![]()

1

What Is Depressive Illness?

There are a lot of different ways of looking at depressive illness. I will touch on some of these in Chapter 3, but for now I want to focus on what I believe to be the most important aspect of it, which is this: depressive illness is not a psychological or emotional state and is not a mental illness. It is not a form of madness.

It is a physical illness.

This is not a metaphor; it is a fact. Clinical depression is every bit as physical a condition as pneumonia, or a broken leg. If I were to perform a lumbar puncture on my patients (which, new patients of mine will be pleased to hear, I don’t) I would be able to demonstrate in the chemical analysis of the cerebro-spinal fluid (the fluid around the brain and spine) a deficiency of two chemicals. These are normally present in quite large quantities in the brain, and in particular in one set of structures in this organ.

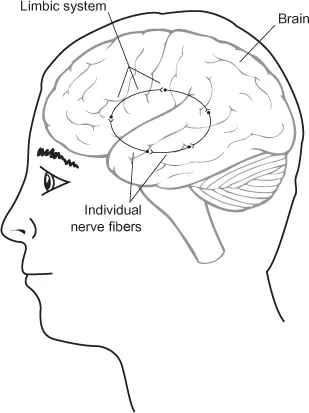

The structures concerned are spread around various parts of the brain, but are linked in the form of a circuit. This circuit is called the limbic system.

The limbic system controls a lot of the body’s processes, such as sleeping–waking cycles, temperature control, temper control, eating patterns and hormones; every hormone in the body is directly or indirectly under the control of the limbic system. It keeps all of these functions in balance with each other.

Any electrical engineer reading this book will know of the concept of a ‘reverberating circuit’. You find one of these at the core of any complex machine. For example, if a jumbo jet runs into a side wind, the pilot has to turn the tail flap to compensate, but this then means that the attitude of the wing flaps has to be changed to compensate to prevent the plane from falling out of the air. This in turn will affect the thrust required from the engines, and so on. So one change has knock-on implications for a host of different parts of the plane, far removed from each other. Something is required to orchestrate the functioning of the whole machine to compensate for changes and keep the various different parts and functions in balance. That something is a reverberating circuit, which is an electrical circuit with lots of inputs and outputs. It enables every part of the machine to ‘talk to’ every other and compensate appropriately when changes are needed. It is essentially a giant thermostat, controlling many functions at once.

The limbic system is a reverberating circuit. As well as controlling all of the functions I have already mentioned, its most important function is to control mood.

Figure 1 The limbic system

This simplified diagram shows one chain of nerve fibers. The whole system consists of millions of such chains with complex inputs and outputs which are not shown.

It normally does this remarkably well. A human being’s mood is usually very stable, given what we all go through, coming back to normal quite quickly after the ups and downs of life. We must exclude bereavement here, which is a separate process, lasting much longer than the normal time it takes for the body to adapt to major events. For everything else, mood returns to normal after a short time. For example, if you win a million dollars on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, or the lottery, or a football pool, your mood does indeed rise, for a few days. It then returns to normal, with occasional peaks, mostly in the first few weeks, corresponding with buying your first Ferrari and the like. But at 3:30 on a Tuesday afternoon, a few weeks on, your mood is no different than it was before the life-changing event occurred.

So mood isn’t controlled consistently by events or the quality of your life, but by the limbic system. It is this circuit that determines, in the long term, the level of your mood. It is, if you like, the body’s ‘mood thermostat’.

But like every other system and structure in the body, it has a limit. If you bash a bone hard and consistently enough, it will break. So will the limbic system.

It can be caused to malfunction by a number of different factors. These include viral illnesses such as the flu. Most of us have experienced a degree of post-viral depression. It is very unpleasant and debilitating, but normally passes quite quickly. Sometimes it does not and leads to a fully blown clinical depressive episode. Incidentally, don’t confuse this with ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’ or myalgic encephalopathy (ME), which is a separate and very nasty condition, though it also tends to follow viral illnesses.

Other precipitants of limbic system dysfunction are hormonal conditions, illicit drugs, too much alcohol, some prescribed medicines, too many major life changes, too many losses or facing choices involving conflicting needs.

By far the commonest trigger, though, is stress.

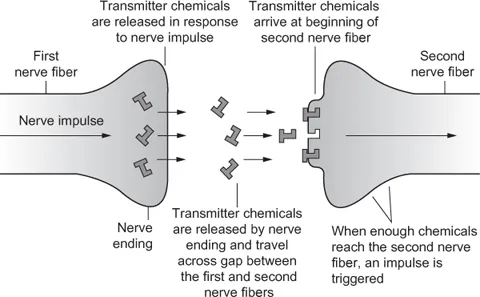

Whatever the cause, the end result is the same. If the limbic system is taken beyond its design limits, it will malfunction. The part of it that goes is the gap between the end of one nerve and the beginning of another, or the synapse. There are millions of these in the limbic system and they are the most vulnerable part of the circuit. A nerve fiber is essentially a cable. Once a nerve impulse starts down a nerve fiber, it reaches the end without difficulty; the tricky bit is getting the impulse across the synapse. This is done by the first nerve releasing chemicals into the synapse in response to the arrival of an impulse at its end. These chemicals travel across the synapse and when a sufficient quantity of them arrives at the beginning of the next nerve fiber, an impulse is triggered off.

Figure 2 A synapse in the limbic system

Thus the gap is crossed by the nerve impulse and the circuit keeps running.

In clinical depression it is these transmitter chemicals which are affected. In response to stress or any of the other triggers, the levels of these chemicals in the synapses of the limbic system plummet (and the nerves probably get less sensitive to the chemicals, too). As yet we don’t know for sure why this occurs, but it does, and when it does the circuit which is the limbic system grinds to a halt.

The transmitter chemicals thought to be involved are serotonin and noradrenaline, with two other chemicals, dopamine and the hormone melatonin, more recently discovered also to be in the picture. The truth is we don’t know for certain how these chemical and nerve systems work. The more we learn about the limbic system, the more we realize we don’t know. Isn’t that always the way? Nonetheless, it is still clear that chemical changes in the limbic system are important in the development of depression.

When the limbic system malfunctions, a characteristic set of symptoms arises. These symptoms are what define clinical depression and separate it out from other states, such as sadness, disgruntlement or stress. There are some conditions, such as glandular fever, an underactive thyroid gland or ME, in which some of the symptoms are the same and someone under a lot of stress may have some of them; but if you have all or nearly all of them, you have clinical depression. Most of these symptoms are under the heading of ‘loss of’. It’s pretty much a case of loss of everything – it is as if the whole body shuts down and, as I will outline later, this is possibly what is happening.

Symptoms in Clinical Depression

Feeling worse in the morning and better as the day goes on. Loss of:

•sleep (usually early morning wak...