![]()

1

THE ART OF SURVIVAL

‘The past resembles the future more than one drop of water resembles another.’

– IBN KHALDUN, MUQADDIMAH (1377)

In June 2018 the Mekkah newspaper reported that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was planning to dig a canal that would separate the Qatar peninsula from the mainland, turning it into an island. Announced in the midst of a diplomatic feud between the two countries, the project envisaged a 48-kilometre (30 mi.) waterway running from Salwa in the west and Khor al-Udaid in the east, and included a tourist resort, nuclear waste dump and military base. The Saudi government made no official comment on the story, but a number of Saudis celebrated the news, with an adviser to the crown prince declaring that they were ‘changing the geography of the world’. Unsurprisingly, Qataris were outraged and comparisons were made with the great battles of the Prophet Muhammad.1

There was a quiet irony in this, however, for Qatar might well have been an island in the dim and distant past, cut off from the mainland by a great river that flowed out of the Arabian interior. It is hard to imagine that a landscape which is so dry and devoid of life was once green and teeming with it, but only 6,000 years ago this was a more temperate clime; hunters gathered around watering places, leaving behind flint arrowheads and stone tools for modern archaeologists to find. Then the climate changed and Qatar became the place we recognize today: the sea retreated and the great river disappeared. Now there are no rivers in Qatar, or in Arabia as a whole, only the dried-up river beds called wadis that swell into raging torrents when the rain pelts down.

‘Qatar is the land God forgot,’ Arabs would say, alluding to the desolate nature of the 10,400-square-kilometre (4,000 sq. mi.) peninsula, which is a largely stone and sand desert with precious few wells scattered about – mainly in the north – and hardly any trees in sight. Inland settlements were the exception, and the desert remained the preserve of nomads, the early bedouins, who migrated across their diyar, following the rains. The sea was Qatar’s saving grace, offering rich pickings of fish and pearls, and the settlers who came here created a ragged line of small camps and fishing settlements strung out along the shore.2

The sea in question is the Arabian Gulf, that body of water that surrounds Qatar on three sides. More like a lake than a sea, its outlet narrows to a width of 47 kilometres (29 mi.) at the Strait of Hormuz. The Gulf brought more than trading opportunities, however, for it is relatively shallow on the Arabian side, allowing a profusion of oyster beds that sustained a thriving pearl trade. A wealth of marine life inhabits its waters, providing a vital food source for the communities that made a living from its shores. But there is also an abundance of coastal shoals and reefs, making navigation difficult and dangerous for all but the most experienced nakhudha.

The waters of the Gulf endow the coast with great humidity, which lessens as you venture inland. In the summer the northwesterly wind known as the shamal can prevail, and in the late summer and autumn the kaus or humid sharji winds can blow from the southeast, creating sandstorms that smother the landscape. During winter and spring, the climate is cool and mild, although Qatar can also experience sudden, violent storms. Rain brings contrast and relief to the desert: the freshness of the dawn, the clarity of the sky and a feeling that life has started all over again.

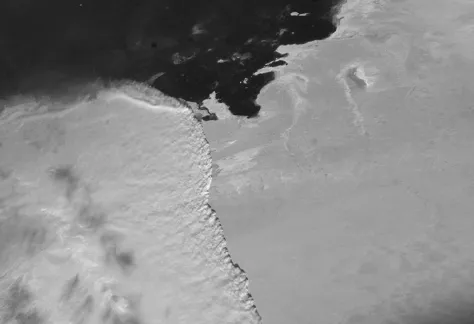

A massive sandstorm sweeps over Qatar as it heads towards the border with Saudi Arabia on 15 February 2004. This photograph was taken from the International Space Station.

The power of the elements is dramatized in the folk tales of the Gulf. There is a story about the ‘She Donkey, Lady of Midday’, a half-woman, half-donkey who goes out and eats children when the sun is high – a cautionary tale used to discourage youngsters from going out in the noonday heat. Another tale, ‘Bu Draeyah’, tells of a sea creature that lures sailors into the water’s depths and kills them. But the fears of those who lived in the pearling towns were real enough. Less than a century ago, the seafarers of Bida’a, Wakrah and Al Khor – to name but a few – set sail for the pearl beds of the Gulf, their slanting masts disappearing into the deceptive calm of an early summer morning while their loved ones were left behind to pray for their safe return. Pearling was a dangerous business, and crews would spend months away from their homes. The year 1925, when an exceptionally violent autumn storm saw as many as 5,000 lives lost at sea, was remembered as the ‘Year of Drowning’.

Qatar remained an enigma to the West, even when there were extensive contacts between the Gulf and the Mediterranean world. Indeed, early European cartographers barely recognized the place. One seventeenth-century map, probably based on travellers’ tales, mentions ‘Catura’ on the Arabian coast, but there is no sign of a jutting peninsula, only a flattened coastline with a few towns dotted along it. For many years, ‘Qatar’ referred to a town on the eastern side rather than the peninsula as a whole. There were several different spellings, such as ‘Katr’, ‘Kattar’ and ‘Guttur’ until the name ‘Qatar’ stuck in the twentieth century. There is still confusion among foreigners about how to pronounce it – apparently ‘Gutter’ is the preferred version – and trying to explain the origin of the name is an interesting but ultimately futile exercise, involving abstruse discussions about rainfall, smelted copper, burnt incense, camels, red cloth and so on.

As you might expect, however, modern cartographers have remedied the anomalies on the map and, when sandstorms are not obscuring the terrain, satellite photographs confirm Qatar’s proud existence. Although in recent times the peninsula has disappeared – as happened recently when a map displayed in the Louvre Museum in Abu Dhabi showed a blank space where Qatar should have been – it is impossible to miss, for it sticks like a defiant thumb into the seemingly placid waters of the Gulf. Nevertheless, it is a small country about the size of Yorkshire in England, or the state of Connecticut in the northern United States.

The early people of this land made their living from pearling and fishing, and established their first connections with the outside world through maritime trade. At Ras Abrouq, pottery sherds from the Ubaid period (7500 BCE–6000 BCE) have been discovered, indicating a link with Mesopotamia. It is also known that a scarlet dye made from local molluscs around Al Khor Island was exported to Babylon; this was later used for the Qatari flag, its colour darkened to maroon by exposure to the sun. Other discoveries link the peninsula to the Dilmun civilization, which existed on Bahrain between about 2450 and 700 BCE and was the centre of a trading network stretching from Mesopotamia to Magan (Oman).

Islam arrived in 628 CE when the Prophet Muhammad sent his envoy to Munzir bin Sawa, who was the Sassanid governor of eastern Arabia. He accepted Islam, with the result that the Arab tribes also converted, although it is likely that this happened over decades rather than overnight. The Christian name for the region was ‘Beth Qatraye’, and there is evidence of a Christian presence on the peninsula that eventually died out towards the end of the seventh century CE as followers turned to Islam or emigrated elsewhere.

Arab geographers used to refer to the Qatar Peninsula as part of ‘Greater Bahrain’, which encompassed eastern Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the island of Bahrain, but that term did not impart any lasting sense of government, state or administration. By the thirteenth century ‘Greater Bahrain’ had fallen into disuse, ‘Bahrain’ referred to the Bahrain archipelago and Qatar was a few coastal settlements under the leadership of local chiefs. Among the early settlements was Murwab on the northwest shore which, during the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258 CE), had 250 houses, a fort and two mosques; the fort is the oldest known in Qatar. In the thirteenth century, the peninsula was renowned for its horses and camels, and – hence one theory about the origin of its name – the production of red woollen cloaks, which were exported abroad.

The arrival of the Portuguese in the Gulf and their conquest of Bahrain in 1521 marked the start of a lengthy power struggle in the region that continued into the nineteenth century. The Qatari tribes were often divided and prone to outside influences, and their towns and villages vulnerable to attack. The peninsula was used as a base for the so-called ‘pirates’ who operated from its shallow creeks and waters, its towns were periodically bombarded by British gunboats, assaulted by Persian, Bahraini and Omani navies, and occupied by the armies of Nejd.

The historical documents can only tell us so much: there are possible mentions of Zubarah, Bida’a, Fuwairat and Al Khor in the 1681 records of the Carmelite Convent, and Furayha is mentioned in an Ottoman document of 1701. But, as the archaeological sites have been painstakingly excavated, a more dramatic picture emerges, for it is now apparent that the coastal settlements were repeatedly occupied and abandoned over the years, a cycle that was determined by the boom and bust years of the pearl trade, the vicissitudes of tribal conflict and foreign intervention. All in all, it seems that Qatar was quite an eventful place to be.3

OUR STORY REALLY begins in Nejd, in the heart of Arabia. The name denotes high land or a plateau and describes a desert running between Hail in the north and the Rub al-Khali in the south. It was an unpromising place for trade, since it was largely deserted and far from the coastal trading routes of the Gulf and Red Sea. However, it did have a large number of oases, which acted as a magnet for human settlement; from one of these places the ruling Al Thani family of Qatar derived.

Their forebears belonged to the Ma’adhid, part of the Bani Tamim tribal confederation which made a living by growing dates and cereals in the string of oases around Washm, an area about 130 kilometres (80 mi.) to the northwest of Riyadh. From here a market system and trading networks developed, in which the Bani Tamim played a prominent role. The seven settlements of Washm kept to their pastoral occupations, were relatively self-contained and showed no immediate enthusiasm for the Islamic radicalism that swept across Arabia from the mid-eighteenth century.4

The Ma’adhid lived in one of the larger settlements, Ushayqir. Renowned as a centre of learning, Ushayqir was on the western side of Washm and vulnerable to attacks from the sharifs of Mecca, as well as being disrupted by local rivalries. It seems that, for whatever reason – drought, famine or conflict – the Ma’adhid decided to leave Ushayqir around 1700 CE and settle in the Yabrin Oasis, about 320 kilometres (200 mi.) to the southwest of modern-day Doha. And so they left Washm before the rise of Wahhabism, a radical Islamic movement which sprang up in Arabia during the 1740s.

The Wahhabis are often described as a military force in their own right, but in fact they were the religious wing of an army led by Muhammad bin Saud, the sheikh of Dariyah, a small town in Nejd and seat of the Al Saud dynasty. The Wahhabi movement was named after its founder, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, himself a member of the Bani Tamim. He was a Hanbali preacher who preached a religious doctrine of going back to the basics, stripping religion of all its baubles and demanding that nothing should come between man and God. The combination of military prowess and religious fervour made the Al Saud–Wahhabi alliance a formidable one, and it was with a certain dread that their enemies spoke of the ‘Wahhabi’ amir.

‘I am the book, you are the sword’ is a saying that sums up Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab’s pact with the Al Saud when they joined forces in 1744, which was reinforced by the Al Saud leader being an imam of the Muslim community. From Dariyah, Wahhabi forces made conquests and tribal alliances across Arabia, extending their domain from shore to shore to establish what historians have called the First Saudi State. Their use of violence was based on the Islamic concept of jihad: that those who did not devote themselves exclusively to God were idolaters and therefore should die, but only if they had received his message, understood and then rejected it.5

In practice, how did this work? We might picture a single envoy riding out of the desert with a letter to a sheikh demanding that his tribe submit. If the tribe conceded, they would pay zakat, a religious tax that was collected at regular intervals by Wahhabi tax collectors. If a tribe resisted, a ferocious and ruthless attack would follow, and the custom of jihad, or holy war, might be invoked. But that was one of several possible scenarios, for there were many ways in which contact might be made, whether through visiting scholars, returning traders or a ragged army rising out of the dust.6

A tribal sheikh had a number of strategies he could use to avoid outright warfare. For example, he might negotiate an agreement under the aegis of a neutral sheikh acting as mediator, or he might assess his own military position and, if it was weak, pay zakat to stave off the threat, or his merchants might press him to settle matters in the interests of trade. Alliances were important, and the practice of dakhala – seeking the protection of a more powerful sheikh – was the most effective device of all. However, although such tactics were tried and tested in a traditional setting where both sides recognized their worth, they were not always successful against the Wahhabi threat.7

A restored mud-brick dwelling at Ushayqir in the Nejd region of Saudi Arabia, where Qatar’s ruling family originated.

And so reactions to the Wahhabi advance were mixed: in Washm, for example, settlements such as Tharmada and Ushayqir resisted, others like Qara’in were equivocal, while Shaqra joined the Wahhabi cause. Those in opposition suffered economic attrition and sporadic military interventions until the whole of Washm had capitulated by the end of 1767. The process happened over a long period, a matter of decades rather than a single campaign, since this was no sudden conversion.

By then the Ma’adhid and the Al Thani forebears were long since gone, and had moved on from the Yabrin Oasis to settle at Ruwais and Zubarah on the northern coast of the Qatar peninsula.

IN THESE YEARS, we see the leading dynasties of the region starting to emerge: the Al Saud of Nejd, the Al Sabah of Kuwait and the Al Khalifa of Bahrain – the Al Thani of Qatar were relative latecomers to the feast. The ancestors of the Al Khalifa family came from the Al Aflaj region, 320 kilometres (200 mi.) southwest of Riyadh in centra...