- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Development schemes are common throughout the third world. Many fail, but the reasons for failure or success are only too often not adequately studied. In this monograph two schemes started in Basutoland - now Lesotho - are intensively analysed and compared: the first, which was abandoned in 1961, primarily by means of documentary material; the second, which was and still is successful in at least part of the area, mainly through observation and field research. The analysis reveals the factors making for success or failure, particularly in the fields of politics, economics, and communication. The relevance of the study extends beyond Lesotho and even Africa, the analysis dealing with problems common to introduced social change and development in any part of the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Take Out Hunger by S. Wallman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Introduction

PROBLEM

Of all emerging countries, few have a greater need for economic development than Basutoland. Even Basuto peasants are aware of this need. They know South Africa and see their country's shortcomings by comparison. They are able to picture how Basutoland might be improved. But having got so far they have neither made the effort to develop the country themselves, nor cooperated with outside agencies who have tried to do the job for them. It is quite normal for Colonial Government Schemes to fail; somewhere between planning and execution, every Scheme undertaken has broken down.

Common as these failures are, they have never been assessed, partly, no doubt, because existing governmental machinery is not equipped for self-criticism, but largely because it is felt that the analysis of failure would be fruitless. There is an assumption that nothing can be done about it, and it is this assumption that must be contested. While it is clear that no analysis as such can solve the problem of Basutoland's non-development, it is intended to show that a sociological examination of the factors of failure (and success) in past and present development projects can be of practical use in future planning, if only to the extent that the most likely points of administrative or social breakdown can be predicted and the possibility of controlling them explored. This modest level of prediction is the aim of applied anthropology (cf. Firth, 1956; Mair, 1957, 1960).

This study applies only to Basutoland and is concerned with only two of the numerous development Schemes undertaken in that country, but the usefulness of anthropology need not be confined to special cases. At least one-third of the present world is trying to improve its economic situation; the rest is, for many reasons, anxious to help it do so. Development resources are scarce and any wastage of those resources is aggravated by the urgency of the need. The regularity of failure, of a gap between what was intended and what is achieved, is both extravagant and frustrating. If the proper assessment of projects were a standard part of development policy, that gap could be greatly reduced.

Because the emphasis here is on problems of rural development, the two development Schemes are central to the analysis. Historical, ethnographic and general theoretical material is given only in so far as it illuminates those Schemes and, by extension, the problems and processes of development. The form of analysis therefore differs from that of a wholly academic study whose first and central object is the presentation and/or solution of theoretical problems, and in which any concern with practical programmes is secondary and peripheral to the main theme. No suggestion of conflict between theoretical and empirical approaches is intended. On the contrary, a combination of the two should be of benefit to both: if the assessment of actual social situations is not clarified by sociological theory, then the theory is wanting; and where else but in application can the theory be tested? (cf. Madge, 1953, pp. 8, 9; Brown, 1963, p. 32; Jeffries, 1964, p. 62 et alia).

However, in view of its first aim, the theoretical framework of this study is not and cannot be entirely homogeneous. Analysis centres on three elements which stand out to an extent that indicates they are fundamental to the success or failure of planned change. These may be summarized as (i) Politics, (ii) Economics and (iii) Communication. They are heuristically defined as follows:

(i) and (ii) – Politics and economics are subsumed under the concept of social structure as postulated by Nadel (1957). He distinguishes two principles 'defining the positional picture of societies', two criteria governing one person's structural relationship with another; the first is command over actions; the second is command over resources and benefits. In every social situation, one person or group commands the actions of the other person or group and has readier access to the resources available to either of them, if only in the limited context of that situation.

The element of situation is essential: each situation occurs in a particular 'area of social command', in one of many role frames. For the purposes of theoretical analysis, each of these role frames may be held distinct, but in matters of practical action, the individual juggles with and must somehow reconcile the competing and sometimes conflicting roles he is expected to play. In this sense, structure provides only a framework for action (Firth, 1951). Within it, the individual must assess his position and act according to priorities as he sees them. The roles or 'structural positions' are many; the man is one. Any situation involves some element of his own choice.

A number of factors ensure that the individual's choice of action is seldom unequivocal. The most cogent are: that the roles to be played are both multiple and multiplex (Gluckman, 1954); that the norms governing those roles may be ill-defined as such, and are anyway subject to different interpretations in different sectors; that a role may vary intrinsically or be altered extrinsically over time, particularly, in the latter case, by the process of deliberate social change.

The second and third of these three factors are markedly operative in Basutoland. The structural determinants of political leadership and economic command are unclear and the priorities governing action confused. The individual is regularly faced with a dilemma of choice such that whatever he does is wrong somehow. In such cases, an entirely rational choice of action is not possible. In these circumstances, the prediction of individual actions and reactions in a given situation becomes extraordinarily difficult. But even a simple descriptive statement of available options will suggest the more likely alternatives.

A description of the political and economic alternatives and pressures facing the individual is here used in the analysis of problems of rural development in Basutoland, and goes some way towards explaining the failure of the two development Schemes (cf. Brown, 1963, pp. 16-25; Adams, 1959, p. 201).

(iii) Communication in its widest sense reflects the patterns and ambiguities of the social structure, but here refers also to the matter of taking government information concerning development programmes down to the villages and bringing rural opinion up to the government. This requires both that suitable media of communication exist, and that each group is concerned to understand the other; it is compounded of both an adequate machinery of communication and a steady desire to communicate. There is evidence that both these requisites are lacking in Basutoland.

BASUTOLAND

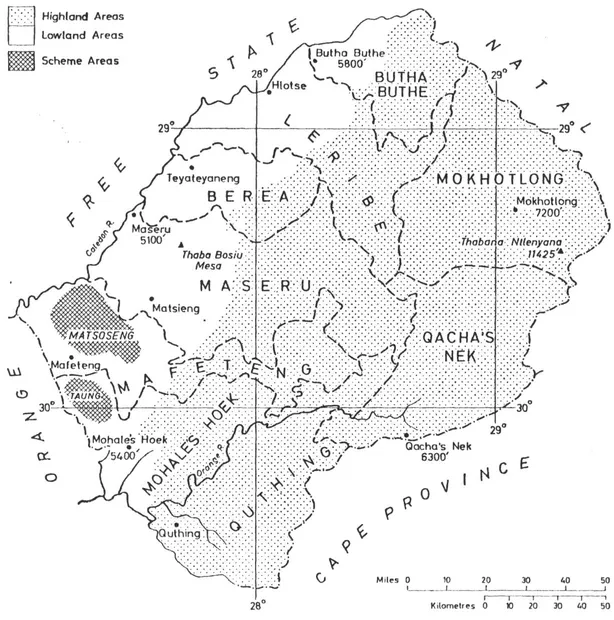

MAP. Sketch map of Basutoland, showing boundaries, main towns and scheme areas.

Basutoland is a stark, mountainous and very beautiful British dependency enclosed by the Republic of South Africa. Its total area is less than 12 000 square miles. A maximum of 1 500 of these are suitable to cultivation. Nearly two-thirds of the land area is made up of rugged foothills and mountains which are ideal for the raising of sheep and mohair goats but are generally inaccessible to the plough. On the eastern side of the country the mountains rise to nearly 12000 feet; the lowest point of the south-western lowland area is 5 100 feet. The topographical difference between the two parts of the country is so marked that the Basuto refer to them by different names: the mountains are Maluti (which is also the name of the main range) and the lowlands Lesotho (which means 'Basutoland' and is the independent nation's official name). Seventy percent of the people live in the lowland third of the country.

The present population of Basutoland is projected at between seven and eight hundred thousand. There are no non-African settlers. The British Administration, a few long-established trading families and the white element of the Missions together number only about three thousand. There is a handful of Indians in the north and a few Portuguese and Italians in the south, both groups trading, running cafés or working in building and allied trades. None of these non-Basuto groups have citizenship rights and all are regarded as temporary residents, even if of several generations standing. In principle, however, any foreigner may become a Mosuto' if he can arrange to take up land under a recognized Chief and has the permission and blessing of the Paramount.

It is estimated that about forty-five percent of Basuto men are absent at any one time and that the number of women absentees has increased in the last few years. The migration of Basuto to work over the border in South Africa is therefore a fundamental factor in the life of the country. The closing of the border on the South African side (as of 1 July 1963) has affected this population movement to the extent that migration can no longer be a matter of unregulated individual choice, but the dependence of the Basuto on wage paying jobs in South Africa is no less striking. In this sense, Basutoland might be described as a dormitory suburb of peasants who commute back and forth across the border. They do not regard Basutoland as a place of 'work', i.e. of money-making.

A very small percentage of Basuto do in fact earn regular cash incomes at home (Elkan, 1963). Aside from employment in Government or in the households of foreign residents, the raising of smallstock is the only significantly lucrative occupation open to peasants. For many mountain Basuto it is the principal if not the only source of income. Basutoland conditions produce good wool and mohair which rise to excellence if properly looked after, and wool sold to South Africa ranks as Basutoland's main export.

Little food is exported that is not effectively re-imported in the same year. Nearly all Basuto are subsistence farmers; every family that has any possibility of scratching a piece of land plants maize. Wheat and sorghum have become significant in some parts and vegetables and stone fruits do well where climate is the only consideration. The land could produce more of everything if it were fertilized, but organic fertilizers are used extensively for fuel (there are few trees in the country) and artificial fertilizers are little known and relatively expensive. The overall level of production is so low that even basic foodstuffs must be imported from South Africa.

The lack of adequate draught power is an important element in this cycle of poor production. The country depends largely on cattle to draw the plough, but the number of largestock now kept in the lowlands is too great for the water and grazing available. The normal condition of cattle is very poor. At the time of spring ploughing they are so weakened by the lean months of winter that even several span cannot turn the drought-hardened lands to the depth that a good crop demands (see Farmech Scheme, Ch. 5).

Basutoland's climate – although entirely untropical and probably very healthy – is itself a formidable handicap to nigh agricultural yields. Even lowland areas have heavy winter frosts; the mountains may be entirely snowbound and are often isolated for three or four winter months. Extreme cold and scorching sun alternate seasonally, and even daily. At any time of year an entire crop may be devastated by violent hailstorms. The air is dry; a complete absence of humidity has occasionally been registered. Rainfall is 'adequate' all over the country, but falls torrentially in short seasons. Since much of the territory is now without vegetal cover, storm water runs off unchecked, breaking up quantities of the surface sandstone and carrying thousands of tons of topsoil into and through the Republic of South Africa. Basutoland is also subject to strong winds which are bitingly cold in winter and appallingly drying in summer and which serve to accelerate the erosion of the soil.

Conditions of topography, soil type, temperature, rainfall and wind entail that Basutoland would be exceptionally vulnerable to soil erosion even if it were entirely uninhabited. These geographic factors have further combined with traditional habits of land use and with increasing population pressure to erode the soil to a degree which may be unique to the territory. Soil erosion is probably Basutoland's most urgent and serious problem. Although its urgency has been officially recognized for more than sixty years (since Annual Report 1902-3) and relatively large amounts of government money and effort have gone into repairing the cumulative damage of the past and arresting the continuous deterioration of lands, the soil continues to erode at a rate which in some areas suggests there may be none left for the next generation (see Taung Scheme, Ch. 4).

In terms of other natural resources, Basutoland is poor but unexploited. There are considerable deposits of diamonds, precious and semi-precious stones. Numerous surveys, both government and commercial, have been unable to establish whether these exist in marketable quantities, and whether inaccessible deposits could be mined economically. The country's enormous potential for hydro-electric power is, however, undisputed. The sources of several important South African waterways rise in the Maluti Mountains and there are infinite numbers of small streams and rivers. This potential is still entirely unexploited (cf. Halpern, 1965).

Basutoland's development is severely handicapped by poor communications. There are no railways except for a half mile length of South Africa's Free State line which used to bring passengers and goods into the capital (Maseru). Since the closing of the border it is only allowed to bring goods. There is a fairly extensive system of dirt roads in the lowlands. The main road runs north-south and a 'Mountain Road' goes west-east into the foothills but has stopped well short of traversing the country. There is a single stretch of tar along the section of Maseru's main street leading to the railway station. Buses, privately owned, move regularly up and down the lowland roads, but horses are still the most common form of transport amongst Basuto who can afford them. Those who cannot, walk. From the air the whole country can be seen to be covered with a complex capillary network of bridle paths which are the only surface communication in parts of the mountains. A competent commercial airline runs small plane services on schedule or charter when weather permits.

Private and government motor traffic can and does use the lowland roads, but surfaces are generally so bad that motorists who are persona grata in the Republic use the considerably better Free State, Natal or Cape Province highways. These run conveniently round the Basutoland border and are in some parts the only roads between adjoining Basutoland Districts: the driver goes out of Basutoland into the Republic, drives along a South African highway parallel to t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Preface

- Contents

- Map

- Figures

- Tables

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. POLITICAL STRUCTURE

- 3. VILLAGE ECONOMY

- 4. TAUNG RECLAMATION SCHEME 1956-61

- 5. 'FARMECH' MECHANIZATION SCHEME (from 1961)

- 6. IMPLICATIONS

- APPENDIX: ADMINISTRATION OF COLONIAL FUNDS

- LIST OF WORKS CITED

- INDEX