![]()

![]()

Books about ancient Egypt take for granted that the ancient Egyptians were already, in essence, a nation. It is natural to say that the Egyptians believed in such and such a thing and acted in a certain way. Modern historians, however, might not altogether agree and ask: ‘Are you sure? Are you not being naive?’ For they tend to see the concept of nationhood and national consciousness as having begun in western Europe in the eighteenth century, and as having been somehow linked to the decline in the power of religion. Nationhood is, from this point of view, to be contrasted with large cultural systems that preceded it, in particular the ‘religious community’ and the ‘dynastic realm’. Mediaeval Europe supplies the pre-modern norm. Christianity and the Latin language, and the transfers of rulership of huge swathes of territory through dynastic marriages and conquests, created loyalties and enmities that transcended boundaries of shared inheritance and common language. Henry II, King of England (and Wales), spoke French as his first language and owned and ruled almost the same amount of territory in France. This seems the antithesis of circumstances in which nationhood exists. Another example, very relevant to Egypt, is the Ottoman Empire which, in its heyday, extended from Budapest to Baghdad, from Cairo to the Caspian Sea and held within its embrace many diverse societies, separated by language and local history. What unified them was Islam, the Arabic language (and to a lesser extent the Ottoman language of state business), and loyalty to the Sultan and to his representatives. Only in the wake of its collapse came the assertion of local identities which either transformed themselves into nations (as with Greece and Egypt, and the Ottoman heartland of Turkey) or have struggled to do so through more than a century of communal violence, particularly in the Balkans and more recently in Syria and Iraq.

Collective identity is an ancient, deeply felt, and sometimes murky attribute of humanity. It begins on the very local scale, and much of human history is concerned with its evolution although, as pointed out in the Introduction, the move from hunter-gatherer groups to societies in which dominance hierarchy was the rule is thought to have begun relatively late and has proceeded with different degrees of intensity and on different scales ever since. Nor is the nation-state necessarily the final grouping. Beyond it lies the potential of transnational or transregional groupings which have been achieved in the past (often in the form of empires). India, the USA and China are examples of very large territories that have managed to become ‘natural’ units. The voluntary union of European states aspires to something like this status (and also illustrates the point that moves towards harmony engender perverse opposites, in the shape of national political movements dedicated to weakening it). Furthermore in the 1960s the short-lived political unions linking Egypt with Syria, Iraq and Libya (to create a United Arab Republic) had the same aim. We still live in a politically transitional time.

The imagined community

Central to the concept of the nation is

People live in a world of their imagination whilst simultaneously negotiating daily realities. By this definition of the nation ancient Egypt passes the test reasonably well. The ancient Egyptians, speaking and writing a common language, occupying a territory with a well-catalogued geography centred on the Nile valley and subscribing to a distinctive culture, imagined themselves as a single community. Central to that imagined community – and it is here that we meet the principal difference from modern nationhood – is that it was presided over by a line of divine kings, Pharaohs. Yet we should not emphasize this difference too much, for Egypt had an existence separate from Pharaoh, and rulers were heavily obligated to maintain the integrity of ‘Egypt’. They served it and were ‘the herdsmen of mankind’, the latter term meaning, of course, Egyptians (just one version of the conceit that anthropologists have found to be widely spread in the world of tribal societies; that is, ‘we’ alone are synonymous with true humanity). Moreover, kings owed their own unique position to the continuing existence of the country called Egypt that they ruled and of its wealth of traditions. The line of the Pharaohs and all the marks of their legitimacy to rule continued through the first millennium BC, even though by then the holders of the office were mostly of foreign origin, from Libya, the Sudan, Assyria, Persia, Greece and Rome.

The imagined community of the nation contrasts itself with the world outside. ‘We’ are special, ‘they’ are inferior and do strange things. The sense of community in the modern world is developed and maintained by diverse means, including the reading of newspapers the editorial policies of which promote national identity, most strongly by disparaging foreign peoples and nations. The Egyptians took pleasure in this kind of thinking, too. We meet it well developed in a piece of ancient Egyptian fiction, the Story of Sinuhe, a tale of temporary exile in Palestine endured by a courtier of the early Twelfth Dynasty who feels the need to flee as a result of accidental implication in a conspiracy to thwart the royal succession. The assumed readership is the Egyptian literate class and, although seemingly composed around 1950 BC, the story was still being copied as a school exercise seven centuries later.2

To leave his country, Sinuhe has to creep by night past the frontier fortress named ‘The Walls of the Prince’, which, he states, ‘was made to repel the Asiatic and to crush the Sand-farers’ (i.e. the Bedouin). Close to death in the desert he is rescued by one of these very same people, a passing cattle nomad who offers hospitality. In his subsequent exile in Palestine he exchanges his persona as an Egyptian courtier clad in fine linen for that of the head of a tribe, and is eventually forced to adopt the role most antithetical to that of the Egyptian scribal elite, the warrior who becomes the hero of personal combat. Despite his local success, there is no mistaking the sense of longing for the distant homeland, which is both a place and a community, namely Egypt. ‘Come back to Egypt!’ are the very words of the king’s subsequent personal advice. At the heart of this longing is the thought that Egypt is the only proper place in which an Egyptian can be buried. Much emphasis is placed on this. To ease the pain of exile, the Palestinian ruler who befriends Sinuhe tellingly remarks on the linguistic aspect of community: ‘You will be happy with me; you will hear the language of Egypt’, evidently from other Egyptians who, he states, were already with him. Eventually, pardoned by a benign king, Sinuhe returns to Egypt, to an enthusiastic welcome and to a self-indulgent shedding of the taint of foreignness: ‘Years were removed from my body. I was shaved; my hair was combed. Thus was my squalor returned to the foreign land, my dress to the Sand-farers. I was clothed in fine linen; I was anointed with fine oil. I slept on a bed.’ And a magnificent tomb with a gilded statue in its chapel was made for him at the king’s expense.

It is all there: geographical frontiers, language, dress, bodily cleanliness, even sleeping on proper beds; and were not Egyptians lucky to be ruled by so powerful yet benign and generous a king? By these marks Egypt was defined as a nation, which could still be imagined in these terms centuries later as the text was copied and read. It should be noted, none the less, that Sinuhe’s picture of the ‘Asiatics’ is essentially a kindly one. They might be uncouth, but they behave with honour and kindness. They do not commit acts of savagery. Sinuhe inhabits a world, or at least a literary dimension, of civilized manners.

The term which Sinuhe uses throughout for ‘Egypt’ (Kmt) means literally the ‘black land’. In other sources it is often contrasted with the ‘red land’, as in the reference to a mythical partitioning between the gods Horus and Seth: ‘The whole of the Black Land is given to Horus, and all of the Red Land to Seth.’3 It is thus reasonable to understand the pairing of the two terms as a contrast in basic soil colour: the black soil of the alluvial plain of the Nile and the sands and rocks of the desert which Egyptians included within a colour term which we conventionally translate as ‘red’ but which really embraced a wider palette. As for themselves, the Egyptians often used a term which is sometimes to be appropriately translated ‘the people’ (as in ‘people of Egypt’ in Sinuhe) or more broadly as ‘mankind’. It made them the centre of the universe; they were the norm. In a myth recorded in several royal tombs of the New Kingdom ‘mankind’ rebels against the ageing sun god Ra, who is called ‘the King of Upper and Lower Egypt’.4 From his wrath they flee into the desert and are there pursued to destruction by an avenging goddess whose lust for blood is assuaged by red-pigmented beer being poured over the fields as if it were an inundation of the River Nile. The imagined location is clearly Egypt and ‘mankind’ are the Egyptian people. As the norm of humanity Egyptians as ‘mankind’ were to be contrasted with specific groups who lived in the other parts of the world known to them. At the furthest limits were the inhabitants of Punt (modern Eritrea) who were said to ‘know nothing of mankind’.5

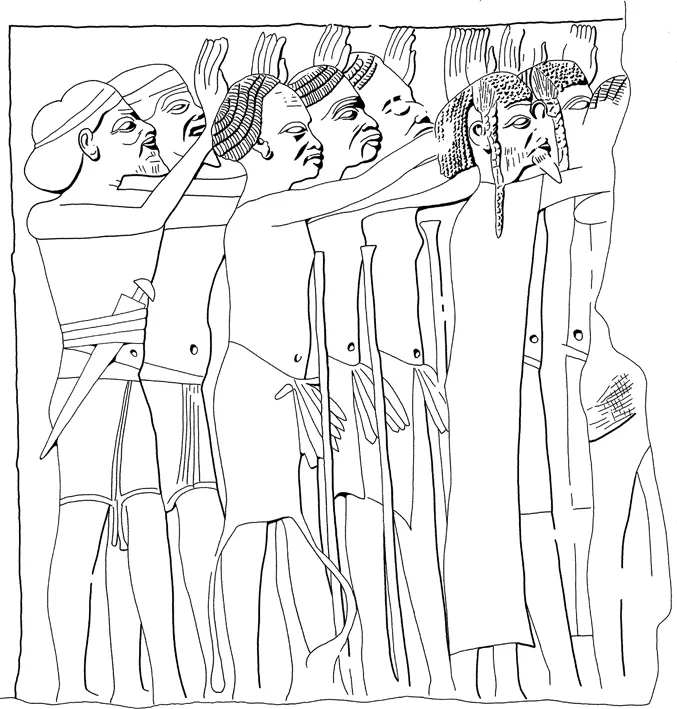

Egyptians delighted in type-casting their subdivisions of foreigners, and did so with deft stylization (Figure 1.1). By means of clear conventions of classification, using facial shape, skin colour and dress, they identified particular groups: Nubians, Asiatics, Libyans, peoples from the Aegean, and from the eastern Sudanese/Eritrean land of Punt. These stereotypes came to life again in the nineteenth century AD as western scholars began to record the ancient monuments and thus to explore the ancient Egyptians’ world through their eyes. It produced, for a while, a mood of over-confidence, in which the ancient Egyptians’ portrayals of foreigners were regarded as almost photographic representations of ‘racial types’, a subject then high on anthropologists’ research agenda. ‘The same form of head is characteristic of the Armenian to-day, though with a larger nose’ was one such early twentieth-century comment on a relief at the temple of Abu Simbel.6 We have become more cautious with the evidence since then.

To complement racial stereotyping the Egyptians from time to time expressed demeaning opinions. ‘The Asiatic is a crocodile on his bank. He snatches from a lonely road. He cannot seize from a populous town’ is part of the advice of one king to his successor (Merikare, c. 2050 BC).7

announces King Senusret III on his southern boundary stela at Semna, in Nubia (c. 1870 BC).8 Libyans who, in the time of Rameses III, threatened Egypt (c. 1170 BC), are made to admit their folly after their defeat:

More often, the foreigner, when in the position of a foe, is simply designated by an adjective which seems most appropriately translated as ‘vile’.

From pictures and words of this kind – and the examples are very numerous – we might paint a picture of the ancient Egyptians as racially exclusive. By the first millennium BC outsiders were already claiming this to be so. The Greek travel-writer and historian Herodotus, observing that ‘no Egyptian, man or woman, will kiss a Greek, or use a Greek knife, cooking-spit, or cauldron, or even eat the flesh of a bull known to be clean, if it has been cut with a Greek knife’, put this down to Egyptian distaste of any people who were prepared to sacrifice cows, sacred to the goddess Isis.10 In a similar tone the Jewish historians who put together the Old Testament around this time or even later, in composing their parable-like tale of Egypt and Israel, explained the seating arrangements for a meal at Joseph’s house by saying: ‘for the Egyptians cannot eat with the Hebrews, for that is detestable to the Egyptians’.11 To what extent these are themselves caricatures made to pander to the intended home audiences is now hard to tell. For by contrast, sources from within Egypt point to a much greater variety of Egyptian response to foreigners in day-to-day affairs.

Building frontiers

The Egyptians attempted, by means of border controls at the corners of the delta and across the Nile in the south, to check the immigration of the Asiatics, Libyans and Nubians. The ‘Walls of the Prince’ which Sinuhe had to avoid was one such control. It has yet to be identified with an archaeological site, but its probable successor in the New Kingdom, by then named Tjaru...