- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Winner of the Mining History Association Clark Spence Award for the Best Book in Mining History, 2017-2018

Brian James Leech provides a social and environmental history of Butte, Montana's Berkeley Pit, an open-pit mine which operated from 1955 to 1982. Using oral history interviews and archival finds, The City That Ate Itself explores the lived experience of open-pit copper mining at Butte's infamous Berkeley Pit. Because an open-pit mine has to expand outward in order for workers to extract ore, its effects dramatically changed the lives of workers and residents. Although the Berkeley Pit gave consumers easier access to copper, its impact on workers and community members was more mixed, if not detrimental.

The pit's creeping boundaries became even more of a problem. As open-pit mining nibbled away at ethnic communities, neighbors faced new industrial hazards, widespread relocation, and disrupted social ties. Residents variously responded to the pit with celebration, protest, negotiation, and resignation. Even after its closure, the pit still looms over Butte. Now a large toxic lake at the center of a federal environmental cleanup, the Berkeley Pit continues to affect Butte's search for a postindustrial future.

Brian James Leech provides a social and environmental history of Butte, Montana's Berkeley Pit, an open-pit mine which operated from 1955 to 1982. Using oral history interviews and archival finds, The City That Ate Itself explores the lived experience of open-pit copper mining at Butte's infamous Berkeley Pit. Because an open-pit mine has to expand outward in order for workers to extract ore, its effects dramatically changed the lives of workers and residents. Although the Berkeley Pit gave consumers easier access to copper, its impact on workers and community members was more mixed, if not detrimental.

The pit's creeping boundaries became even more of a problem. As open-pit mining nibbled away at ethnic communities, neighbors faced new industrial hazards, widespread relocation, and disrupted social ties. Residents variously responded to the pit with celebration, protest, negotiation, and resignation. Even after its closure, the pit still looms over Butte. Now a large toxic lake at the center of a federal environmental cleanup, the Berkeley Pit continues to affect Butte's search for a postindustrial future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The City That Ate Itself by Brian James Leech in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University of Nevada PressYear

2018Print ISBN

9781948908290, 9781943859429eBook ISBN

9780874175981PART I

MINING IS LIFE, 1864–1954

CHAPTER 1

UNDERGROUND

THE STORY OF BUTTE’S era of underground mining is usually told as a lusty, rip-roaring tale. Historians typically begin the story with a gold rush, like they do for so many other cities in the West. People had known about gold for decades, but it was only in 1862 that the first diggings opened up in what is now southwestern Montana. Migrants had been traveling across the West looking for gold for more than a decade at this point; the California Gold Rush, which began in 1849, had encouraged a rush mentality, accelerating western settlement. This westward movement was not the mythic frontier later described by historian Frederick Jackson Turner, with people moving successively westward to start their own farms. Instead, mining rushes meant a messy series of migrations that were “widely separated geographically and chronologically rather than a single entity,” as western historian Rodman Paul later put it.1

Nor were mining rushes peaceful. By 1862 southwestern Montana had met the two preconditions to a gold rush. First, violence led to legal agreements between the natives living in each area and the expansionist United States. Second, transportation networks had been built, providing an easier path to and around the area. The rush affected native peoples the most, many of whom had lived in western Montana for centuries. In fact, more than 12,000 people lived in western Montana in 1862, very few of whom were European Americans.2

New people from around the world found their way to the site of each new boom, forming complex communities.3 Enough people had arrived in southwestern Montana—slightly more than 20,000—that in 1864 Abraham Lincoln signed a bill creating Montana Territory. At first, many migrants engaged in placer mining, which involved a simple act—washing gold out of gravels, streambeds, and banks.4

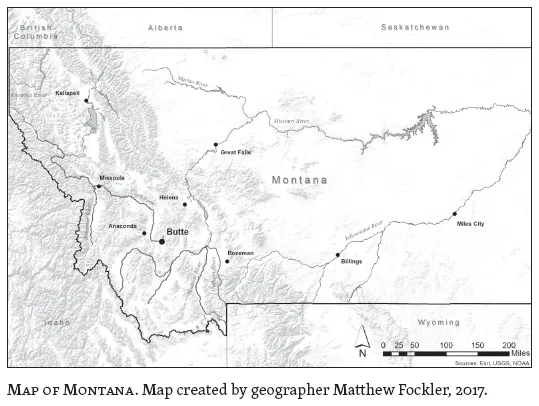

Mining began in the territory’s Summit Valley in 1864. Surrounded by ridges and peaks, this mile-high mountain valley sits just to the east of the continental divide. On the northeastern edge of the valley, prospectors came across a small pit along the Missoula Gulch. The trader who originally discovered the pit, Caleb E. Irvine, found worn elk horns nearby. He thought that perhaps members of a nearby tribe had been mining it, using the horns as picks. In 1864 prospectors William Allison and G. O. Humphries dug even deeper into the pit, setting off more mining in the area. A boomtown named Silver Bow rapidly formed a few miles west of the site. From 1865 to 1867, placer miners would arrive in the spring and summer to mine along Silver Bow Creek. They began a small community of three hundred to five hundred people at the creek’s headwaters. The community gained the name Butte because of a tall nearby landmass. As in most gold rushes, the boom was short-lived. By 1874 the area had lost much of its population. The easy-to-grab gold had played out and the rest was bonded with other minerals, like silver, copper, manganese, and zinc, and hence difficult to separate. The economic panic of 1873 and a gold rush to the Black Hills provided further incentive to leave.5

After experiencing its first boom and bust in just ten years, Butte faced the prospect of becoming a ghost town, but before that could happen silver and then copper rescued the area. The history of mining in Butte thus stands out partly because of its longevity; most mining camps fail to last past their first bust. Butte’s longevity came partly because of its mineral wealth, but also because of the skilled miners who later arrived and made great sacrifices in a hazardous underground, and the intelligent mine managers who capitalized on new discoveries, navigated fluctuating markets, and continually updated mining methods. The result was a dramatically altered landscape and a local culture generated from underground work. Even as mine dangers bound workers together in camaraderie and industrial unions, the mining workplace gave miners a sense of independence. The mines similarly encouraged resilience in community members: they had a sense that most problems, whether industrial hazards, strikes, economic troubles, or outsiders’ attacks, were commonplace occurrences through which the community would persevere. This culture was challenged only in the mid-twentieth century, during an attempt to shift Butte’s operations toward mass mining.

COPPER BECOMES KING

Butte’s underground era began with a silver boom. The processing of Butte’s new silver finds in the 1870s required a lot of capital investment and technological know-how. New corporate investors and skilled miners hence arrived to deal with the district’s complex quartz ores. Revitalization allowed residents to incorporate Butte as a city.6 The city’s wide, southward-facing hill, on which most of Butte sat, would soon make the area famous, but because of copper, not silver. The switch to copper happened partly because of two important figures who arrived in the 1870s.

The first was a second-generation Scots-Irishman, William A. Clark, who entered Butte in 1872. He quickly snatched up mining claims from people who could not figure out how to deal with the hill’s ores. As a city grew around him, Clark obtained an interest in the first mill to process those ores, learned some metallurgy, gained financial backing from eastern interests, founded a mercantile, and, eventually, bought a newspaper to help promote his interests. Favoring skilled Cornish miners and other Protestants, Clark quickly amassed an empire.7

The man who was to become his rival, Marcus Daly, arrived four years after Clark. The Irish-born Daly came as a representative of the Walker Brothers, merchant bankers in Utah. He had already enjoyed a short, but fruitful, career as a practical silver mining man in Nevada and Utah. After suggesting that the Walkers purchase the Alice Mine, he moved to Butte to pursue other properties. Daly had interest in the Anaconda Mine, which had been named for a Civil War metaphor about General George M. McClellan’s plan to surround Confederates and, like a giant anaconda, to squeeze them with his forces. Daly raised capital by appealing to mining magnate George Hearst, who, along with his California partners James Haggin and Lloyd Tevis, was forming a major mining conglomerate, with properties in Nevada, South Dakota, and Utah. As the silver boom died, Daly sneakily bought up surrounding claims because he had located a massive, fifty-foot-wide copper vein in his new purchase: the Anaconda Mine.8

Founded on this initial discovery, the Anaconda Copper Mining Company quickly became the largest corporation in Butte. Both Anaconda and other copper producers raised metal production to great heights, both as a way to gain market share and as a way to offset the major investments needed for lode mining. Low-priced copper thus became available for new uses, like electricity. By the 1890s copper wire had become vital to transmitting electricity, which itself had become a major industry, benefitting Butte’s expanding mines.9 With more Butte miners turning to copper, production from the area’s mines soon overtook that of upper Michigan, which previously had been the biggest copper producer in the United States.10 Daly relied on his fellow Irishmen and other Catholics to work the rich properties. Butte soon became the most Irish city in the United States, with more than a quarter of its population either first- or second-generation Irish.11

Having Catholics, Protestants, and money-hungry industrialists suddenly shoved together in one city meant tension. After Montana became a state in 1889, Clark and Daly fought over the location of the new capital. Daly favored the town of Anaconda, a company town that bore the corporate name that he had established, twenty-six miles west of Butte. Using money from Anaconda’s new investors, the European Rothschild banking family, Daly had built a large smelter to process his ore there. Clark favored a silver boomtown, Helena, for the capital. Clark’s forces slung accusations about Anaconda’s overpowering greed and its brutish immigrant workers, which helped carry Helena to the win. (The enormous amount of money that Clark put into bribing thousands of people likely helped as well, although Daly also used that trick.) In the coming years the two copper barons also battled over a U.S. Senate seat, which Clark desired as a final step to becoming more than just a copper baron, but a famous millionaire.12

In the War of the Copper Kings, as it became known, another competitor entered the fray: Augustus F. Heinze. Trying to take advantage of the intense fracturing of Butte’s ore bodies, Heinze made use of the Apex Law, federal legislation from the 1860s that allowed the owner of a claim to follow a vein of ore as far below ground as it goes, as long as it apexes, or breaks the surface, on that person’s property. Cultivating a populist persona, Heinze wrapped Anaconda up in the courtroom, while his miners, having tunneled into an Anaconda Mine, actually turned to underground fisticuffs with Anaconda’s at one point.13 Anaconda eventually won most of the legal battles, thanks especially to engineer David W. Brunton and geologists Horace Winchell and Reno Sales, who were gaining acclaim for developing a systematic method for geological mine mapping. Working to consolidate all of Butte’s mines, Anaconda eventually wore down Heinze, buying him out for $12 million in 1906. Having gained his Senate seat and making piles of money from an Arizona copper mine, Clark lost interest in Butte, spending most of his time and money outside the state. After besting its top two competitors, the Anaconda Company was victor.14

Victory’s spoils in Butte were not enough for Anaconda. The company briefly became subsumed under the Amalgamated Copper Company, when William Rockefeller and Henry Huttleston Rogers of Standard Oil tried to corner the market on copper. By the time Amalgamated dissolved in 1915, Anaconda had become an industrial powerhouse. It both bought forest around Montana and trespassed onto the public domain so that it could provide logs to hold up its underground mine tunnels. Company management devoted increasing amounts of energy to lobbying state politicians, providing legislators in Helena with drinks and steaks. Beyond buying influence, Anaconda also practiced union infiltration to ensure its workforce stayed in line; it also used cruder coercion, sometimes including gunplay, as it did when company detectives fired on striking miners in 1920, killing two and wounding sixteen.15

Anaconda ran into a burgeoning labor movement on many other occasions as well. Called the Gibraltar of Labor, Butte featured many labor organizations, from the conservative Butte Miners’ Union (BMU), which founded the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), to the more radical International Workers of the World (IWW), who, in the 1910s, were trying to gain a foothold in the area. Butte even elected a socialist mayor in 1914. That year, however, the conservative miners’ union, which had worked hard to protect steady jobs for Irish men in particular, broke apart due to tensions between old and new immigrants, and conservative and radical unionists. An angry mob blew up the BMU hall. Declaring martial law, the governor sent in the Montana National Guard. Anaconda took advantage of the situation, instituting a rustling-card system, which were permits that allowed men to look for work at each mine (hence giving the company more control over who worked where). The company then declared that the union’s closed shop was over because the WFM lacked legitimacy.16

Union organizers continued to stream into Butte because they could see discontent that needed an outlet, but they faced a strong company challenge. The company had political backing because copper was vital, and was needed for bullets and other war matériel. Many immigrants, particularly the Irish, were upset about U.S. entry into the Great War on the side of Britain, which made others in the region suspicious. Socialists, including many Finns, were angry with the company, particularly since it had fired five hundred miners for radical beliefs a few years earlier. The Speculator Mine disaster in June 1917, in which more than 160 men lost their lives in a mine fire, accelerated the tumult. It was not only the worst metal mining disaster in history, but it also triggered a major strike. The supposed initiator of the accident had a German name, and so many Montanans turned against the immigrant workforce and its Irish-German influence. Into this situation entered IWW organizer Frank Little, who was murdered in August 1917. The existence of radical political views among workers continued to seem anti-American during the national Red Scare just after the war ended. Butte remained under martial law until 1921, while the labor movement took years to recover from the scare, both in Butte and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I · Mining Is Life, 1864–1954

- Part II · Working the Pit, 1955–75

- Part III · Feeding the Factory, 1955–75

- Part IV · The Pit Is Dead (Long Live the Pit), 1970–2017

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- About the Author

- Index