![]()

Three

Edo as Sacred Space

Nihon-bashi was Edo’s monumental centre, but another part of the city, constructed analogously, also gathered structures that articulated a collective meaning. This site was less political than religious and had been constructed to sacralize the shogunate, rather than to illustrate its power. This iconic nexus was not in the centre but in the northeast, the geomantically sensitive kimon, the ‘gate of demons’. As explained in Chapter One, this was the sensitive direction by which ki, or spiritual forces, entered the city. Edo was protected by its castle and its numerous moats and was rendered a site of benevolent rule by its central bridge, but in the northeast quarter it was also protected by Buddhist temples.

Japanese geomancy, or the ‘way of yin and yang’ (onmyō-dō), stipulated that the northeast should be guarded. The shoguns ensured this by positioning the residences of their most loyal hereditary warriors, the fudai daimyo, there. This protection had begun earlier in a religious sacralization of the vector, which is the subject of this chapter.

Placing temples in the northeast was standard practice. Japan’s first complete capital, Heijō-kyō (Nara), had a colossal compound in that direction. It was fulsomely named the Temple of the Protection of the State by the Gold-Wondrous Kings and the Four Heavenly Kings (Kongō myōō shitennō gokoku-ji). Being a mouthful, the place was popularly known (and still is) as the Great Eastern Temple (Tōdai-ji). Properly it should be the Great Northeastern Temple, since its purpose was to project the kimon. A whole ‘outer capital’ grew up around the temple as an excrescence on the city grid. Heian-kyō (Kyoto), the capital for much of Japanese history, was constructed in the knowledge that Heijō-kyō had been overwhelmed by the power of its clergy. Its northeast was also protected by a temple, but one located far out of town. Not merely some 20 kilometres outside the city, it was also on top of a mountain, Mount Hiei, 850 metres high. The temple also had a fulsome name, but of a different kind. It subordinated Buddhist to civil power. Most temples have names invoking religious concepts, but this one was named after the era of its foundation, as the Enryaku-ji, or Temple of the Enryaku (‘extending calendar’) era, which spanned the years 782–806. Its precincts on Mount Hiei were very lavish and entirely crucial to the running of the state, but Enryaku-ji’s name defined it as subordinate under the secular sphere.

Warrior cities of the medieval and civil war periods tended to have temples in the northeast, and it was to be expected that Edo would have one. When Tokugawa Ieyasu established his base in Edo in 1590, it so happened that there already was a temple more or less to the northeast of the castle, and long pre-dating it. The history of the institution is lost, but it was certainly old. Places of local worship had existed all across the archipelago for centuries, and this one, in the village of Asakusa, a short distance up the Great River from Edo, was enlisted by the Tokugawa.1 It was known as the Asakusadera (-dera is appended to Japanese-language temple names, as -ji is to the more numerous Chinese-derived ones). When Ieyasu moved to the region the monks of the Asakusa-dera saw a chance to aggrandize their cloisters. It was by lucky chance – or was it providence? – that it sat in the kimon of Ieyasu’s castle. Ieyasu naturally visited it, and the monks offered services for his cause. They pointed out to him that the temple’s principal icon was wonder-working, and since Ieyasu always won his battles, its power was suitably confirmed. The Asakusa icon laid the ground for the creation of his shogunate.

The icon did not represent a Buddha but a lesser figure, a bodhisattva or ‘Enlightenment being’ – that is, one who at the point of Enlightenment deferred it, in order to remain immanent in this world and help others on the way to wisdom. Bodhisattvas are many, but that enshrined at Asakusa represented Kannon (C: Guanyin). It is he who will convey the deceased to rebirth in the Pure Land (jōdo). This icon, the monks asserted, was an acheiropoieton (as such things were known in Europe), a miraculous image not made by human hand. Legend had it that two fishers had found the sculpture in their nets and, terrified, had thrown it back, moving their boat elsewhere. When they fished again, the same object was dragged up. This happened repeatedly, until they realized the image wanted to be taken to land, and so they placed it on the bank and erected a little shrine. Knowing nothing of Buddhist precepts, the villagers called this the Asakusa-dera, from the location. They could however recognize it as Kannon, whose iconographical marker is a crown with a buddha image on it. The shrine came to be known as the Asakusa Kannon. Thereafter, the two fishers always had wonderful catches, and the fame of the icon spread. Word came to the attention of a wandering monk, who conducted the first formal service in front of the Kannon. Then he went blind. The image appeared to him in a dream, telling him it did not wish to be seen, so the next morning it was sealed in a shrine, and the monk’s eyesight returned. The Asakusa Kannon became a ‘secret Buddha’ (hibutsu), of which there are several in Japan, only rarely revealed at moments of special sanctity. It may have been this monk who upgraded the temple name to something more formal. As well as Asakusa-dera, it might be called the Sensō-ji. However, this is just the characters for Asakusa pronounced in the Chinese way, Sensō, with -dera accordingly changed to -ji.

As a northeast protector temple, the Asakusa-dera, or Sensō-ji, had some deficiencies. It had not been built to project the castle as it existed long before, so it was not well aligned, more east than northeast. Moreover, it was on the riverbank, whereas protective temples should be on an eminence. The mountaintop Enryaku-ji was extreme, but even Heijō-kyō’s Great Eastern Temple was on a hill. Also, while Kannon had a cultic following as the conveyor of the dead to blissful rebirth, he is not a buddha as is required at a protector temple. These discrepancies were tolerated at first, but as Edo grew, they became problematic.

With a requirement for something that fitted the bill more precisely, a new temple was founded in 1625. Ieyasu was dead, and this was the work of his grandson Iemitsu, installed in 1623 as the third shogun when his father, Hidetada, went into retirement. The Tokugawa regarded it as worthwhile to take the considerable step of protecting their city and sacralizing their regime with an entire new temple complex. The timing also meant that the temple would be ready for the millennial anniversary of the finding of the miraculous Kannon by the fishers, which the monks dated in accordance with 645 – the myth is just as likely to have been given a date retrospectively to match. The new temple would be properly in the northeast, on a hill, and would enshrine a buddha.

Work was put under the care of a senior monk, Tenkai, who had studied at the Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei. He had been close to Ieyasu, who had awarded him a temple at Kawagoe, a strategic town close to Edo; the precinct was named the Kita-in (‘cloister of much happiness’; -in denotes a small temple). Though not initially large, the Kita-in was given an impressive additional name. All temples have a ‘mountain name’ as well as their normal designation, and the Kita-in was proclaimed Tōei-zan (‘Mount Hiei of the East’). This brought the capital’s protector temple and its long, pious traditions into Ieyasu’s orbit, albeit outside Edo proper.

39 Konpon chūdō, Enryaku-ji, Mount Hiei, as rebuilt 1660. The principal hall of the capital’s great northeastern protector temple, destroyed by Hideyoshi but rebuilt under the Tokugawa.

Tenkai was fully aware that Edo had a hilly area exactly northeast of its castle. It had been allocated to fudai loyalists of the Ueno daimyo family, but they agreed to relinquish it. The place had become known as Ueno, which fitted, since it literally means ‘upper plain’. The name selected for the new, projected temple is telling. It was to be Kan’ei-ji, where Kan’ei (‘long lenience’) was the era then under way (1624–43), promulgated upon Iemitsu’s accession as shogun. This matched the Enryaku-ji, also named after the era of its foundation, eight hundred years before. Hardly any Japanese temples have era names, so the Kan’ei-ji was very clearly copied after the model of the protector of the capital.

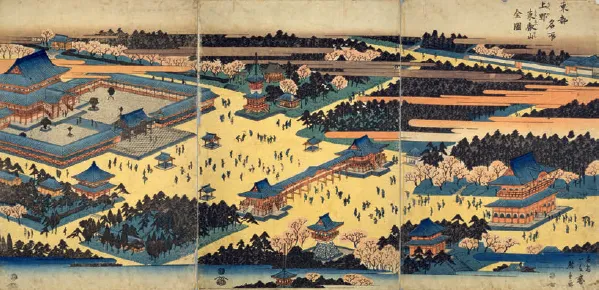

40 Utagawa Hiroshige, ‘Complete View of Tōeizan Temple in Ueno’, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital, c. 1832–4, multicoloured woodblock print. The Edo temple copied the name and general appearance of the protector hall outside the capital.

Parallels were further reinforced. Tenkai’s colleagues at the Enryaku-ji sent a magnificent buddha, very ancient, to be the principal icon. It was said to have been made by the Enryaku-ji’s founding abbot, Saichō. This eminent cleric had studied in Tang-dynasty China and won great renown. He is not known to have been a sculptor, so the attribution is not accepted today, though association with his hand would have justified special veneration at the time. The specific figure was the Medicine Buddha (J: Yakushi nyōrai), which was also the Enryaku-ji’s own principal icon, so the Kan’ei-ji matched here too, with Edo protected by the same buddha (there are many) as the capital. A huge central hall was erected to install the piece, called the Ruri-den (‘hall of lapis lazuli’), from the Medicine Buddha’s associated colour, blue. This hall had a second name, Konpon-chūdō (‘hall of the central fundament’), which was also the name of the Enryaku-ji icon’s sanctuary. Or, rather, it had been. The Enryaku-ji Konpon-chūdō was no longer there. It had been lost in the civil wars, its icon now temporarily housed elsewhere. As part of the sacralization of Edo, the shogunate borrowed, but also subsumed, the capital’s aura. Only once work on the Kan’ei-ji had begun did Iemitsu pay for the rebuilding of the Enryaku-ji’s originating structure. Both halls were so vast that they took many years to build. The Enryaku-ji’s Konpon-chūdō required eight years, while the Kan’ei-ji’s was not completed until 1697 (illus. 42 and 43).2 For its ‘mountain name’ the Kan’ei-ji was accorded Tōei-zan (‘Mount Hiei of the East’), with the title therefore removed from the Kita-in (it was suitably compensated). Tenkai was nominated to be first abbot. The shogunate now had a protector precinct perfectly in accordance with requirements, both mirroring and supplanting the protector temple in the capital.

The Kan’ei-ji was reserved for government use. The shogunate endowed it with an income of 5,600 koku. This largesse compared with the older Asakusa Kannon, on an endowment of just 500 koku. The latter was now turned over to city use. As it needed commercial activities to survive financially, the Asakusa precinct became almost like a fairground, with shops even inside the temple grounds. Most commoner families had, or would acquire, graves here, ensuring crowds of visitors, and when the Kannon image was revealed, huge throngs came. This atmosphere contrasted with the Kan’ei-ji, where the halls were quiet and sober. Between them, the temples provided for all Edo’s social classes, and together t...