![]()

1

Philippians 1:1–11

Joy and Thanksgiving for the Philippian Congregation

Let us imagine for a moment what it might have been like to be a member of a Christian community in Philippi near the middle of the first century. We are part of a tiny (nearly invisible), ragtag minority, made up mostly of people who, like the vast majority in Philippi and other cities of the empire, live in daily poverty. We depend on one another and on good relations with our neighbors and the governing authorities just to survive. We have heard the proclamation of a band of Jewish missionaries, led by Paul, that the God of Israel took human form and died on a cross outside Jerusalem but was raised from the dead. This vision of God is fundamentally different from anything we have ever heard about Gods before, even about the God of Israel. We also know that to proclaim this Jesus as “Lord” puts us at risk with the Roman authorities, who claim in their propaganda that peace, salvation, and justice (or righteousness) are all gifts of the emperor to the conquered world. Rome demands of us our faith (or loyalty), which is now complicated by our new loyalty to the God we know in the stories of Jesus Christ. We have continued to support Paul financially and spiritually as he pursues his mission in other cities; but now we hear that Paul himself has been arrested by the Roman authorities. He is writing to us from jail. What feelings would we have as we first heard this letter from Paul read aloud in our household church?

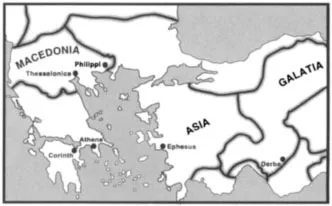

Philippi during Paul’s travels

Philippians was written to address just this situation, to deal with the tensions and anxiety that inevitably arise when people hear disturbing news about their founding teacher. To address these needs, Paul goes back to the foundations, reminding his friends who God is, and what the gospel of Jesus Christ is about. He spells out the implications of the Gospels with regard to the particular strains felt within the congregation. He reminds them of the relationship they have had with him in the past, and he encourages them to continue to nourish it.

Philippians 1:1–2: A Provocative Salutation

Contemporary readers of Paul’s letters might be tempted to merely glance at the introductory greetings or skip them altogether, since the most prominent information found in them—names, places, and what appear to be formulaic greetings—presumably have little to do with the real meat of the letter. Paul’s greetings do, in fact, follow a pattern that was typical for his day, yet they convey a wealth of information that alerts astute readers to the mood, purpose, and content of the whole letter. The greeting includes a “signature” that identifies the writer and his colleagues, an “address” naming the recipients, and the “greeting” proper (Craddock, 3, 11–14).

The signature in Philippians (1:1a) identifies Paul and Timothy as co-senders (Timothy is also named in the signatures of 2 Cor., Col., 1 and 2 Thess., and Philemon). We do not know whether Timothy actually had a hand in writing the letter itself, especially since Paul uses the first person singular “I” throughout this letter. According to Acts 16, Timothy was present with Paul at the founding of the Philippian church and made a later visit as well (Acts 19:22). At the very least, naming Paul and Timothy together identifies them as parts of a team and affirms Timothy’s authority in preparation for his visit to Philippi (Phil. 2:19–24). Still more important, however, is the designation applied to both Paul and Timothy: “servants (or slaves) of Christ Jesus.” Slavery, or servanthood, will play a prominent role in the letter, designating the human form taken by Jesus (2:7), as well as the attitude and practices of Timothy in his work with Paul (2:22). More generally, it suggests something of the fundamental self-understanding and orientation toward others that Paul wants to hold up for the Philippians to imitate. By naming himself and Timothy as slaves of Christ Jesus, Paul indicates that his identity and honor—a matter of crucial importance in Paul’s world—are tied inextricably to Jesus Christ, the one who has made known God’s true nature by taking the form of a slave and dying on the cross (2:6–8). As “slaves,” Paul and Timothy belong to Christ Jesus; their calling and destiny correspond with his. Hardly a casual designation, the identification of Paul and Timothy as slaves takes on even more texture as we consider the situation of those to whom Paul writes.

The address (1:1b) has several components and, like the signature, appears at first glance to be simpler than it really is. “To all the saints” may sound as if it names the holiest of the Philippian Christians, those whose character is beyond reproach. The term “saints” did suggest something of the moral character of those who followed God faithfully, but at its primary level it refers to God’s claim upon those whose lives are bound up with God in a covenant relationship. God’s call and claim separated “the saints” from the world so that they might dedicate themselves to service and worship. This does not mean that they lived physically separate from the world, but that God rather than the world laid claim to their imagination, vision, and practices. They are “God’s people” rather than “the world’s people.”

Paul also identifies the addressees more particularly as saints “in Christ Jesus” and “in Philippi.” The phrase “in Christ Jesus” suggests that Christ is both the location in which the Philippians have rooted their identity and the source and sustaining power of their new life. Some scholars point to the ancient conception of “corporate personality” or “the one who stands for the many” in order to clarify this relationship. As the “new Adam” (Rom. 5:12–21; 1 Cor. 15:22, 45–49), Jesus is the founder of a new people or race, who together make up his body. For Paul, Jesus himself is the embodiment of God’s distinctive holiness, i.e., God’s oneness, righteousness, grace, and loving mercy. The saints are those whose lives are set apart and sustained in relationship to this kind of holiness, and whose lives, in turn, bring those same qualities to expression.

“In Philippi” designates the physical, social, and cultural setting in which the Philippian Christians will “work out their’ salvation” (Phil. 2:12). In Paul’s day, Philippi was a flourishing Roman city, an administrative center of the Roman Empire and a crossroads of commerce, culture, and religion (Craddock, 12). It was also the site of an infamous battle fought there in 42 BCE between Brutus and Cassius, the assassins of Julius Caesar, and the victors, Antony and Octavian (Bakirtzis and Koester). A decade after this battle, Octavian defeated his former ally, Antony, and took for himself the title Caesar Augustus. He also rebuilt Philippi as a military outpost, established its leadership from the ranks of Roman soldiers and colonists, and granted the city the legal rights equivalent to a Roman territory in Italy. Citizens of Philippi were considered citizens of Rome itself (Bockmuehl, 4). Thus the city would have displayed all the trappings of Roman military power and presence, as well as shrines and altars dedicated to the mother goddess Cybele, Isis, and other local deities.

This is consistent with what Acts tells us of Paul’s ministry in Philippi. According to Acts 16:11–40, Paul’s missionary team encountered a slave girl whose “spirit of divination” was a source of income for her owners. After casting out the demon that possessed the girl, Paul and Silas are dragged before the magistrates, identified as Jews, and charged with disturbing the peace and advocating traditions that threaten Roman custom. This, Paul’s first recorded encounter with Roman judicial authority, leads to severe beating and imprisonment. Recent studies, moreover, suggest that Philippi, rather than Rome, may have been the place where Paul was eventually executed (Bakirtzis and Koester). Paul’s self-designation and call to slavery in conformity with Christ Jesus is even more provocative if we consider Paul’s history in the city along with the environs of the congregation—a city filled with the images of Roman domination.

Paul concludes the address to the Philippians with the phrase “with bishops and deacons,” which contemporary readers may associate with ecclesiastical offices. In Paul’s day, however, the structures of the church were not so well developed, and many scholars argue that official offices with designations such as these did not develop for another generation or two. At the time Paul wrote to the Philippians, the terms were in common use to designate overseers (the literal meaning of the Greek word translated as “bishop”) and attendants in civic or religious organizations, especially those who had responsibility for collecting and managing funds (Craddock, 13). Later in the letter Paul will thank the Philippians for their financial partnership in his mission (4:10–20), and in 2 Cor. 8–9 he lifts them up as a model of generosity amidst poverty and suffering. It is likely, then, that Paul is thinking of those among the Philippians who have had a hand in bringing this aspect of their partnership in ministry to fruition.

The greeting proper (1:2) with which Paul closes the introduction to this letter names two foundational aspects of Paul’s ministry—grace and peace through God in Jesus Christ. These terms may sound innocently religious and even bland in our ears, but in fact they were politically charged in Paul’s day. The Greek word “charein,” which meant something like “greetings,” was a common oral and literary greeting. Paul alters the customary greeting and introduces all of his letters with “charis” (grace), which reminds his audience of their fundamental dependence upon God’s grace. The word “peace,” also found in the greeting of most of Paul’s letters, recalls the Hebrew word “shalom,” which speaks of the peace of God that had been promised to Israel through the prophets. “Peace” was also commonly used in Paul’s day in reference to the benefits of the Roman Empire. Peace was the social ordering of life secured by Roman conquest. “Pax Romana,” the peace and security of Rome, was in fact the motto of the Roman world after Octavian (Caesar Augustus) ended the civil war and established “universal peace” (Georgi, Theocracy, 28; see also Horsley, and Wengst, Pax Romana). In Philippi as in Rome, the word peace was laden with the associations of imperial rule. This context makes it all the more striking that Paul greets the Philippians not by affirming the “Peace of Rome,” but by acknowledging the grace and peace that is from “God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.” Caesar is neither god nor father, despite the claims of Roman imperial propaganda. For Paul there is but one God and Father, the one he knows from the traditions of Israel and from his encounters with Jesus Christ.

Philippians 1:3-11: A Joyous Prayer of Thanksgiving

In the two introductory verses, Paul has already subtly introduced the key themes and images that will run throughout this letter. In the section that follows, 1:3–11, Paul offers thanksgiving for the Philippian Christians (which further evidences the deeply personal relationship he has with them), begins to speak of his and their current circumstances, and names the hope he has for them. With the exception of his correspondence with the Galatians, all of Paul’s letters include a thanksgiving. Thanksgivings were also found commonly in other letters of the day. Paul adapted the common form for his own purposes, using the thanksgiving to reestablish a favorable relationship with his audience, which would make hearers more attentive and receptive to his message, and to lay out the primary themes he addressed in the rest of the letter (Murphy-O’Connor, 62ff.).

Throughout the thanksgiving section in Philippians, Paul’s language breathes of joy, mutual affection, partnership, grace, and love—to all of which he later returns. He also mentions for the first time his imprisonment (1:7), which becomes the focus of the following section (1:12–26).

It would be a mistake, however, to reduce this thanksgiving to a “table of contents” or a rhetorical device designed to curry favor with his audience. At its most basic level, it is a heartfelt prayer that demonstrates Paul’s exuberance for the gospel and is driven by his strong eschatological convictions—his sense of the way God has transformed life, both present and future.

Paul twice refers to the “day of Christ” (1:6, 10) and seems to understand it as a time of completion and judgment. We need to be careful, however, not to limit Paul’s eschatological convictions to (future) temporal terms, or to speculate at length about whether he believed the world was about to end. Paul may indeed have believed that the final judgment was at hand, but if so, he believed it in large measure because of what God had already done and was now doing, both among the Philippians and through his own ministry. In other words, the world he had once known no longer held him captive; through God’s transformation it was already coming to an end. Appropriately, then, Paul’s thanksgiving focuses first on the past, remembering what God has done (1:3–6), then on the present (1:7–8), and finally on the future, Paul’s hope for the Philippians in the day of Christ (1:9–11) (Craddock, 16–21).

While this thanksgiving anticipates what is yet to come, Paul’s language immerses his audience in an extravagance of grace that transcends the human boundaries of time and place, testifying to his perception of how far God’s grace reaches into human experience: “constantly praying with joy in every one of my prayers for all of you” (1:4); “your sharing in the gospel from the first day until now” (1:5); “all of you share in God’s grace with me” (1:7); “I long for all of you with the compassion of Christ Jesus” (1:8); “that your love may overflow more and more” (1:9), all yielding “the harvest of righteousness, that comes through Jesus Christ for the glory and praise of God” (1:11). Because the past, present, and future are filled with God’s grace (“charis”), thanksgiving (“eu-charis-to”) is the appropriate response (1:3).

For Paul, God’s grace also embraces disconfirming experiences, such as his imprisonment (1:7). While we do not know where Paul is in prison—Rome, Caesarea, or Ephesus are most often mentioned as possibilities (Osiek, 27–30; Bockmuehl, 25–32)—it is clear that he is in Roman hands, which suggests that he was facing serious charges and possibly lethal consequences. Paul mentions in verse 13 that his imprisonment is “for Christ” and that, despite what some may think, his circumstances have led to the spreading the gospel and have made other brothers and sisters speak the word more boldly (1:12–14). Paul refers to the Philippians as “fellow sharers,” “co-partners,” or “co-fellowshippers,” emphasizing the depth of their relationship with him (Craddock, 19). When Paul speaks the language of “koinonia,” as in verses 5 and 7 (see also 2:1, 3:10, 4:14), he has something more in mind than the English translation “fellowship” has come to mean. He’s not thinking of moments of easygoing friendliness or a casual meal with other church members, but of a deeply committed, honest, and even pain-filled involvement with one another. In this case, partnership/fellowship between Paul and the Philippians implies their complete identification with the gospel of Jesus Christ and with Paul’s mission, whether that mission, or grace (as he calls it here), takes them with hi...