- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this volume, J. Gerald Janzen examines the text of the book of Job as a literary text within the context of the history of the religion of Israel and within the broader context of the universal human condition. He approaches the basic character of the book from a literary perspective which enables him to identify human existence as exemplified in Job and to expound on the mystery of good and evil, which gives human existence its experiential texture and which together drive humans to ask the same kind of questions asked by Job. This is the first full-length commentary to present Job systematically and literarily.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Job by J. Gerald Janzen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Commentary. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Prologue

A Dialogue of Heaven and Earth

JOB 1—2

The prologue begins (1:3) and ends (2:13) on the theme of Job’s greatness. Whereas his earlier greatness is one of moral stature and material prosperity, his latter greatness is measured in terms of physical and existential anguish. Job’s earlier condition has arisen through the fact that he has been cradled and nourished within the life-giving orders and structures of the natural, social, and religious-symbolic world; and his piety and uprightness are his grateful response to God for life within such a “hedge.” Then the question arises in heaven: Is Job’s piety tied to the cradling and nourishing conditions of his life? Is it only a conditioned response? Or may it be that he is capable of a piety freely given? The question which arises in heaven is not answered there (for that would keep him within the hedge) but is given into Job’s hands to answer (thereby conferring upon him a terrible dignity). The hedge is breached through a succession of calamities. His first response takes the form of conventional actions and words, those symbolic means by which one’s world remains hedged about when calamity strikes one physically and socially and materially. Gradually, however, even the hedge and cradle of his inherited belief-structure shows signs of stress and strain, and by the end of the prologue he is entering silently into a strange realm of naked and solitary suffering.

* * *

On the Structure of the Prologue

It is commonly observed that the Book of Job comprises a series of poetic dialogues preceded and followed by prose narratives. The book may thus be said to exemplify Robert Alter’s generalization that biblical literature manifests a pronounced preference for dialogue. Alter writes:

The biblical writers, … are often less concerned with actions in themselves than with how individual character responds to actions or produces them; and direct speech is made the chief instrument for revealing the varied and at times nuanced relations of the personages to the actions in which they are implicated (The Art of Biblical Narrative p. 66).

The reasons for this preference he attributes to the Hebrew preoccupation with interaction of wills and with the role of language both in effecting and in disclosing the intentions of wills, human and divine. He writes again,

Spoken language is the substratum of everything human and divine that transpires in the Bible, and the Hebrew tendency to transpose what is preverbal or nonverbal into speech is finally a technique for getting at the essence of things… (p. 70; italics added).

These generalizations are eminently applicable to the Book of Job. Yet we should not therefore suppose that the prologue may be read quickly in order to get to the “real meat” of the dialogues. For one thing, the prologue itself contains a good deal of dialogue; furthermore it displays a density of literary form and theological content which claims reflection and comment out of proportion to its comparative length.

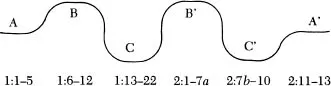

One should note, first, that the prologue itself is emblematic of the structure of the book as a whole. An almost completely narrative introduction (1:1–5) is followed by several largely dialogical scenes (1:6—2:10), and these dialogues are followed by a narrative conclusion (2:11–13). The dialogical scenes in the prologue, however, transpire on two levels, heaven and earth. We may schematize the prologue as follows:

Within each level the dialogue proceeds on a horizontal axis between inhabitants of that level (that is, between Yahweh and Satan; and between Job and messengers/wife). But insofar as each dialogical scene arises in response to something on the other level, the sequence ABCB’C’A’ may itself be said to signal an implicit dialogue moving along a vertical axis. Elsewhere in the Bible, vertical dialogue between heaven and earth often is rendered explicitly. In Job such a rendering is given only at the end, in the divine speeches; yet it is present implicitly already in the prologue, as an inkling of the biblical vision generally. The importance of this last observation lies in the foreshadowing function of the structure of the prologue. Taken by themselves chapters 3—37 might be supposed to present simply a horizontal dialogue of the sort C/C’. Against the background of the prologue (and in view of the way in which, as we shall see, dialogue C’ echoes elements of dialogue B’), chapters 3—37 are seen to present also the human pole of an implicit vertical dialogue with heaven. This observation is reinforced by 3:2 which says in Hebrew, “and Job answered and said,” and by the frequency with which Job in chapters 3—31 addresses heaven directly. Divine silence and human verbal doubt too often in religious circles are taken to signal the deterioration or the breaking off of the vertical dialogue. Already through its structure the Book of Job presents both the silence and the verbal doubt as modes in which that dialogue continues unruptured and unabated.

We have observed that the dialogue transpires on two levels, heaven and earth, as though we should envisage a universe of at least two levels—or, with an eye to Job’s frequent references to Sheol, of three levels. But (in the spirit of Robert Alter’s remarks on the biblical preference for dialogue over narration for the sake of penetration to the personal essence of things) we suggest that this spatial imagery in Job is secondary to and elucidatory of a primary preoccupation with realms of personal presence. The actions and words of the prologue, like those of the rest of the book, center in two personal loci: the presence of God (e.g., 1:6 and 1:12b) and the presence of Job (e.g., 1:14a and 2:11). One may say that God is in heaven and Job on earth. But it is truer to say that the Joban drama is dominated by and played out within the realm of two personal presences and that terms like “heaven” and “earth” have their meaning as spatial ways of indicating those two presences. In such a perspective, of course, Sheol becomes a peculiar “realm” (see, e.g., 18:14), a realm of sheer negativity devoid of any presence human or divine, a “place” or rather “no-place” where, in the words of Dilys Laing, “all is solitary,” a place where “I shall discover forever my own absence” (Dilys Laing, p. 27). In such a view, the Book of Job may be taken as an exploration of doubt and silence, not only as modes of dialogue but also as modes of presence.

Job 1:1-5

Narrative Introduction to Job Himself

What’s in a name? Job, ’iyyob, seems to have developed from a well-attested second-millennium West Semitic name of a sort which fell into disuse in the first millennium (Marvin Pope). That name, ’ayya-’abum, “Where is the (divine) father?” places Job within the ambience of Israelite ancestral personal religion with its reference to God as divine parent. In such a setting Job’s name is a standing invocation of God’s presence in his life. Robert Gordis, however, explains the name as a passive participial noun (from ’ayab, “to hate”) meaning “the hated, persecuted one.” We may not have to choose between these two proposals. Word-plays through secondary etymology are a common device in biblical narrative. In the present instance we may have the combination of traditional meaning (“where is the [divine] father?”) and novel association through sound-similarity (“the persecuted one”) to achieve a word-play in which the very name Job poses the problem for the book and for Israel in exile. Does Job’s experience not change the meaning of his own name? Does his sort of experience any longer justify the use of parental metaphors for God? The very name Job, which once was a confident invocation of God as divine father, now becomes an accusation against God as enemy and persecutor.

Modern commentators cannot be sure of the precise location of Uz. Nor do the places reflected in the biblical occurrences of this place name suggest that the Israelites were any clearer on the question. Was the name chosen for this reason? Narratively, then, the names “Job” and “Uz” introduce the story as happening “long ago and far away.” Such distancing can serve many purposes. In this instance it may signal the writer’s attempt to achieve (and it may invite the reader to enter into that achievement of) some perspective on a problem which, considered in its present immediacy, would be so overwhelming as to render even clarity of questioning all but impossible. Prior to any provisional resolution of problems, prior even to specific lines of questioning, the capacity to distance and then to entertain the problem imaginatively already signals the emergence of elbow room within severe straits and thereby signals the mute presence and operation of grace.

This Job, who (as his name suggests) owes his birth and his idyllic prosperity (vv. 2–3) to the care of his personal God, makes exemplary response to God through his piety and his moral conduct. This exemplary response is described by two pairs of phrases: (1) he is (a) blameless [tam] and (b) upright [yašar]; (2) he (a’) fears God and (b’) turns from evil. yašar, commonly translated “upright,” more precisely describes straightforwardness of conduct as along a straight path. Proverbs 4:25–27 shows how such straightforwardness can be placed in a poetically parallel relation with turning from evil. So also here in 1:1, such straightforwardness (b) is seen to be in a parallel relation with turning from evil (b’) and thereby as synonymous with it. This means, then, that (a) “blameless” stands in a parallel and synonymous relation to (a’) “fearing God” and so refers to the character of Job’s piety. (For future reference, it should be noted that the adjective tam, “blameless,” is cognate with the noun tumma, which RSV translates “integrity.”) According to the general meaning of the word tam, piety so described is not nominal, flawed, or partial, but genuine, whole, and complete; and it constitutes the central principle of Job’s individual integrity. Taken together, the two pairs of expressions in 1:1 sum up the Israelite conviction as to the distinguishable but inseparable relation between authentic piety and genuine morality.

It will remain for the speakers in the following heavenly scene to suggest, or rather to question, the precise nature of the causal relation between Job’s piety/morality and his prosperity. For now one may note simply that in respect to both his piety/ morality and his prosperity this man was without peer in his society. For verse 3b does not refer only to verses 2–3 (as implied by RSV punctuation) but to verse 1b as well. Formally, then, if the pairs of phrases in verse 1b express the connection between piety and morality, the structure of verses 1–3 expresses a sense of the connection between these two and prosperity.

By the way in which they set forth Job’s exemplary piety and moral character, and his idyllic prosperity, verses 1–3 may give rise to a sense of the distance between Job and the circumstances of the reader; but that distance is immediately closed by the means which the narrator uses to solicit our sympathetic identification with this figure. Bearing in mind Robert Alter’s comment on the use of dialogue to penetrate to “the essence of things,” we note the effect achieved by concluding verses 1–5 with an interior monologue. Following an external portrayal of the man and his situation in life, we are taken inside his heart and mind, where we discover that he shares the common pathos of parental concern—a concern and a pathos which, for all that a parent may wish to do and may be able to do, in its helplessness finally can enact itself only in symbolic action heavenward—over what his children may do in the blithely heedless activities and spontaneous projects of youthful zest. Those youthful doings are set in the context of the children’s celebrations “each on his day,” a reference, in our view, to the celebration of birthdays (cf. 3:1, where Hebrew “his day” is correctly translated “the day of his birth”).

As a birthday the feast is of great importance. For in celebrating a birthday one affirms not only an individual life but the generativity and general goodness of the world under the creative generosity of God; and one invokes the powers manifested on that day—its energies of blessing and its good auguries—by way of renewing one’s life for another year. No other day has such a claim to be called “one’s day.” Indeed, it may be suggested that, while all other feasts are primarily communal in their focus, the feast of one’s own birthday is a fitting component in the “personal religion” within which we have situated Job.

Now, construed as a day of birth, “on his day” resumes and advances the generative theme of verse 2. But in verses 18–19 the fourth and climactic calamity falls on just such a birthday feast, moreover the feast day of the eldest or, as the Hebrew puts it, the “firstborn.” The catastrophic intersection of such a reality-affirming feast and such a calamity in the sharpest manner challenges creatural piety toward God as divine parent and giver of generativity and protection. The depth and the severity with which Job feels this challenge are registered in the words with which he breaks his long silence in chapter 3, words with which he curses “his day” (3:1). But in the first instance he meets this challenge with an affirmation couched in the imagery appropriate to the piety of personal religion (1:21) and its generative theme.

Job 1:6-12

First Scene in Heaven:

A Question Which Sets the Drama in Motion

It was suggested above (“On the Structure of the Prologue”) that though the four scenes transpire alternately in heaven and on earth, yet each scene on one level arises in implicit dialogical response to the preceding scene on the other level. In the present instance, B (in heaven or, better, in Yahweh’s presence) follows aptly from A (1:1–5) in a number of ways. For one thing, the relation between A and B exemplifies in sustained fashion Robert Alter’s remark that

the primacy of dialogue is so pronounced that many pieces of third-person narrative prove on inspection to be dialogue-bound, verbally mirroring elements of dialogue which … they introduce (p. 65).

In particular, the coming together of the “sons of Job” on a given one’s “day” is matched by the coming together of the “sons of God” on “a day” or, as the Hebrew reads, on “the day.” Jewish Targumic and Midrashic tradition identifies this as New Year’s Day (Gordis). In Mesopotamian religion the gods assembled on New Year’s Day to determine destinies for the coming year. Given that such a New Year’s Day celebrated and renewed the creation of the cosmos with all its life-giving powers, the associations between verses 4–5 on the one hand and verses 6–12, 18–19 on the other are all the more effective as suggesting the full implication of Job’s troubles.

In view of the strident monotheism (however “non-philosophical”) of the Old Testament, the imagery of the divine council here and elsewhere is easily dismissed as merely a poetic and concrete way of portraying the divine governance of the world. Such a move should not be made glibly. In this instance at least the poetic imagery lends itself to the exploration of a profound theological—or rather, since the question is posed from the divine perspective and about Job, a profound anthropological—question. That such anthropological questions can in Israel be attributed to God is evident from Hosea, where a series of divine questions gives expression to a struggle within God over Israel. James Luther Mays, commenting on Hosea 11:8–9, goes so far as to write of an “intense … impassioned self-questioning by Yahweh” (p. 156). We have argued elsewhere (Janzen, Semeia, esp. sections 1.11, 1.21, 1.31) that in Hosea those questions ought to be given great weight in our reflections on the nature of God and on the character of the divine-human covenant relation. Of course, in Hosea the questions arise over the covenant infidelity of Israel, whereas here they arise over Job’s fidelity and have to do with its ground and character. In the latter instance the imagery of the divine council, with the Satan as a proper member, serves as a figural means to explore the possibility of the rise of a particular existential question within the life of God, a question which, shared with Job, becomes an existential question for Job and through him for humankind. The divine existential question is not resolved unilaterally or in solitary fashion within God. Rather, it is shared with Job through the import which his own experience has for his own questioning (see esp. the commentary on chaps. 9—10, the section 9:32–35). It is shared with him also through the Yahweh speeches and the epilogue. Also it is shared explicitly with the reader who, unlike Job, is given the privilege of access to the scene in the divine council. Furthermore, the question even for God is resolved only through the manner of Job’s own response to his experience. If one views the shared exploration and resolution of existential questions as establishing one sort of covenant relation, then the Book of Job may be taken as one attempt to re-vision Israel’s covenant relation with Yahweh, finding in that relation hitherto unsuspected implications and placing it on more deeply probed bases.

Classically in Israel the vision of the divine-human relation took as its point of departure the parent-child metaphor of Mesopotamian personal religion. That metaphor is reflected prominently in the ancestral narratives of Genesis. Even where the central metaphor was not so much n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title Page

- Interpretation

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Series Preface

- Preface

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- Dedication Page

- Introduction

- Part One:

- Part Two:

- Part Three:

- Part Four:

- Part Five:

- Part Six:

- Part Seven:

- Bibliography