- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Whether in a court room or a dressing room, wigs come in many forms and represent many things: from power, to sexuality, to parody, to health, to self-identity, to disguise. Wigs are present at parties and in chemotherapy rooms, in pop music and contemporary art. In this witty and eloquent book, Luigi Amara reflects on the curious history of the wig and along the way takes a sideways look at Western civilization. Amara illuminates how the wig has starred throughout history, from ancient Egypt to the court of Louis XIV, and from British courtrooms to drag shows today. Containing many striking and unusual images, The Wig will appeal to all those interested in the history of fashion—as well as philosophy, art, culture, and aesthetics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Wig by Luigi Amara, Christina MacSweeney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Rage Called Wig

As often happens with great revolutions in fashion, the empire of the wig was established more by chance than design or ingenuity, and if half the populations of France and England in a particular period began the day by donning a head of false hair, this is in great part due to the fact that vanity, chance and even the anomalies of the body are hidden mechanisms in the motor of history. ‘Many surprising fashions in dress have arisen from the fact that a famous man or woman tried to conceal some infirmity,’ wrote Jean Cocteau, in a statement that could be seen as an apposite description of the capillary excesses of the seventeenth century, when, for the first time since ancient Egypt, men were infected with the passion for sham hair and women flaunted coiffures so high and prolific that stuffed birds nested in them.

Although Louis XIII’S premature baldness stands out as the root cause of a renaissance of the wig that extended over almost two centuries – until its symbolic ending in the French Revolution – already, in 1620, Abbé de la Rivière had been greeted with an ovation when he appeared in court with a resplendent model that reached to his waist. Travellers had previously mentioned the enthusiasm in Paris for an eccentricity named perruque, which was an audacious solution to the age-old problem of depopulated pates. But once the king began to sport an asymmetric variety – the left side was longer than the right – the wig spread like a plague of mystifications, first among the court and gradually as an emblem of the professional classes; in spite of the high production costs and their supposed link to migraines, vertigo, hives and apoplexy, very soon all and sundry – from servants to the clergy, and even children – were wearing perukes, and in certain spheres a refusal to do so was considered as stubborn and ridiculous as spurning trousers would be nowadays. The Royal House of France employed 48 master craftsmen to meet the needs of Versailles, and the nascent guild of barber-wigmakers – whose sharpened instruments were no longer used in operations of a surgical nature and which, a century later, would have over a thousand members in Paris alone – became so honourable that one of its most celebrated members, maître André, believed he had the right to correspond with Voltaire on equal terms.*

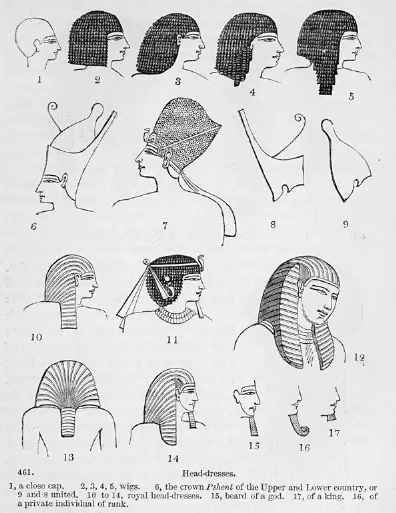

How was it that an improbable tangle of hair rose to the heights of being a byword for breeding and sophistication? What form of imitative process was at work for the wig to become a common necessity and not just the badge of the aristocracy? In the past, emperors and queens had used them without unleashing such a fever, and if the custom of borrowed hair had spread due to climatic conditions (by the time that Nefertiti’s pathological baldness obliged her to use hairpieces, Egyptians had for a long while been shaving their heads to combat the heat, thus assigning the wig a place in social life), or could be understood as a caste attribute or patrician insignia (in Rome, they were worn by certain empresses and such emperors as Nero, Caligula, Domitian and Otho), never before had the fashion become so widespread that it seemed the whole world was imitating the king.

While in other times the wig had a tyrannical presence, like a fiscal measure for converting the spontaneous fruit of the follicles into riches, in the seventeenth century the equation was modified to the extent that the wig, converted into an object of desire and fascination, was able to shrug off the vulgarity of a decree. According to Dr Akerlio, in the middle of the fourth century BC, Mausolus, the ruler of Caria, decided to replenish his impoverished treasury with a never-beforeseen endowment of wigs, only to then, when the moment was right, publish an edict making it obligatory for his subjects, regardless of age, gender or social position, to shave their heads. When the wigs appeared for sale, the whole population was forced by law to buy them at incredible prices and, moreover, thank their sovereign for his foresight. It is no surprise that Mausolus gave negative connotations to the word ‘satrap’, even if one of the Seven Wonders of the World was erected in his honour.

Despite such ploys, and while the wig still functioned as a symbol of noble pedigree, in the mid-seventeenth century people of all classes were flocking to adopt some form of hairpiece, and models were produced for the various trades and professions. In his Tableau de Paris, the utopian writer Sébastien Mercier notes a connection between the professions and the wig in which appear kitchen assistants, lawyers, professors, choirmasters, scribes and notaries, plus judges and wigmakers themselves.**

Much the same occurred in England, where the fashion swept through farmlands and was such a runaway success among the working classes that it was soon hard to find anyone with natural hair, unless – as was the case of Samuel Pepys – it was in the form of a periwig that, either from vanity or fear of pestilence, he ordered to be made from his own sacrificed mane.

If it had once belonged in the higher spheres of society, as a kitsch yet revered mark of distinction, by the beginning of the eighteenth century it was a ubiquitous consumer product around which outlandish commercial practices flourished, including the use of young women willing to give up their tresses in exchange for aprons and handkerchiefs (never, according to Villaret, for money), itinerant salesmen offering second-hand items, and even the creation of illegal workshops, which on the margins of establishments with royal approval, offered wigs that had belonged to victims of the guillotine or models made from horsehair or wool that could easily be confused with mops.

In spite of the fact that hair has been associated with power, and among the ancient Gauls its length was like an aura of honour and freedom that never completely faded in the collective imagination, the rapid spread of the wig (it would infest North America as early as 1660) could not only be put down to monetary aspirations or an arriviste quest for status. Conspicuous consumption, which, according to Thorstein Veblen, defines social status and tends to be emulated in a form of struggle for recognition and class privilege, made the wig a ravelled object of desire – especially in an era such as the Baroque, with its devotion to the god of appearance – perhaps to the extent of covering the Western hemisphere in a heavy cloud of hair.***

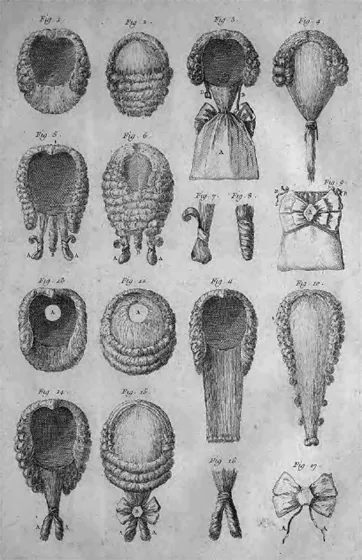

R. Bénard, after J. R. Lucotte, ‘ Wigs in a Wigmaker-barber Shop’, with figures 12 and 13 depicting tonsured models. Engraving in D. Diderot and J. le Rond d’Alembert, Recueil de planches, sur les sciences et les arts (1771).

There is clear evidence, such as that given by Pepys in his Diary, indicating that without a good wig, it was impossible to ascend the social ladder or attain a modicum of respectability (although he himself offers other, very good, reasons for their use, among them avoiding the need to wash: ‘I did try two or three borders and periwigs, meaning to wear one, and yet I have no stomach for it; but that the pains of keeping my hair clean is so great’); and while in those days a glance at the wig was enough to locate someone in the social hierarchy (those who had no choice but to display their bald eggheads must have lived in poverty), it is hard to believe that such a contagious fever was the result of a simple desire for ownership that we would nowadays describe as ‘aspirational’.

Like those sudden explosions of life that mark the fossil record, in just a few years wigmakers produced over a hundred different models, each with its own name; an exuberance, an authentic experimental orgy that makes one think that those shaggy fantasies touched deeper chords and unleashed more primitive impulses than those of ascent and rank. In his 1799 Éloge des perruques (In Praise of Wigs), which contains as many panegyrics as passages on history, Dr Akerlio describes a considerable number of models: from the ‘Caracalla’ to the ‘Venus’, the ‘Spanish’, the ‘Aspasia’ and, finally, the ‘Sartine’, which caught on in England and would become the emblem of the judiciary.

‘Crowns and headdresses of the Ancient Egyptians’, by J. Gardner Wilkinson, illustrated in A Popular Account of the Ancient Egyptians (1854). Figures 2–5 are conventional wigs; 10–14 denote royalty. The beard in figure 15 shows divinity.

The oppressive, fickle nature of fashion might explain why a man without financial means arranges his hair so that it looks as if he is wearing a wig. (The sense of confidence conferred by conformity of appearance, the satisfaction of pleasing the social guardian and its many eyes, may be greater, as Oscar Wilde insists, than the call of any religion.) But that simulacrum of a simulacrum, pitiful in its convoluted transparency, counterproductive as a mark of distinction, scarcely compares with those supernatural manes that became obligatory for no apparent reason, and were of a length and thickness that no human head could possibly have sustained: lush, leafy trees made from twenty mops of hair, stunning towers like moose antlers that attract attention and follow the logic of coquettish excess. The rage for wigs may well have had to do with the quest for social status or, as is sometimes insisted, hygiene (in those times, bathing was a sporadic practice and shaven heads prevented the invasion of undesirable fauna), but there is no doubt that the fascination of body enlargement was also involved, the mysterious alchemy between the face and its astonishing frame: the possession of a new, malleable excrescence with a semiotic appendage.

Envy, and the mimetic desire that sustains it – the wish to acquire and possess what others have, the urge to imitate the way others present themselves in public with their new appearance and their ability to squander money, through an authentic pyramid of desire understood as excess rather than lack – had much to do with this process, and Jean Baudrillard, in his For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, showing himself to be closer to Veblen than Marx, lays stress on the importance of consumer goods, in terms of not only their use or exchange value, but their value as a sign.

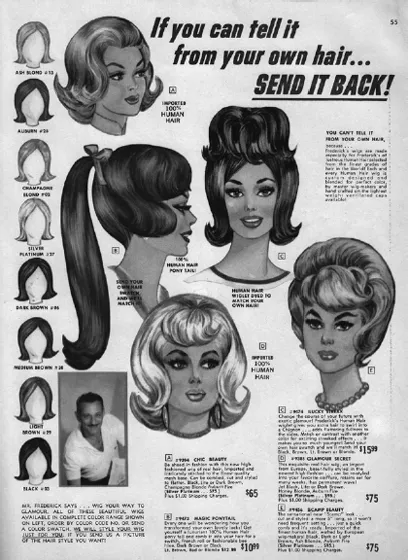

The wig as language, advertisement in a 1964 Frederick’s of Hollywood catalogue.

Just as with the wristwatch, perfume and other items of personal care, the wig was one of the sumptuary articles that were promoted and then multiplied at the very dawn of capitalism as bearers of prestige, coveted for what they represented in the establishment of taste and style, of a notion of identity with class domination at its root. Beyond the fact that, as classical political economy would have us believe, the wig fulfils certain hygienic functions or the needs of vanity, its unchecked proliferation can be related to its appearance as an authentic language, an elaborated system of signs that, among other things, both disrupted and gave substance to the strata of the social hierarchy.

If in the early eighteenth century no one had any desire to be excluded from the euphoria of acquiring an unforeseen crowning glory, a repertoire of filamentary antennae that, to cap it all, was impregnated with essences and colours, and emitted sexually explicit messages, it should be remembered that those messages were not exclusively related to rank and well-being, but also to excess and diversion, to transgression, display and, of course, shared appetites. Those urbane antlers might have been a guarantee of good taste and status within a social code, but who would have passed up the opportunity to elevate his or her body and, from those heights, broadcast signals to the four corners of the planet? Who would have refused to play the game of adding a touch of illusion and immoderation to the language of physical presence?

* In 1760, André Charles, master wigmaker, wrote a tragedy and boldly sent it to Voltaire. The philosopher replied with a single, now famous piece of advice, repeated a thousand times over four pages: ‘Master André, make wigs, always wigs, nothing but wigs . . .’

** A century earlier Jean-Baptiste Thiers published a detailed denouncement of the clergy’s uncontrollable penchant for deceitful locks; using an arsenal of flamboyant quotations and references authorized by councils, his Histoire des peruques (A History of Wigs, 1690) is a furious compendium of the ecclesiastical misuse of hairpieces.

*** As far as is known, the Versailles fashion for wigs conquered all the courts of Europe, and only the recalcitrant Frederick William I of Prussia preferred to keep to the old military style; he did not, however, prohibit its use among his servants and subjects.

Samson at the Roland-Garros

The primitive call of hair, its unbounded fertility, that bristling which pierces and exceeds the sexual, becomes muddled and distorted when the hairpiece comes into play. Is it in fact an equally simulated force? Is some of its power transferred through contact or proximity, as happens with locks of hair in black magic? Or is it that those people who use wigs feel in some way aggrandized due to the impression created by their studied metamorphoses?

Although it is highly questionable whether Samson would have recovered his powers by using a hairpiece or toupee, this would perhaps have intimidated the Philistines and disconcerted the woman who made him lose his head without the use of a blade. When Delilah employed her wiles to carry out the symbolic castration of the man she pretended to love, she could not have been sure that the excrescence which gave him strength wouldn’t grow back overnight. Perhaps Samson – like the rebel Aristomenes of Messene, famous for his Spartan resistance, a model of courage and daring – had the ‘hairy heart’ of a lion (as the poet Vicente Aleixandre terms it) and, despite the prophecy that marked him from birth, his strength in fact sprang from his inner self rather than his hair.

As a form of media-age Samson who had to face the implacable Delilah of alopecia, Andre Agassi was haunted by the fear that his premature hair loss would lead to a decline of his strength on the courts. From childhood, his appearance had been for him a weapon, the seal of his brazen, strident understanding of tennis, only comparable with his astounding ability to return serve. By the age of eighteen, his scalp had become the main rival to be beaten in his determination to emulate the feel of concrete rather than grass, the lunar surfaces of the American Open rather than the green irregularities of Wimbledon. Was it possible for an improbable rock star of a genteel s...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- An Otherworldly Prologue

- A Theory of Disguise

- Casanova, Wigs and Masks

- The She-wolf of the Night: Messalina

- The Rage Called Wig

- Samson at the Roland-Garros

- The Counter-philosophy of the Wig

- The Future Was a Purple Wig

- The Mannequin and the Dark Object of Desire

- Andy Warhol’s Wig

- The Hemisphere in a Wig

- On the Other Side of the Mirror of Horror

- Musical Curls

- Capillary Plagiarism

- The Indiscreet Charm of Hair

- On Remains and Other Relics

- Dressing Up Justice

- Towering Hairdos

- Abbé de Choisy; or, the Inner Woman

- Cindy Sherman in Simulationland

- Death Will Come and Shall Be Wearing a Wig

- A Bald Wig in Search of a Head

- In and Out of the Theatre

- Stony Hair

- Wigs at the Extremes of Crime

- On Nudity; or, Venus in a Wig

- Reinvention by Hair

- Devotional Hairstyles

- The Chimeric Wig

- That Old Camp Stridency

- The Tangled Mop of Fetish

- A Knife Named Guillotine

- The Discourse of False Hair

- Bedside Reading

- Photo Acknowledgements