t spare superlatives when talking about his city. “We have a centennial committee and I’m the chairman of it,” he explained. “We have folks from the private sector and public sector and various representatives of special interests in the community, all banding together to make it an unforgettable experience.”

Casinos on the Strip, officially outside the city, were making their own ambitious plans for 2005, but the mayor focused his attention on the actual birthplace of Las Vegas. “The centerpiece for our celebration will be the new Las Vegas Springs Preserve,” he said. “It’s going to be our Central Park. The Las Vegas Valley Water District has been working on it for years—and it will open on the city’s birthday.”

The Watering Place

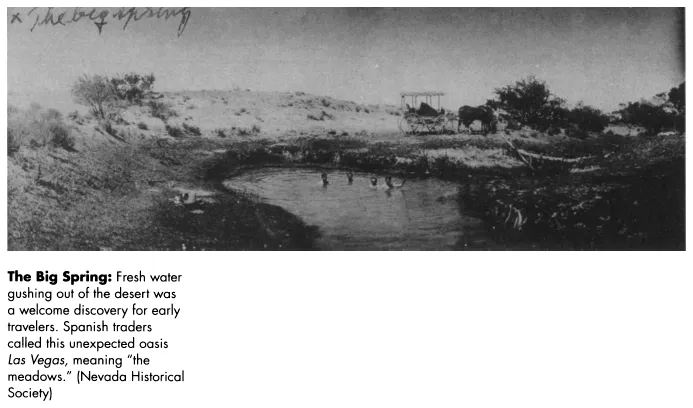

Long before it was even a town—a railroad stop established in 1905—the place was called Las Vegas. Spanish-speaking traders from New Mexico, on their way to California in 1829, strayed from the Old Spanish Trail blazed in 1776 by Spanish missionaries. When they came upon springs of fresh water gushing out of the desert, they gave this unexpected oasis a Spanish name, Las Vegas, “the meadows,” and added it to their maps. Rafael Rivera, an adventurous young Mexican scout with Antonio Armijo’s trading party, is named by most historians as the first European American to visit the Las Vegas oasis, but he and his companions were not the first people to drink from these springs.

“Probably no other metropolis in the world could boast of a resident populace who can remember when their town was founded.”—Stanley W. Paher, Las Vegas: As it began—As it grew

Thousands of years before it had a Spanish name, the valley that became Las Vegas attracted thirsty travelers. As early as 11,000 years ago, some archaeologists believe, nomads camped at Tule Springs, just two miles west of modern Fremont Street. Crude stone tools and charred animal bones found in the area have been analyzed in twentieth-century laboratories to provide clues to the origins and survival methods of a forgotten people.

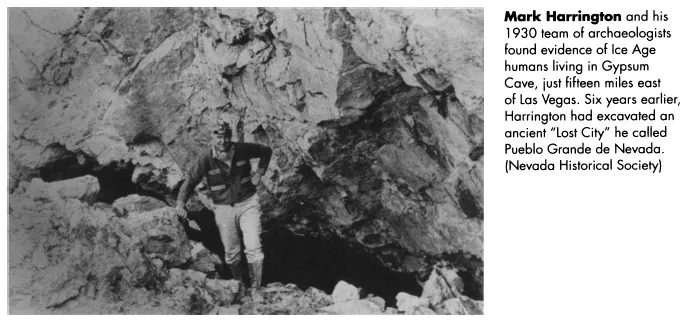

A vivid, imaginative portrait of these “first-comers” and their environment was written more than a half-century ago by archaeologist Mark R. Harrington, leader of several landmark Nevada excavations in the 1920s and 1930s. After he became curator of the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, Harrington summarized the findings of twelve years of field work in a popular leaflet published jointly by his museum and Nevada’s Clark County Historical Society.

“Ten or fifteen thousand years ago,” he wrote, “at the close of the Pleistocene or Ice Age, the region we call southern Nevada, now so barren, was green and well-watered. Everlasting snow capped the higher mountains, from which flowed glaciers, living rivers of ice; blue lakes of fresh water dotted the lower valleys; streams were frequent where now only dry washes remain.”

“The interpretation of ancient rock writings has intrigued many people; and there are wild speculations on the meaning of the symbols. Most of the interpretations, though, are mere romantic conjectures.”—Emory Strong, Stone Age in the Great Basin

Harrington described a lush, wet landscape inhabited by huge animals, now extinct: mammoths, native horses and camels, giant buffalo, and “lumbering, stupid ground sloths, looking like imbecile, long-tailed bears.” He imagined these vegetarian animals grazing along with elk, deer, mountain sheep, and antelope “not greatly different from those which still survive,” threatened by meat-eating wolves, mountain lions, and saber-toothed tigers.

“Such was southern Nevada when man first set eyes upon it and found it good. Probably drifting in small bands from the north, where their forebears had crossed to Alaska from Siberia, these copper-hued, black haired discoverers of America hunted the grass-eaters and fought the flesh-eaters where never man had set foot before.”

Like an archaeological jigsaw puzzle, built on scientific details mixed with speculation, Harrington’s vision of the first Nevadans became more and more specific. He described their weapons and tools, supporting his reconstructed picture with evidence found buried in the desert.

“What these early people looked like we cannot say,” he wrote, “for their bones have not yet been found; but we know they hunted the strange animals of the past and left the charred bones of elephants and camels slain for food in the ashes of their campfires; while in caves, their temporary stopping places, their weapons have been found buried with the remains of the ground-sloth. Traces of their camps, with heavily weathered implements of stone, may still be seen on the former shorelines and headlands of streams and lakes long dry and forgotten, in districts where man cannot live today for lack of water.”

In the Valley of Fire: “The rocks have been stacked, as though by a blackjack dealer, into huge sheets of carbonate rocks. This is the Overthrust Belt. The pressures from titanic forces have shoved rocks over rocks and stacked them into geologic puzzles.”—Bill Fiero, Geology of the Great Basin

When the water dried up, over a period of several thousand years, these nomads moved on, looking for food wherever they could find it. The archaeological trail becomes a little blurred between 9,000 and 4,000 years ago, but there’s plenty of evidence of early human existence in the Las Vegas area. Archaeologists have named these prehistoric people for the places where their traces were first found: Tule Springs, Lake Mohave, Pinto Basin, Gypsum Cave.

“Las Vegas has had a curious history of exodus. In earliest times, it was peopled by the stone-culture Anasazi Indians. . . . They were agricultural Indians who learned the science of irrigation and raised crops of beans, squash and cotton. They also mined salt and turquoise which were traded with nomadic Southwest Indians. Then must have come a time of war, because the Anasazi abandoned their Pueblo Grande and moved to the protection of the almost inaccessible cliffs that over-look Las Vegas Valley. From there, they simply disappeared, leaving behind them an anthropological mystery of why they had left and where they had gone.”—Robert Laxalt, Nevada, A Bicentennial History

Detectives of Time

Just fifteen miles east of Las Vegas, in the Frenchman Mountains, Gypsum Cave became the focus of worldwide scientific interest in the early 1930s when Mark Harrington and his associates announced their discovery of a skull unlike that of any known animal. A few years earlier, Harrington had visited the cave and noticed a deposit of strange animal dung. He knew it wasn’t from a horse. Certainly not a modern horse. So what was it?

Suspecting, hoping, that he might have discovered traces of an extinct animal, Harrington organized an excavation party to begin work in January 1930. Soon after they started exploring, the expedition secretary, Bertha Pallan, found the odd skull in a crevice of the cave. When laboratory zoologists identified it as the skull of a long-extinct ground sloth, Harrington knew he was on the trail of an exciting find. Sloth bones and claws found in the cave confirmed the identification. If the researchers could find evidence of early human presence in the cave at the same time as that of the extinct sloth, they might be able to set an approximate date when these humans visited the cave.

Harrington’s excitement over the sloth discovery soon attracted financial and scientific support from the California Institute of Technology, the Carnegie Institution, and the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles. While these backers waited for detailed reports, the excavators began their meticulous digging, sifting, and recording. A few feet below the surface, they began to turn up traces of campfires, charred baskets, crystal ornaments, and fragments of tools used by early humans—maybe as far back as 1,000 B.C.—but not quite so early as the extinct sloth. The researchers kept on digging.

Finally, after excavating layers and layers of earth, sheep dung, and a rockfall three feet thick, hinting at a past earthquake, the archaeologists found what they were looking for. Eight feet below the original surface, buried underneath a solid layer of sloth dung, they came upon a fireplace and crude tools, convincing them that Ice Age humans had been in the cave about the same time as the extinct sloths. Cautiously, Harrington reported these discoveries as at least 7,500 to 9,500 years old. Years later, radiocarbon dating of Gypsum Cave samples found them much older, a treasury of archaeological evidence preserved in the cave for at least 10,000 years.

Some of the ancient artifacts uncovered by Harrington and his team are still displayed in the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, along with the claws of the prehistoric sloth.

The Basketmakers

Look ahead a few thousand years to about 300 B.C. The climate has changed drastically. Lakes and rivers have dried up, the big animals have long since disappeared, and a hot, rocky desert surrounds the oasis that will become Las Vegas. ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface to the Second Edition: Las Vegas: Fast Forward

- Acknowledgments

- 1 - Great Expectations

- 2 - The Settlers

- 3 - Two Towns Called Las Vegas

- 4 - Gateway to the Dam

- 5 - Politics, Las Vegas Style

- 6 - Inventing the Strip

- 7 - Bugsy and “The Boys”

- 8 - Dark Shadows Over the Playground

- 9 - Mr. Hughes Arrives in Las Vegas

- 10 - The Entertainers

- 11 - Three Tycoons

- 12 - The Grand Tour

- 13 - Big Deals, New Directions

- 14 - Who Lives in Las Vegas?

- Selected Bibliography: More About Las Vegas . . .

- Index