- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

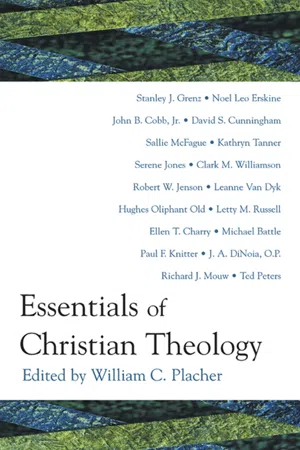

Essentials of Christian Theology

About this book

This splendid introductory textbook for Christian theology presents two essays by leading scholars on each of the major theological questions. William Placher provides an excellent discussion of the history and current state of each doctrine while the essays explore the key elements and contemporary issues relating to these important theological concepts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Essentials of Christian Theology by William C. Placher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

How Do We Know

What to Believe?

Revelation and Authority

“Our church teaches you have to be baptized as an adult.”

“I just can’t believe in the Virgin Birth.”

“Homosexuality is a sin—it says so in the Bible.”

“You can’t take the Bible literally.”

We hear such comments all the time, and they remind us that Christians disagree with each other about what to believe. Sometimes individual Christians even disagree within ourselves—new ideas come into conflict with the faith we were taught as children, and we struggle to make up our minds.

If two people disagree about the answer to a math problem, we go back to check our figures. If two scientists reach different conclusions, they go back to review their data. How do Christians argue? How do we decide what to believe?

REASON AND REVELATION, SCRIPTURE AND TRADITION

We might try to decide theological questions the same way a mathematician or scientist would—through the use of our reason. Two hundred years ago, the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant tried such an approach in a book entitled Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone. Brilliant as the book is, most philosophers think it reaches beyond the limits of reason, and most theologians argue it falls far short of Christianity. A long tradition in theology has held that, even if people could reason their way to belief in God and some sort of moral code, Christian doctrines like the Trinity and salvation through Christ are inaccessible to reason.

The role of reason in theology, however, cannot be explained by drawing a sharp line between what reason can know and what it cannot. Whatever other topics it addresses, theology inevitably talks about God, and Christians generally agree that human reason by itself is inadequate for understanding God. To start with, God is infinite, and we are finite. We are too limited to be able to make sense of God. Moreover, sin has corrupted what capacities we have, and any idea we developed of God on our own would be distorted on that account.

Theologians have disagreed about the extent of that distortion. Historically, Roman Catholics have held that, even though we are finite and sinners, our reason can provide some truths about God. Aquinas, for instance, began his discussion of God with five philosophical arguments for God’s existence (more of that in the next chapter). The Protestant Reformers Luther and Calvin both believed that whatever truth reason might provide about God was, thanks to sin, so mixed with error that it was best not to depend on it. Both Protestants and Catholics, however, have agreed that we cannot figure out for ourselves anything like an adequate knowledge of God. For that, we have to depend on something God gives us—revelation.

Theologians thus fall along a spectrum, from those at one end who trust almost entirely in reason, to those like Barth at the other, who put all or almost all their trust in revelation.

To emphasize that all our knowledge of God comes from God, theologians sometimes call what we can figure out by our reason general revelation, in contrast to what God gives us in Scripture or other particular sources, which they call special revelation. Natural theology is another name for general revelation—the part of theology we learn through the study of nature rather than Scripture. As noted in the introduction, the great early-twentieth-century theologian Karl Barth warned against natural theology. He argued that human reason is shaped by our culture, and therefore natural theology, based on reason, can lead us away from Christian faith into beliefs about God shaped by the values and assumptions of our particular culture.1 Theologians thus fall along a spectrum, from those at one end who trust almost entirely in reason, to those like Barth at the other, who put all or almost all their trust in revelation.

Catholics and Protestants have also traditionally seemed to disagree on where to find that revelation. Sola scriptura (“Scripture alone”) was one of the slogans of the Reformation. When his opponents sought to prove him wrong by appealing to decisions of popes and councils of the church, Martin Luther, in a famous and dramatic moment in 1521, stood before the emperor and assembled nobles of Germany and declared,

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of Scripture or by clear reason, for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves, my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not retract anything.2

In response, at the Council of Trent a generation later, the assembled Catholic leaders made explicit what Catholics had widely assumed for a long time—that there were unwritten traditions passed down through the church which had authority alongside that of Scripture.3

Recent discussions between Protestants and Catholics have found more agreement than the slogans of the Reformation era would imply. There were Christians, after all, before there was a Bible. Protestants have to admit that those first Christians must have been dependent on traditions passed down among them and that traditions still shape the way we read the Bible. Catholics acknowledge that traditions function primarily to point us back to the truth of Scripture.

Medieval theologians discerned four senses in Scripture: the literal, the allegorical, the tropological, and the anagogical.

However much theology depends on revelation, and wherever theologians look for that revelation, revelation requires interpretation, and that generates further questions. From the early centuries of Christianity some theologians argued that some passages in the Bible could not be literally true and therefore must be understood in some other sense.4 If the Bible talks about the “hand of God,” for instance, it does not mean that God literally has hands. Likewise, it seemed to most medieval interpreters that the rather erotic poetry of the Song of Solomon could not be literally about a love affair between a man and a woman. It must refer to the relation between Christ and the church, or God and the soul. Eventually, medieval theologians discerned four senses in Scripture: the literal sense, the allegorical sense (which applied to Christ and the church, and could also be used as a general term for any nonliteral sense), the tropological sense (which applied to our lives), and the anagogical sense (which applied to the last days or heaven). So, for example, when the Bible talks about Jerusalem, it can refer to the city in the Middle East (literal), the church (allegorical), the soul of the believer (tropological), the heavenly Jerusalem (anagogical), or all four—or some combination of them.5

Even in the Middle Ages, theologians debated how much emphasis to put on the nonliteral senses. While the Reformers did not abandon allegorical interpretation altogether, they did emphasize the literal sense. Still, they exercised considerable freedom in interpretation. Luther thought that justification by grace through faith was the core of biblical teaching. He treated texts that did not speak to that theme with indifference or hostility. He admitted that he did not know quite what to make of the book of Revelation and dismissed the Letter of James as a “letter of straw,” claiming that “it does not amount to much.”6 Calvin was more cautious, but he too acknowledged that the Gospel writers “were not very exact as to the order of dates, or even in detailing minutely every thing that Christ said and did.”7 The truth of the Bible did not depend on the literal truth of its every proposition.

In the seventeenth century, pressure grew to “prove” that one was right, and many theologians adopted one version or another of the scientific method as the definition of a good argument.

In the seventeenth century, however, debates among the different branches of Christianity intensified, and pressure grew to “prove” that one was right and one’s opponents were wrong. In an age when science was growing in importance, many people adopted one version or another of the scientific method as the definition of a good argument. The Westminster Confession of Faith, written by Reformed Christians in England in 1647, already says that everything that we need to know for our salvation “is either expressly set down in Scripture, or by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture.”8 Like scientists, the Westminster Fathers claimed they could deduce their conclusions from indubitable assumptions. In the centuries since, many theologians have continued to follow that model of looking for clear starting points for theology in revelation, but in thinking about revelation, they have chosen either a propositional model, a historical model, or an experiential model.

THREE MODELS OF REVELATION

1. A propositional model of revelation, already implied by Westminster’s language of “expressly set down in Scripture,” has taken clearest form among conservative American Christians beginning in the nineteenth century. As the evangelical theologian Carl F. H. Henry puts it, “The whole canon of Scripture . . . objectively communicates in propositional-verbal form the content and meaning of all God’s revelation.”9 Quoting Gordon Clark, Henry states succinctly, “Aside from imperative sentences and a few exclamations in the Psalms, the Bible is composed of propositions. These give information about God and his dealings with men.”10

For the most uncompromising propositionalists, biblical truth is an all-or-nothing deal. The Bible is a set of propositions. If we start questioning any of them, then there will be no place to stop, and soon we will not be able to trust the truth of anything in the Bible. Therefore, the Bible must be inerrant—all of its propositions must be true. But even within a propositionalist model there is room for alternatives. Some who insist on the inerrancy of the Bible as originally written (the autograph) acknowledge that the biblical manuscripts available to us differ, and therefore admit that existing biblical texts can contain minor errors. Others go further and say that God’s purpose in giving us the Bible is to lead us to salvation, so only what concerns salvation in it need be true.

For the most uncompromising propositionalists, biblical truth is an all-or-nothing deal. The Bible is a set of propositions. If we start questioning any of them, then there will be no place to stop.

To take some contemporary North American evangelicals as examples: Harold Lindsell holds that the original biblical writings were inerrant and that God has protected key manuscripts so that we still have inerrant texts. Carl Henry says that the original texts were inerrant but minimal errors may have slipped into the manuscript tradition since then. Clark Pinnock defends the inerrancy of the intention and meaning of the texts as we have them, but not of their specifics. Bernard Ramm believes the Bible is inerrant with respect to knowledge needed for salvation, but not concerning historical and scientific matters. Donald Bloesch affirms the inerrancy of major theological assertions, but holds that some religious and moral assertions in the Bible, as well as historical and scientific claims, may be in error.11 The unqualified inerrantists face the challenge of explaining what seem inconsistencies in the Bible or defending claims it makes about science or attitudes it takes toward slavery or the position of women or other issues where what the Bible says makes many readers today uncomfortable. They in turn challenge those who introduce qualifications as to how they can know where to stop once they have admitted the possibility of some biblical errors.

2. The German Lutheran theologian Wolfhart Pannenberg is the most distinguished representative today of a different approach, a historical model of revelation. For Pannenberg, God is revealed not in the propositions in the Bible but in the events that they report. God is revealed, for example, not in the fact that the Bible says Jesus was raised from the dead, but in the fact that Jesus was raised from the dead. Believers in the propositionalist view have to explain how we know that the Bible is inerrant by some appeal to faith. In contrast, Pannenberg insists that on his view: “The historical revelation is open to anyone who has eyes to see. . . . God has proved his deity in this language of facts.”12

For Pannenberg, God is revealed not in the propositions in the Bible but in the events that they report.

Pannenberg argues that history tests the truth claims of various religions. For instance, worshipers of Marduk in ancient Babylon believed that Marduk was the most powerful of gods and would always bring them victory. But the Babylonian empire was ultimately destroyed. History proved them wrong. Religious folk dream dreams and make prophecies, but “signs are either borne out or not. Dreams come true” or not,13 and such results determine the truth of the religious claims.

Since religious claims concern the whole of reality and we are only in the midst of history, Pannenberg admits, we can only say that the evidence so far tentatively supports Christian faith. But Jesus’ resurrection anticipated the end of history; what happened to him offers the central clue about how all of history will turn out. Since Pannenberg thinks there is good evidence that Jesus was raised from the dead, he concludes that Christians are justified (if still tentatively) in their convictions concerning the shape of history as a whole and therefore in their beliefs concerning what God reveals in history.

Back in the 1950s, many adherents of the “biblical theology” movement made a similar appeal to history as th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Why Bother with Theology? An Introduction

- 1. How Do We Know What to Believe? Revelation and Authority

- 2. What Do We Mean by “God”? The Doctrine of God

- 3. Is God in Charge? Creation and Providence

- 4. What’s Wrong with Us? Human Nature and Human Sin

- 5. How Does Jesus Make a Difference? The Person and Work of Jesus Christ

- 6. Why Bother with Church? The Church and Its Worship

- 7. How Should We Live? The Christian Life

- 8. What about Them? Christians and Non-Christians

- 9. Where Are We Going? Eschatology

- A Basic Chronology

- Christian Denominations

- Glossary of Names and Terms

- Notes

- Index