![]()

Chapter One

Did Jesus Intend to Found a Church?

Did Jesus intend to found the Christian church? This interesting question can be answered in the affirmative and in the negative. It depends on what precisely is being asked. If by church one means an organization and a people that stand outside of Israel, then the answer is no. If by a community of disciples committed to the restoration of Israel and the conversion and instruction of the Gentiles, then the answer is yes.1 So what exactly did Jesus found?

The word usually translated “church” in the Greek New Testament is ekklēsia. In the New Testament the word occurs some 114 times. But it also occurs some 100 times in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Most of the occurrences of ekklēsia in the Septuagint translate forms of qahal, whose basic meaning as a noun is “assembly” or “congregation” and as a verb is “to assemble.” The Christian word “church” comes from the Greek adjective, kyriakos, which means “of the Lord” or “the Lord’s” (cf. 1 Cor. 11:20, “the Lord’s supper”; Rev. 1:10, “on the Lord’s day”). Accordingly, “church” is an anglicized and abbreviated form of hē ekklēsia hē kyriakē, “the Lord’s assembly.”

The Language of Assembly in Jesus

The word ekklēsia occurs three times in the Gospels, all three in the Gospel of Matthew. After Peter identifies Jesus as the Messiah, Son of God, Jesus declares: “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church [ekklēsia], and the powers of death shall not prevail against it” (Matt. 16:18). Two chapters later, in the discourse on community discipline, Jesus instructs his disciples regarding one who has sinned and initially refuses to hear out the offended party: “If he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church [ekklēsia]; and if he refuses to listen even to the church [ekklēsia], let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector” (18:17).

How much of this material derives from Jesus and, assuming that some of it does, in what form Jesus originally uttered it—these matters are not easy to determine. The first part (Matt. 16:17–19), Jesus’ response to Peter’s confession, may have been added to the tradition that Matthew found in Mark 8:27–30. Then again, Mark 8:27–30 may represent an abridged version of a longer, fuller, more primitive version of the story. In favor of the latter view is the presence of a number of Semitisms, as well as vocabulary that Matthew does not use elsewhere.2 The second and third references to the “church,” in Matthew 18:17, are part of tradition (i.e., Matt. 18:15–17) that probably derives from Q (cf. Luke 17:3–4), a source preserving Jesus’ teachings, on which both evangelists Matthew and Luke drew.

At least it seems that Jesus envisioned and spoke of an assembly, or community, of disciples, who adhere to his teaching and embrace his mission. And I think what he envisioned was more than merely a band of disciples, such as gathered around several rabbis in his approximate time. Jesus’ assembly, his

qahal or

ekklēsia, was perhaps somewhat analogous to the

yahad (

yaad), or “community,” we hear about in some of the Qumran scrolls. In the scrolls, which are sometimes dubbed “sectarian,” in the sense that they were composed by the men of Qumran (probably to be identified with the Essene sect), we encounter dozens of references to the community. These men are said to constitute the “community of God” (1QS 1.12), a “community whose essence is truth, genuine humility, love of charity, and righteous intent” (1QS 2.24), and the like. This community was guided by the prophetic command of Isaiah 40:3, “In the wilderness prepare the way of the L

ORD …” (1QS 8.13–14). Indeed, just like the early Christian movement, the men of Qumran called their movement “the Way” (1QS 9.17–18; 10.21; cf. Acts 9:2; 19:9, 23; 22:4; 24:14, 22), an unmistakable allusion to the passage from Isaiah. The Qumran community also called itself a

qahal, or “assembly” or “congregation,” many times in the

Damascus Covenant (=

Damascus Document [CD] 7.16–17; 12.5–6; 14.17–18), the

War Scroll (1QM 4.10; 14.5), and other sectarian texts (e.g., 1QSa 1.4, 25; 2.4). If the Hebrew scrolls from Qumran had been translated into Greek, it is probable that the occurrences of

qahal would have appeared as

ekklēsia.

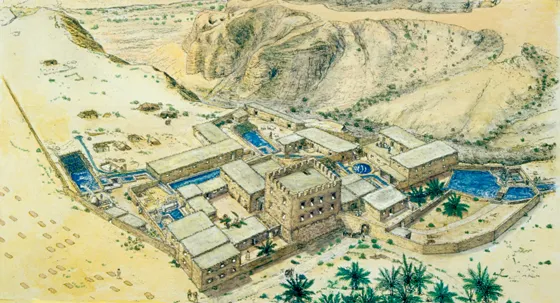

Figure 1.1. Community Compound at Wadi Qumran. The ruins at Wadi Qumran, west of the Dead Sea, were excavated in the 1950s by Roland de Vaux. Further work in the 1990s under the direction James F. Strange resulted in the discovery of an ostracon (a potsherd that bears writing) on which property (given to the Qumran community?) is listed. Pictured above is an artistic reconstruction of the community compound. Courtesy of Israelphotoarchiv©Alexander Schick bibelausstellung.de.

Qumran’s community was organized. There was a Righteous Teacher, whose instruction was authoritative (CD 1.11; 20.14, 28, 32; 1QpHab 1.13; 7.4; 4Q165 frags. 1–2, line 3). There was a group of “twelve” men (nonpriests), who were important in the Yahad (1QS 8.1; 4Q259 2.9), as well as twelve “commanders” (4Q471 frag. 1, line 4) and twelve ruling priests (1QM 2.1; 4Q471 frag. 1, line 2). The twelve tribes/sons of Israel are frequently mentioned (1QM 3.14; 5.1; 4Q365 frag. 12b, 3.12; 11Q19 21.2–3; 23.3, 7; 11Q20 6.11). All of this has a counterpart in the Jesus circle: Jesus appoints twelve men, whom he calls apostles (Matt. 10:2; Mark 3:14; Luke 6:13); he speaks of the twelve sitting “on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Matt. 19:28 = Luke 22:28–30). More will be said below about the importance of the twelve typology.

Qumran speculated about the seating arrangements when the Messiah appeared. They believed they knew who would sit with the Messiah and what types of persons would be excluded from this exalted company (e.g., the lame, blind, and persons with other physical defects; cf. 1QSa 2.3–9). The disciples of Jesus bickered over who would sit in the places of honor (Matt. 20:20–28; Mark 10:35–45; Luke 22:24–27) and Jesus himself, in his well-known parable of the Banquet (Luke 14:15–24, esp. v. 21), implied that the lame, blind, and physically defective in fact would sit in the places of honor.

The coherence of community and organizational language is remarkable, to be sure, but it does not require us to think that Jesus “got his ideas from Qumran” or that he had at one time been an Essene. It shows that Jesus and the men of Qumran belong to the same culture but not to the same community. The coherence also reveals the presence of traces of community, even community structure, in the Jesus circle prior to Easter and the launch of the church.

We see no radical, non-Jewish changes in the organization of the Jesus movement in its early years. In the book of Acts (at 6:1–6), the appointment of deacons (from the Greek diakonein, “to serve”) to assist the apostles is completely in step with Jewish culture. The continuity with Jewish traditions of community and social organization is reflected in the language of Paul, Peter, James, and others, as we shall see in the following sections.

The Language of Assembly in Paul

The word ekklēsia, in reference to the Christian assembly, occurs many times in the book of Acts and many times in Paul’s Letters. In his letter to the Christians in Rome, Paul speaks of “the churches of the Gentiles” (Rom. 16:4) and “the churches of Christ” (16:16). In his letters to the Christians of Corinth, the address reads: “To the church of God which is at Corinth” (1 Cor. 1:2; 2 Cor. 1:1); also in his Letter to the Galatians: “To the churches of Galatia” (1:2); and in the Thessalonian correspondence: “To the church of the Thessalonians” (1 Thess. 1:1; 2 Thess. 1:1). Eleven of the thirteen letters that bear the name of Paul as sender refer to the church, the ekklēsia, with some 60 or 61 occurrences in all, or just over half of all occurrences of the word in the writings of the New Testament. Indeed, most of the 23 occurrences of ekklēsia in the book of Acts involve the missionary activities of Paul. From these data we may justly infer that the language and concept of the church were of major importance to Paul, the apostle to the Gentiles.

The nominal and verbal forms of qahal occur some 65 times in the Dead Sea Scrolls. One occurrence offers a striking parallel with Paul’s usage. In the War Scroll some banners are to have inscribed on them the words “The Assembly of God [qahal ’el]” (1QM 4.10). In Greek this would be rendered ekklēsia tou theou, that is, “assembly/church of God.” Comparison of Paul’s ecclesiastical or organizational language with the scrolls from Qumran reveals several interesting parallel points. Paul speaks of actions taken “by the many [hypo tōn pleionōn]” (2 Cor. 2:5–6), which approximates references to the “many” or “general membership” in the Community Rule (e.g., 1QS 6.11b–12, “During the session of the general membership [harabim] no man should say anything except by the permission of the general membership [harabim]”). In Philippians 1:1 Paul mentions “bishops” or “overseers” (episkopoi), which has its equivalent in the very passage in the Community Rule that has just been mentioned: “… who is the overseer [hamebaqqer] of the general membership [harabim]” (1QS 6.12). The Hebrew’s mebaqqer appears to be the equivalent of Paul’s episkopos.

There are also several important theological parallels between Paul’s language and the language of the Scrolls. Paul speaks of the “righteousness of God” (Rom. 1:17; 3:21:

hē dikaiosynē theou); so do the Scrolls (1QS 1.21; 10.23:

tsedekot’el; 1QS 10.25; 11.12:

tsedeket ’el). Paul speaks of the “grace of God” (Rom. 5:15; 1 Cor. 3:10:

hē charis tou theou); so do the Scrolls (1QS 11.12,

hasdei ’el). Paul also speaks of the “works of the Law” (Rom. 3:20, 28; Gal. 2:16; 3:2, 5, 10:

erga nomou); so do the Scrolls (1QS 6.18,

ma’esey betorah; 4Q398 frags. 14–17, 2.3 = 4Q399 frag. 1, 1.11:

ma‘esey hatorah). And Paul speaks of the “new covenant” (2 Cor. 3:6,

kainē diathekē); so do the Scrolls (CD 19.33–34; 20.12; 1QpHab 2.3:

berith haadashah).

3From this brief survey we see that Paul’s ecclesiastical language is indebted not to some foreign Hellenistic terminology but to the language of his people—the Jewish people, a language that is reflected in some cases in the old Scriptures and in other cases in the more or less contemporary writings from Qumran. The use of ekklēsia in the Septuagint, Philo, Josephus, and various writings from the New Testament period (e.g., Jdt. 6:16; 7:29; T. Job 32:8; Pss. Sol. 10:6) bears this out.

The use of the word “church” and related terminology by the early followers of Jesus gives no indication that this new community thought of itself as standing outside of Israel. But the preference for and repeated use of “church” (ekklēsia), instead of “synagogue” (synagōgē), make clear that the assemblies of Christians—almost always made up of Jews and Gentiles—normally functioned outside the established synagogues. This seems clear in Paul’s Letters and in the narratives of his missionary travels and activities recounted in the book of Acts.

The Language of Assembly in Peter and James

The language and orientation of the Letters of Peter and James, however, are noticeably different from what we have seen in Paul. Although I cannot here debate questions of date and authorship of these letters, I take the position that both James and 1 Peter are authentic and early letters, the former dating to the late 40s or early 50s, and the latter dating to the early 60s. Both letters reflect an unmistakably Jewish, Palestinian flavor, even if the latter, that is, the Letter of Peter, was composed in or near Rome.

First Peter is addressed “to the exiles of the Dispersion” (or “Diaspora”), who are “chosen and destined by God the Father and sanctified by the Spirit” (1 Pet. 1:1–2a). Such language is right at home in the world of Jewish thought and self-understanding. The word “exile” (also “alien” or “sojourner”) is parepidēmos, that is, the foreigner who resides alongside a people not one’s own. In the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, the great patriarch Abraham applies this term to himself when he says, “I am a resident alien and a sojourner [paroikos kai parepidēmos] among you” (Gen. 23:4 AT). The psalmist alludes to this passage and to the history of the great patriarchs, all of whom were sojourners, when he cries out to God in prayer: “Listen to my prayer, O Lord, and to my petition give ear; do not pass by my tears in silence, because I am a sojourner [paroikos] with you, and a visiting stranger [parepidēmos], like all my fathers” (Ps. 38:13 LXX, NETS = 39:12 RSV).

Peter also describes his readers, his fellow aliens, as “of the Dispersion,” or “Diaspora.” The Greek word diaspora occurs about one dozen times in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, including occurrences in some books of the Apocrypha that may have originated in the Greek language. Scripture reassures the people of Israel that the scattered will be gathered: “If your dispersion be from an end of the sky to an end of the sky, from there the LORD your God will gather you” (Deut. 30:4 AT; Neh. 1:9; Ps. 147:2). The prophet Jeremiah warned a sinful and disobedient people: “Send them away from my presence and let them go! … I will disperse them in a dispersion in the gates of my people” (Jer. 15:1, 7 AT). But a forgiving God promises to restore “the tribes of Jacob and to turn back the dispersion of Israel” (Isa. 49:6 AT). This same hope is expressed in the struggle against Antiochus IV, where we hear the prayer: “Gather together our scattered people, set free those who are slaves among the Gentiles [nations], look on those who are rejected and despised, and let the Gentiles [nations] know that you are our God” (2 Macc. 1:27). Thus also prays the author of the Psalms of Solomon: “Gather together the dispersion of Israel with pity and kindness, for your faithfulness is with us” (8:28).

Peter’s description of his addressees as “exiles of the dispersion” would immediately bring to the minds of his readers and hearers—most of whom we should assume were Jewish—these themes and images expressed in Israel’s sacred writings. Just as surely as the patriarchs long ago were dispersed among the nations, away from the land promised by God, living as exiles and sojourners, so those who hope in Jesus the Messiah are scattered about in the districts of Asia Minor, far away from the land of Israel. Implicit in this typology is the hope, expressed in the prophets, that someday God will gather his scattered people.

The Judaic character of the Letter of James is quite evident. The letter beg...