Using the metaphor in the quote at the beginning of this section, many attempts at CDS have produced weeds. Those organizations that can repeatedly leverage CDS to significantly and measurably improve targeted outcomes have cultivated effective and fruitful CDS programs.

As described in the “How to Use This Book” section of the front matter, the introduction to each part contains two case studies—one in a community hospital and one in a small office practice. These hypothetical examples (based on synthesized real-world experiences) illustrate what it might look like to follow portions of the guidance presented in the chapters that follow.

You can examine the example(s) most pertinent to your setting before you dive into the chapter details, refer back to them as you review the chapter, and perhaps share the material with others on your team to help them understand the relevant processes and desired outcomes. In both case studies, each text section is introduced by a “Task” that relates to the material presented in the chapters. These headings help make explicit the key points that are being illustrated.

CASE STUDY FOR HOSPITALS: REDUCING POTENTIALLY PREVENTABLE INPATIENT VTE INCIDENCE

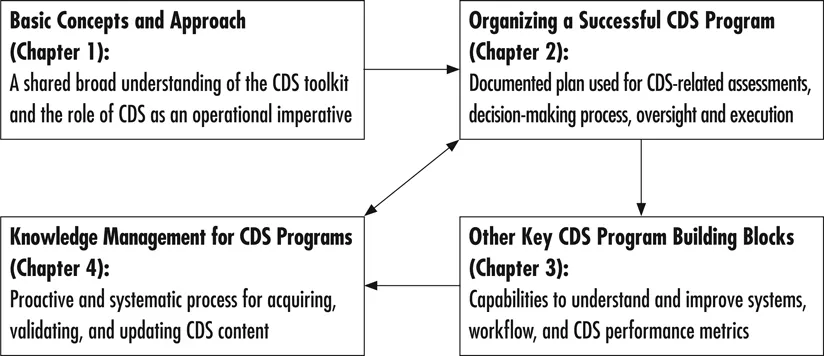

Establish a strong, shared foundation of knowledge for yourself and your team around basic concepts such as the broad CDS definition and toolkit, and CDS’s role as a strategic tool for driving measurable performance improvement. Use this foundation to underpin your efforts to develop successful CDS programs and interventions.

At Grandview Hospital, Mrs. Sadie Adler, a 75-year-old postoperative hip fracture patient, developed a potentially preventable venous thromboembolism (VTE) and then died suddenly as a result. A review of her case at Grandview’s Morbidity and Mortality Conference identified that she had not received interventions (broadly referred to as “VTE prophylaxis”) that might have prevented this condition and tragic outcome.

Hospitalist Dr. Glenda Goldsmith had performed Mrs. Adler’s pre-op evaluation, and after the Morbidity and Mortality Conference, she chose to champion this process improvement (PI) project for the hospital. Dr. Goldsmith understood the challenge was daunting but was fortunate to quickly enlist Grandview CEO Albert LaSalle’s support after presenting this case to the Medical Executive Committee. CEO LaSalle noted that the hospital chose VTE as a quality measure in its contract with Alpha Health Plan and that addressing this issue effectively could also result in a bonus payment to the hospital. In addition, the Joint Commission had just requested that the hospital begin reporting its incidence rate of potentially preventable VTE.

These forces made it logical for Grandview and the Medical Executive Committee to select the improvement of VTE prophylaxis as a key performance goal for the next year. They created a financial incentive program to help ensure adequate attention—among myriad other priorities—to this initiative by pertinent stakeholders.

At the time of this tragic event, Grandview had strong nursing leadership and a physician champion for its electronic health record (EHR) efforts, but the remaining physicians were hesitant to change. The hospital was also fortunate to have IT and quality departments that were engaged and responsive. While Grandview had implemented computerized practitioner order entry (CPOE), at the time of this event it had no house-wide VTE prophylaxis order sets—and the ones it had were scattered among admission and postoperative orders. Standardized risk assessment and prophylaxis selection were virtually nonexistent and clinical care varied widely. Among hospital employees, there was little awareness of VTE as a significant issue, and it was mostly up to individual physicians to order prophylaxis. Also, there were no checks for prophylaxis by nursing or pharmacy, and no regular auditing of VTE rates.

PI leader Goldsmith had been intrigued over the past few years by the promise of clinical decision support (CDS) to improve care processes and outcomes and spent time learning about this subject from journal articles, sessions at medical conferences, and books devoted to the topic. She had been a physician liaison for the CPOE implementation, and in light of Mrs. Adler’s potentially preventable death, saw that there was tremendous opportunity to enhance Grandview’s use of CDS to address VTE prophylaxis and other high-priority conditions. Her CDS studies had convinced her that for Grandview to be successful, it would need to build a robust CDS program that would provide fertile soil for CDS interventions focused on VTE prophylaxis and other key conditions could be developed and maintained over the long term. This would require the sustained effort and collaboration of many stakeholders and new organizational structures and processes. Potentially daunting, but …

Determine and document the who, why, what, how and when of your CDS approach and activities.

Fortunately, Grandview had a strong complement of leaders who shared a vision of quality care and patient safety. These included physician champions in medicine and surgery, a chief nursing officer and nursing executive champion, and a chief financial officer (CFO) who could appreciate the nuanced link between Grandview’s financial health and its core healing mission. Other key quality advocates included the director of pharmacy, and the chief information officer (CIO) and his IT staff. Grandview had recently hired an internist on staff, Dr. Fred Jones, as part-time director of clinical informatics. He had some formal informatics training and was initially engaged to support the hospital’s EHR and CPOE efforts, but he would soon step up to a more central role in Grandview’s improvement efforts.

The recent tragic events—and the attention they drew in various Grandview forums—galvanized recognition in these leaders that they must work together to more effectively leverage their information system to provide better care—not just for VTE prophylaxis, but for the increasing number of clinical goals and quality measures that were becoming important to the organization. They needed a new, but strong and effective, CDS program. The leaders committed early on to engaging the entire hospital on this journey. A key ingredient was to gain commitment from each clinical unit to measure and improve targeted outcomes and to engage in the full lifecycle of CDS interventions to drive this change.

Realizing that clinical, operational and financial outcomes were all-important and inter-related, they made sure that leaders with accountability for all these dimensions were engaged in developing the CDS program and that this effort would likewise be coordinated with other related organizational activities such as committees related to quality and operational improvement.

The CDS Committee was formally established with the support of senior administration. Clinical Informatics Director Jones was the natural choice to chair this committee, and he and Grandview agreed to increase his time devoted to this role (and corresponding compensation) to accommodate the additional important responsibilities. The CDS Committee included members who sat on existing relevant committees within the hospital. Members from the P&T Committee, the EHR Committee, the Patient Quality and Safety Committee and nursing unit directors, as well as senior leadership were represented. Leadership recognized the importance of “cross-pollinating” the committee so that the CDS Committee could both be influenced by and understand the committee’s effect on other aspects of the hospital’s practices and culture. While the committee established its CDS charter and processes/procedures, VTE prophylaxis would be the first focus for the group. It was recognized, however, that this committee could not drive quality improvement (QI) projects itself, so they recommended the formation of a VTE QI Team with whom they would work closely on the specifics related to this condition.

Hospitalist Goldsmith, who had been inspired to become the physician leader in this effort, agreed to lead the VTE QI Team with a nursing unit director as co-chair. Leadership ensured that the team had adequate representation including two floor nurses, a pharmacist, an IT representative, a surgeon, the physician champion, nursing director and a quality consultant. Dr. Goldsmith would report and work directly with CDS Committee Chair Jones and the rest of the CDS Team to develop the tools recommended by the QI Team.

They began by evaluating the current state of VTE prophylaxis utilization: the hospital had open admitting and considered itself ahead of the game with a fully functional EHR and CPOE in place for three years. The QI Team quickly realized that the VTE-related death was not an isolated event. While difficult to monitor, Grandview floor nurses often reported patients not being placed on VTE prophylaxis. The surgeon on the QI Team reported not having any order sets or guidelines to help prompt him to remember to start VTE prophylaxis, and he was unaware as to how well his colleagues were doing in their prophylaxis efforts. He knew some doctors had added this to post-op orders, but there was no standardization. No one seemed to recognize the significant gap between the hospital’s current approach to VTE prophylaxis and best practices.

At their first joint meeting, the QI Team and CDS Committee identified the committees with which they needed to interact in order to improve care processes and workflows. They noted that VTE prophylaxis is a part of national quality organization recommendations and aligned with hospital efforts to reduce non-reimbursed complications—so they would need to collaborate with all hospital groups focusing on those issues. Although an initial focus for the joint efforts was VTE prophylaxis, the CDS Committee participants recognized that that it would be important to use this particular improvement effort as a scalable model for approaching other PI projects. For example, they needed to determine who would take ownership of defining patient selection criteria, intervention standards of care and related protocols for best practice VTE prophylaxis—and would need to likewise achieve local consensus on best patient care practices as a central component of other CDS projects as well.

Understand and cultivate key CDS building blocks including your deployed information technology, documentation of clinical workflows and capacity to measure intervention effects.

Chair Jones and other CDS Committee members were aware that some EHR systems and CDS vendors had pre-configured CDS interventions that addressed VTE prophylaxis through risk assessment forms, order sets for appropriate therapy, and other tools. However, they didn’t have any readily available documentation or shared sense of the info...