![]()

PART ONE

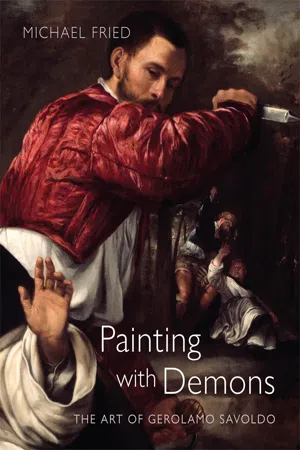

3 Savoldo, Portrait of a Young Man with Flute (illus. 37), detail.

![]()

ONE • DEATH OF ST PETER MARTYR

IN 2001 A HITHERTO unknown Savoldo of extremely high quality, the Death of St Peter Martyr, surfaced on the art market and was soon purchased by the Chicago Art Institute, where it hangs today (early 1530s; illus. 8).1 Some background: the historical Peter was a thirteenth-century Dominican friar and preacher born in Verona and active in Lombardy, often preaching against heresy (a current concern for the Dominican order in the 1520s and ’30s), who was murdered along with a companion friar in 1252. The decisive blow was from an axe to his head, and in some of the most famous depictions of the saint, such as Lorenzo Lotto’s Madonna and Child with St Peter Martyr (1503; illus. 7), or the same master’s portrait of a Dominican friar as St Peter Martyr (1548; see illus. 15), the weapon, usually a heavy knife or sword, is shown embedded in the saint’s skull (it is, in effect, his saintly attribute). (There will be more on the latter canvas towards the end of this chapter.) Savoldo’s painting, in contrast, depicts the murderous act, but does so in a manner that at once links it with other such depictions in contemporary Venice and its environs and distinguishes it from those depictions in ways that I shall try to show are revelatory of Savoldo’s unique pictorial vision.

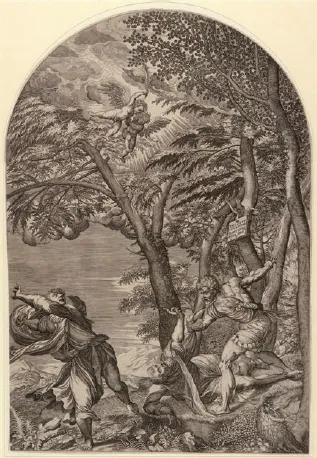

The crucial comparison, as was recognized from the first, is with Titian’s monumental altarpiece painted for the basilica of SS Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, a work of stupendous dramatic and expressive force (1529; illus. 5). The original was lost in a fire in 1867 and a replacement hangs today in its place in the Chapel of the Rosary (illus. 6). Here is Freedberg on Titian’s painting:

At an undetermined date between 1525 and 1527 a competition was held for an altar painting of the Death of St. Peter Martyr in SS Giovanni e Paolo: Titian won the contest, and in 1528–30 executed the painting (now lost, and replaced by a copy). Titian’s rivals were Palma [Vecchio] and Pordenone [a ‘provincial’ painter of formidable inventiveness and rude strength]. Palma was no challenge, but Pordenone was, and in terms that presented to Titian the same problem of a plastic style that he had faced recurrently since his indirect encounter with the Laocoon and Michelangelo [indirect because he had not actually visited Florence or Rome]. In addition, Pordenone was the exponent of the most extreme dramatic manner in contemporary art. Apparently thinking of Venetian taste Pordenone moderated his accustomed violence in his design; but apparently thinking of his competitor, Titian conceived the most radical invention he could make, exceeding Pordenone’s precedents in dramatic force, in urgency of action, and in assertion of an energy of forms expanding in their space. Articulate in form and in expression as Pordenone could not be, and far surpassing him in his descriptive means, in this picture Titian generated a vastly higher and more trenchant power. The design in which the figures act conveys the sense of an explosion: behind the figures tree-trunks act almost anthropomorphically to extend and elaborate this effect. The violence of emotion, the intensity of action, and the expansiveness of pattern are in a degree which, at least as much as in Pordenone’s or Correggio’s extreme inventions, suggests the temper of a baroque style. Yet, more evidently than in them, that end pertains to classicism. The mode of feeling of the figures is refined towards typology, and their actions have the structured grace of classical dramatic repertory; their ordering is in a scheme of counterpoise. In the setting, the explosive impetus of design is tempered as it rises, then muted, then diffused into a lyrical and tragic light. (PI, pp. 215–16)2

4 Savoldo, Death of St Peter Martyr (illus. 8), detail.

5 Martino Rota after Titian, Martyrdom of St Peter, c. 1560, engraving.

6 Carlo Loth after Titian, Martyrdom of St Peter, 1691, oil on canvas.

7 Lorenzo Lotto, Madonna and Child with St Peter Martyr, 1503, oil on panel.

8 Savoldo, Death of St Peter Martyr, early 1530s, oil on canvas.

By now Freedberg’s concern with classical norms should be unsurprising, but what I want to stress is that his account of Titian’s achievement in his Death of St Peter Martyr makes much of the competitive framework in which it was conceived, and of course Savoldo’s canvas, which scholars date to the early 1530s, must be understood not exactly as in competition with Titian’s dramatic masterpiece (Savoldo would have been perfectly aware that Titian, whom he seems to have admired greatly, could not be beaten on that ground) but nevertheless as offering a radically alternative vision of its subject. Instead of a towering vertically oriented image, such as Freedberg describes, Savoldo gives us a much more modest-scaled depiction (115 cm high by 141 cm wide), with two three-quarter-length figures, Peter and his murderer, in the near foreground and two much smaller ones, Peter’s companion and his killer, further back in space to the right. The main action consists in the assassin about to launch a backhanded blow with his dagger, which is to say that his body is turned partly away from Peter (it is sometimes said that he turns his back to him, which does not seem right), in such a way that, as was mentioned in the Introduction, emphasis falls on his crimson doublet and its folds and creases rather than on his partly obscured and shadowed face. The backhanded blow is surprising: in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings it usually precedes an attempt at decapitation with a large sword, obviously not the case here; the dagger with its curious point seems an odd weapon to be employed in such a manner. Nor is it entirely clear where the blow is intended to strike: Peter’s body seems a more likely target than his head.

As for Peter himself, the painting’s protagonist, he has fallen to his knees – the killer looms above him – and looks up and to his left, a rapt expression on his face, while as if reflexively raising his left hand before him with its palm facing the viewer. Significantly, but it is never mentioned, the hand, exquisitely delineated and painted, occupies almost the very centre of the canvas. At the same time, Peter’s brilliantly foreshortened right hand, at the lower left, makes a kind of reflexive gesture that conveys a sense of momentariness and surprise (more will need to be said about both hands shortly, as well as about the nature and direction of Peter’s gaze). Also at the lower left is a rock on which are inscribed the letters CR, standing for ‘Credo a Dio’ (impossible to make out in an illustration), in a reference to the legend of Peter’s dying act of writing the opening words of the Nicene Creed in his own blood. The killer’s left hand grips the hilt of a sword still at his side.

The setting is characteristic of Savoldo’s art in that it features a sharp division between a distant landscape (at the left) and nearer elements – often rocks but here a stand of trees (at the centre and right). The double murder takes place in broad sunlight, which casts definite shadows but mainly illuminates both the killer’s doublet and Peter’s simple but splendid white robe or surplice and copious sleeves. Mina Gregori in a short article marking the painting’s exhibition at a New York art gallery in 2001 writes that

as the light irregularly strikes the man’s doublet it bathes that splendid surface in sunshine, producing an apparent intensification of color and a sparkling quality that lends the painting its most sublime note. The calm placement of light in the friar’s habit and the assassin’s shirt captures the distinction between the various hues of white according to the way light falls, and between the luminous and penumbral areas of the picture. (p. 77)

This is acutely observed, but it is characteristic of Gregori’s stylistic priorities that no comparable closeness of observation is directed towards, for example, Peter’s facial expression.

As Gregori remarks in the same article, another version of the Death of St Peter Martyr by Palma Vecchio (c. 1529; illus. 9), in the parish church in Alzano Lombardo, a small town near Bergamo, was clearly present in Savoldo’s mind when he composed his painting (pp. 75–6). Palma’s work is a high altarpiece, and Gregori suggests, on the strength of the background trees, that it probably dates from roughly the moment of the competition, with which, however, it had nothing to do. In any case, the closeness of the saint’s pose to that of Savoldo’s protagonist is self-evident: Palma’s saint is on his knees; his right hand points to the famous sentence on the ground, which he has just written in his own blood; his left hand is very nearly in the same position as in the Savoldo; and he looks up, presumably towards the spectacular heavenly display of God the Father and a virtual ring of angels, one of which, the lowest one at the right, bears the palm branch of martyrdom. In line with other depictions of the same subject, a shortish sword is embedded in Peter’s head, while one of the assassins draws a long sword, presumably to complete the act of killing.

9 Palma Vecchio, Martyrdom of St Peter of Verona, c. 1529, oil on panel.

Obviously, though, the effect of Savoldo’s painting is altogether different from that of Palma’s, for several mutually reinforcing reasons. First, it radically undoes the distance between the viewer and the scene of martyrdom: whereas in Palma’s altarpiece the viewer is imagined as sufficiently distant to see all the figures at full length, Savoldo has moved in for the equivalent of a close-up (as mentioned, the saint and his killer are depicted three-quarter length) and the viewer is left to conclude that the saint is on his knees simply by his position relative to that of his killer.

Second, Savoldo has done away with the sense of crowding and tumult in Palma’s painting by eliminating the entire heavenly host and concentrating attention almost exclusively on the two principal figures. In Palma’s canvas, in contrast, not one but two assassins directly menace Peter, and the latter’s fleeing companion, only somewhat more distant than he, deflects the viewer’s attention to the right, further lessening the already diffuse effect of the whole.

Third, as Gregori emphasizes, the close-up framing of the scene allows Savoldo to pursue his autograph luministic and coloristic ends (never more brilliantly than here), while at the same time bringing into the sharpest imaginable focus, thereby granting a wholly new significance to, in the first place, Peter’s facial expression, and in the second his upraised left hand. Note, by the way, the magnitude of the difference in these regards from Titian’s altarpiece, in which the dramatic energy of the killing and of Peter’s companion’s flight and backwards look takes pride of place at the expense of any but the most ‘typological’ (Freedberg’s term) or indeed ‘theatrical’ (in a non-pejorative sense) physiognomic and gestural expressiveness; to speak of all the figures’ actions and gestures as belonging to a classical dramatic repertory, as Freedberg does, seems exactly right. Savoldo’s painting has none of this. In fact it could not be more deliberately removed from all such considerations (from all trace of emphatic rhetoric), a point that contemporary viewers could not but have recognized, whether in approval or not. Put slightly differently, in his Death of St Peter Martyr, knowing himself to be working in the immediate aftermath of Titian’s titanic achievement, and having gleaned useful intimations from Palma’s much less powerful but by no means uninteresting altarpiece, Savoldo found the resources to make a painting that stands out absolutely among sixteenth-century treatments of the subject – my task now being to say exactly why and how.

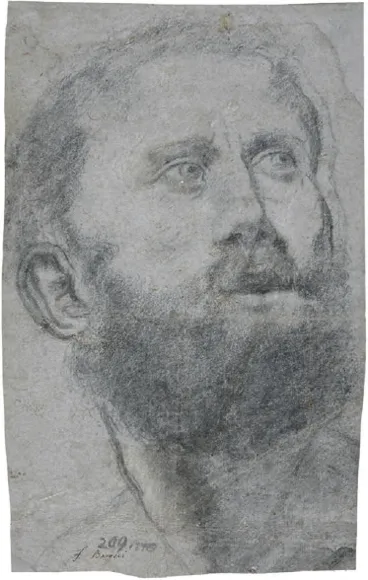

10 Savoldo, Drawing of a Man’s Head, 1530–35.

To begin with the saint’s face and expression: as Gregori noted, these are closely based on a drawing of a man’s head in Warsaw (early 1530s?; illus. 10), one of a number of extremely impressive charcoal or pencil drawings by Savoldo, all but one portrait studies of models, all but one of whom are male. In this case Savoldo had evidently already decided on the basics of his composition, and had his model – dark-bearded, with refined features, seemingly in his thirties – assume the position of the saint’s head and the direction of his gaze (towards the upper right, the model’s left). Thus Gregori: ‘In every respect . . . the correspondences are perfect, confirming the naturalism of Savoldo’s creative process’ (p. 76). But in the first place the correspondences aren’t quite pe...