![]()

1

DIFFERENCE

About our tendency to clone and the pros and cons of stereotyping

![]()

Don’t Clone

Safety knows no time

I wrap my thoughts softly around your thinking.

I hear only what I want to hear.

When I doubt you and what you say, you reply: ‘all is fine,

since we’re so safe and secure together.

I rock my worries away, with you.

Our together is really ours.

I am slowly suffocating in our togetherness. I sense

how ideas are chasing their own tail. How the same

people keep doing the same things. How thoughts are slowly

fossilizing. How opinions cluster until they become sacred cows.

I claw around, looking for different views. I crack.

I open the windows of comfort and stretch my thoughts.

I breathe.

I don’t want to melt together into one same thought.

I want loose and tight at the same time. I want

ideas to clash and rub each other the wrong way.

To challenge and oppose and provoke and push me

to broaden my horizon. I want risks. I want more.

Don’t clone.

Jitske Kramer

Our encounters are nothing new ...

... we like to travel. We humans have been roaming the planet for ages, trading, fighting and falling in love. Despite our countless encounters with the unknown, we still prefer to work with people like ourselves. Just look around you in your workplace. Why do we seek out the familiar? And do we really want to be that way?

We like to surround ourselves with people who are pleasant to be with and good at what they do. We do that at school, among friends and at clubs, and definitely at work. And we tend to take ourselves as the benchmark for what is pleasant or good. Nearly everyone has had the experience of meeting a new coworker and instantly knowing whether you’ll hit it off or not. Here’s my take on this: if you immediately think you will, you have cloned. You must have felt a sense of recognition, prompted by your conscious or unconscious antenna for people who resemble you in their behavior, appearance, lifestyle or opinions. In this chapter, I’ll explain why we love and surround ourselves with people who are like us, and why we only seem able to either worship or revile people who are not like us. I’ll discuss the pros and cons of cloning; how to become (more) aware of your own cloning behavior and how you can stretch your own preferences a bit to include people who are different. You’ll find out what’s so appealing and dangerous about stereotypes, how to deal with contradictions, and what role leadership plays in diversity.

The fuss about difference: nature or nurture?

People feel safe and easy to work with when they share our basic appearance, lifestyle, norms and values, our way of thinking and solving problems. Birds of a feather flock together. It’s easy to understand each other, because we can predict each other’s behavior based on what we already know and recognize. We share the same ideas about how the game is played. This prevents embarrassment and misjudgment. You have to wonder whether this is simply what we’re made of, whether we’re incapable of peaceful cohabitation with strangers and foolish to try to change that. Then again, maybe this is all learned behavior, which implies we could change it if we wanted to.

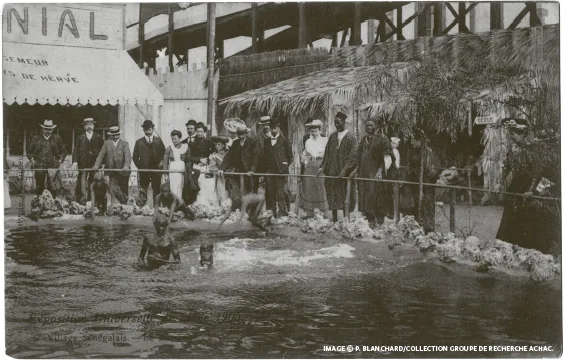

The pond in the ‘Senegalese village’ at the 1905 Liège world’s fair, postcard (heliotype), 1905. Human Zoo

Just a century ago, it was entirely normal to take your family to the human zoo to gape at socalled savages. Ethnological exhibitions were highly popular. People from all over the world were put on display for the supposedly civilized world to see what they looked like and how they lived. This black and white photograph from 1905 shows a mock Senegalese village on display at the Liège World’s Fair. It shows mothers and children bathing in a specially dug pond. It’s almost unimaginable, but these ‘freak shows’ featuring live human exhibits like Saartjie Baartman—the Hottentot Venus—or real Sami, or Inuits, actually existed!

And in some ways, they still do. It’s just that these days, we travel to where these ‘exotic’ people live, to see them in their natural habitat. We fly to Namibia to catch a glimpse of the traditional Himba lifestyle, or to Thailand to see the Padaung (better known as Longnecks) and capture them in selfies. Some of us travel to ‘save’ or ‘help’ the other, while others want contact, not so much with a particular person, but with an ideal: the romantic image of the noble savage, the natural people that still have a connection to Mother Earth and are happy, even if they have no earthly possessions. I’ll be the first to admit that I’ve been guilty of both of these motives in the past. At the same time however, I’ve always looked for a way to break out of those contexts and truly make contact with strangers as equals. This is hard work for both sides and all involved. It’s demanding, yet essential to our cohabitation as human beings.

The history of the human zoo shows how Western Europeans saw ‘the other’ less than a century ago. White people considered those of a different skin color to be barbaric. They felt superior and smugly condescended to ‘civilize’ the ‘poor darkies’. You can sense the vast inequality in these encounters, an inequality that we like to think of as long gone. However, it still lurks behind our thoughts and deeds in many ways. If not individually, then certainly on a wider, socio-economic level. Anthropology professor Gloria Wekker calls this our ‘cultural archive’, an unacknowledged reservoir of knowledge and emotions, based on 400 years of colonial domination, which continually informs our feelings, thoughts and actions without us even realizing it. From there, this reservoir spills over into our regulations, procedures, policies, teaching and institutions. This is why schools in the Netherlands often teach only half-truths about the Dutch involvement in the slave trade,. And I bet similar issues play in schools all around the world, showing mainly the positive story of the national history.

At my lectures on working in an international environment, I’m often told that the Dutch are known for their openness and tolerance for other cultures. Then I’m asked what’s stopping other nations from taking the same attitude. That’s the myth the Dutch have internalized and desperately cling to.

White innocence

Waking people up to the full story often provokes anger, disbelief, hostility and aggression. This is what Gloria Wekker, calls shattering ‘white innocence’. In her eponymous book, she argues that whiteness is “so ordinary, so lacking in characteristics, so normal, so devoid of meaning” that it has become colorless. As if being white is such a natural, invisible category that it doesn’t matter. Ethnicity is always about people of color, never about white people. In this ‘colorblind’ approach, it seems as if Dutch society is free of racism. But, as Wekker says:

“There is a fundamental unwillingness to critically consider the applicability of a racialized grammar of difference to the Netherlands. However, in the main terms that are still circulating to indicate whites and others, the binary pair autochtoon-allochtoon/autochthones-allochthones, race is firmly present …. Both concepts, allochtoon and autochtoon, are constructed realities, which make it appear as if they are transparent, clearly distinguishable categories, while the cultural mixing and matching that has been going on cannot be acknowledged. Within the category of autochtoon there are many, as we have seen, whose ancestors came from elsewhere, but who manage, through a white appearance, to make a successful claim to Dutchness. Allochtonen are the ones who do not manage this, through their skin color or their deviant religion or culture. The binary thus sets racializing processes in motion; everyone knows that they reference whites and people of color respectively.”

In 2016, the Dutch state decided that in its own communications, it would replace the terms allochtoon (immigrant) and autochtoon (native) with the descriptors “residents with a migrant background” and “residents with a Dutch background.” The change did not alter the ideas that inform our thoughts and actions. Few of us would be willing to acknowledge that we base what we say and do on underlying assumptions of inequality. We sincerely believe we don’t discriminate. “We have foreign friends,” we think. “We eat world cuisine, and had such a great time with the locals on our vacation. We’re curious, we read books...” —at least that part we know is true!— “...and we don’t judge people on their looks or gender. We’re only interested in finding the right person for the job and we don’t care about their skin color, sex or sexual orientation, how they spend their spare time, or how old they are.”

We even sincerely believe in our own sincerity. But chances are, all your friends feel the same way and when it comes down to it, like attracts like—so liberals are most comfortable associating with other liberals. More disconcertingly, it’s likely that your liberal thoughts about yourself aren’t even accurate.

White fragility

When you delve deeper into this topic, you’ll come across the term ‘white fragility’. It was coined by Robin DiAngelo in 2011, during her tenure as professor of Multicultural Education at Westfield State University. She used white fragility to describe the defensiveness white people display when challenged on their ideas about race and racism and particularly when they feel called out for white domination and privilege. Or, as Gloria Wekker puts it, when they are jolted out of their white innocence.

DiAngelo, who has twenty years of experience teaching diversity training courses, argues that white people are bad at talking about racism. As soon as this word is mentioned, they feel personally attacked, claim that they treat everyone the same, that they’re colorblind and don’t care whether someone’s red, black, white, yellow, or purple. They point out that they have black friends and demonstrated for equal rights. They raise their voices, get angry or start crying about the injustice. Those tears are known as ‘white tears’, or white people’s emotions about racism.

Why is this? In Hallo witte mensen [Hello, White People], Anousha Nzume argues that white people have the luxury of never having to deal with the color of their skin and are therefore not trained to deal with bad experiences linked to their skin color or culture. That could well be. As a white person, I experience a great sense of shame for things I knew nothing about, discomfort with my position in a larger story of perpetrators and victims in which I, my peer group and our ancestry suddenly find ourselves on the wrong side of history. And I am reluctant to share my emotions about this, because I don’t want to cry white tears. I often feel as if I have to walk on eggshells in this discussion in order not to say the wrong things. I’m afraid I’ll be misunderstood or even scolded by all sides. It’s uncomfortable. And before you know it, I stop talking about it altogether, thus reinforcing the existing inequality and accompanying racism. Mumbling a token apology to the tune of ‘color shouldn’t matter’ is nothing but a conversation stopper, masking some very real problems. It stops me, and us, from taking real action. If we stop talking out of embarrassment and the fear of saying the wrong thing, we stymie ourselves. That’s something I want to avoid.

According to DiAngelo, the strong negative emotions surrounding terms like racism and discrimination could be an unconscious defense mechanism intended to keep these problems at bay, in order not to face them, let alone solve them structurally. I hope I don’t display this mechanism myself, but I do frequently see it stifle debate in the workplace and in public. And when debate does get off the ground, it often gets clouded by a moral battle about who’s woke and who isn’t, who identified the injustice first, who is best able to handle stress, who bears the heaviest burden, who suffers most, or who is the most compassionat...