- 538 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sharp Cut by Steven H. Gale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatur & Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Servant

RELEASED: Venice Film Festival, September 3, 1963; American premiere, New York Film Festival, September 16, 1963; British premiere, London, November 14, 1963

SOURCE: The Servant, by Robin (Sir Robert) Maugham; novel (1948)

AWARDS: British Screenwriters Guild Award (1964); New York Film Critics Best Writing Award (1964); New York Times listing, one of the ten best films of the year; Silver Ribbon (Nastro d’argento) for Best Foreign Film, Italy (1966); Las Jornadas Internacionales de Cine (Spain), Castillo de Plata Cine Club, Irun. Also won British Academy Awards for Best British Actor (Bogarde) and for Best Black and White Cinematography. Other nominations included British Academy Award for Best Film and Best British Film; New York Film Critics Circle Awards for Best Actor (Bogarde), Best Direction, and Best Film.

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Landau/Springbok-Elstree; released by Warner-Pathe

DIRECTOR: Joseph Losey

EDITOR: Reginald Mills

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Douglas Slocombe

PRODUCERS: Joseph Losey and Norman Priggen

PRODUCTION DESIGN: Richard MacDonald

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Ted Clements

MUSIC COMPOSER AND CONDUCTOR: John Dankworth

COSTUME DESIGNER: Beatrice Dawson

CAST: Dirk Bogarde (Hugo Barrett), James Fox (Tony), Sarah Miles (Vera), Wendy Craig (Susan Stewart), Derek Tansley (Head Waiter), Dorothy Bromily (Girl in Phone Box), Ann Firbank (Society Woman), Harold Pinter (Society Man), Patrick Magee (Bishop), Alun Owen (Curate), Doris Knox (Older Woman), Jill Melford (Younger Woman), Richard Vernon (Lord Mountset), Catherine Lacey (Lady Mountset), Chris Williams (Cashier in Coffee Bar), Brian Phelan (Man in Pub), Alison Subohm (Girl in Pub), Hazel Terry (Woman in Bedroom), Philippa Hare (Girl in Bedroom), Gerry Duggan (Waiter)

RUNNING TIME: 115 minutes1

BLACK AND WHITE

RATING: Not rated

VIDEO: Thorne EMI

ROBIN (SIR ROBERT) MAUGHAM’S 1948 novella The Servant was the source for Pinter’s first movie script. Pinter wrote a screen version of The Servant, intending it for Michael Anderson; he rewrote it almost completely when Losey decided to do the film.2 Losey had seen the Armchair Theatre television broadcast of A Night Out and wrote to Pinter to express his admiration.3 Starring Dirk Bogarde as the servant Hugo Barrett, the movie, Britain’s entry at the Venice Film Festival and later at the first New York Film Festival, opened in London in November of 1963.4 Besides The Servant, the British entries for the Venice Festival were Tom Jones and Billy Liar (Francesco Rosi’s Mani sulla citta won the Golden Lion). In spite of being an official entrant, the film languished in the can and even in England was considered unreleasable. It was actually withheld by the producers, Associated British Pathe (ABP), from the London Film Festival, despite the festival organizers’ invitation. Then Richard Roud requested that the film be included in the New York Film Festival in September. This event seemed to be the key, and critical reception when the movie opened in London on November 14 was full of lavish praise.

In his interview with Bensky for the Paris Review, the scenarist reveals the novella’s source of appeal to him when discussing the repeated theme of dominance and subservience in his plays and its particular application to his short story “The Examination” as a question of “Who was dominant at what point”: “That’s something of what attracted me to do the screenplay of The Servant… [the] battle for positions” (362–63). The early confrontation between Tony and Barrett in which Tony invites his prospective servant to sit down is the first indication of this theme, for by forcing the other man to take a seat, Tony temporarily enjoys a one-up position. This seating game appears in several early Pinter dramas (notably The Room and The Birthday Party) as a means of demonstrating dominance.

Only fifty-five pages in length, the story is narrated by one Richard Merton, who details the moral corruption of his friend Tony during the first two years after World War II. Recently demobilized after five years’ service in the Orient, Tony moves into an apartment with his manservant Barrett and Barrett’s niece, Vera, who is to work as a maid. Tony’s girlfriend, Sally Grant, starts to worry about Barrett’s influence on Tony, and the theme is set. Like Tony’s ex-nanny, Barrett “insulates” him “from a cold drab world” (Maugham, 31) to the extent that he eventually rejects Sally, Merton, his other friends, and his work, even though he has discovered that Vera was Barrett’s mistress, brought along to seduce her employer.

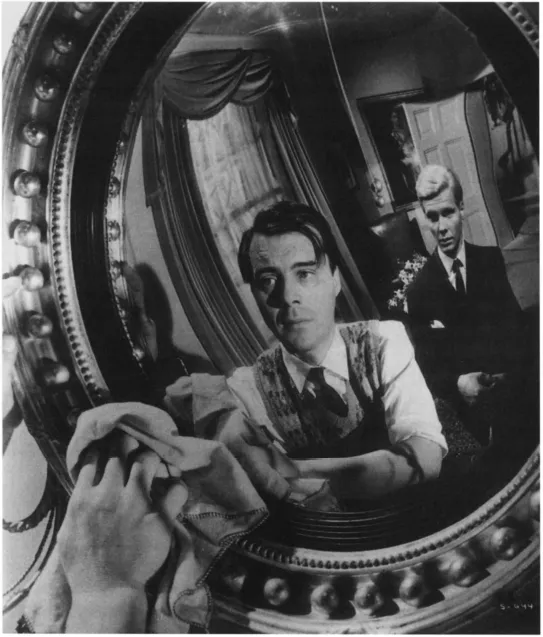

The Servant (1963). Dirk Bogarde as the manservant Barrett and James Fox as Tony. Avco Embassy Pictures. Jerry Ohlinger Archives.

Pinter improved the product as a film. The narrator is discarded, and a secondary conflict grows out of the fiancée’s relationship with the manservant, although the fundamental theme of the movie is domination as related to the male characters. Barrett appears infrequently in the novel and often only at second hand when he is mentioned in someone’s gossip. He is seldom seen in person. As a matter of fact, he is not even introduced until nearly one-sixth of the way into the book, and when he is presented, it is clear from Tony’s remark, “I’ve given up trying to control him,” that the servant dominates his master easily from the beginning (Maugham, 16). There is no sense of conflict between the two men and no tracing of the breakdown of Tony’s character. This is because of Maugham’s conception of Barrett’s nature; like John Keats’s Lamia, Barrett, who is described as a snake, is fundamentally evil. Tony is “lazy, and he likes to be comfortable,” according to the narrator, so Barrett’s method is simple: “He’s found out Tony’s weakness, and he’s playing on it” (20). The basic difference between the novelist’s approach and Pinter’s is that in the first instance a tale is told, simply and briefly recounting something that has happened, whereas the scenarist demonstrates the events taking place, leading his audience to a psychological understanding of not only what has happened but also why it has happened. Maugham’s work is less imaginative.

In the novel, Sally is a minor character; in the movie, with her name changed to Susan Stewart (acted by Wendy Craig) and incorporating Merton’s role and point of view, she becomes the principal force trying to undermine Barrett’s unhealthy influence. She fails, however, and by the conclusion, there has been a role switch between Tony (James Fox) and his servant à la Pinter’s A Slight Ache, “The Examination,” and The Basement. The latent homosexuality of the book is toned down, too, making it more ambiguous and thereby emphasizing the theme of domination.5 In the novel the obscuring of the homosexual element is accomplished by having the narrator return to Tony’s flat in a final attempt to woo him away from Barrett, only to find that the servant has introduced another girl into the household to entertain his master and himself; in the movie it is Susan who makes the last attempt, arriving at Tony’s in the midst of an orgy. She tries to arouse Tony into realizing the situation by ridiculing Barrett, but Tony is incapable of breaking his servant’s hold on him, and the kiss serves more tellingly to demonstrate the reversal of roles that has taken place.

There are additional minor differences between Maugham’s original and Pinter’s adaptation, including the move of the apartment from the basement, the inclusion of the ball game on the stairs and the army comradeship talk between Tony and his manservant, the fact that Tony rather than Merton discovers Barrett and Vera together in the film, and Vera’s rejoining the two men in the film instead of turning to prostitution. Basically, though, the changes that Pinter makes grow out of his attitude toward the material contained in Maugham’s story. The novel has a marked sense of a morality play, with the characters obviously representing several of the deadly sins. Everything is clear-cut and almost preordained, because Barrett is equated with evil. Thus, Vera represents lust, her father stands for avarice, and Tony symbolizes the love of comfort and ease, a combination of sloth and gluttony. When Pinter turns these elements into a psychological study, the tale becomes interesting and moving.

Discussing the alterations that he effected, Pinter says, “I followed it [the novel] up. I think I did change it in a number of ways. I cut out the particular, a narrator in fact, which I didn’t think was very valuable to a film, but I think I did change it quite a lot in one way or another, but I kept to the main core at the same time the end is not quite the same ending that it was in the book. I must have carte blanche you know, to explore it.”6

In fact, Losey was attracted to the script (for which Pinter received £3,000) because of scenes not in the novel—Barrett’s rehiring, the final party, and so on—but he was also actively engaged in the rewriting of the script.7 He noted that Pinter had “already written a screenplay which I thought was 75 percent bad and unproducible, but had a number of scenes which were not changed as they reached the screen. I gave him a very long list of rewrites which enraged him, and we had an almost disastrous first session. He said he was not accustomed to being worked with this way—neither was I, for that matter—but he came to see me the next day, I tore up the notes, and we started through the script” (Milne, Losey on Losey, 152).

The changes and additions give Pinter some flexibility to pursue his characteristic interests. The Pinter brand of humor and dialogue both appear in the film (including, incidentally, a scene in a French restaurant that features Pinter and Patrick Magee and Alun Owen, colleagues from the Ian McMaster repertory tour days, in bit parts). The confused, meaningless, yet funny social small talk that the author captures so well in demonstrating the lack of communication between people is evident in Tony’s meeting with Susan’s parents, Lord and Lady Mountset:

LADY MOUNTSET. That’s where the Ponchos are, of course, on the plains.

SUSAN. Ponchos?

LORD MOUNTSET. South American cowboys.

SUSAN. Are they called Ponchos?

LORD MOUNTSET. They were in my day.

SUSAN. Aren’t they those things they wear? You know, with the slit in the middle for the head to go through?

LORD MOUNTSET. What do you mean?

SUSAN. Well, you know … hanging down in front and behind … the cowboy.

LADY MOUNTSET. They’re called cloaks, dear.8

In addition, as pointed out by John Russell Taylor, “Tony’s house is a sophisticated upper-class extension of the recurrent symbol in Pinter’s early plays, the room-womb which offers a measure of security in an insecure world, an area of light in the surrounding darkness. But here the security is a trap sprung on the occupant by his own promptings and by the servant who embodies them and knows too well how to exploit them” (“Guest,” 38–39).9 The film, then, fits into Pinter’s artistic development perfectly, coming between A Slight Ache and The Lover, for in his writing for the theatre at this time, the playwright was beginning to shift his attention from examining the disintegration of individuals in the presence of outside, physical menace to exploring the interior, psychological source of that menace.

Considering that The Servant was the author’s first attempt at screenwriting, the result is especially impressive. Both thematically and stylistically, the film is clearly related to the comedies of menace that he had been writing for the stage since 1957. It also contains many of the elements that appeared in the movie scripts that he wrote over the next several years—a black-and-white film, adapted from a novel (a novella, really), directed by Losey, focusing on the concept of domination, and liberally sprinkled with humorous Pinteresque dialogue. An examination of the opening and closing sequences of the film illustrates how the screenwriter used Maugham’s morality tale as his source but turned it into a unique piece of art when translating the prose to a cinematic medium.10

Chapter 1 in the novel provides the exposition and introduces the characters. While not much is revealed about the narrator, who has joined a publishing firm, it is clear that he and Tony are from the same social class. An orphan, Tony had left Cambridge, where he was reading law, and joined Merton’s regiment in August 1939; his joining the regiment as a trooper was an indication of his democratic nature, which came through in spite of his upper-class upbringing. The last time that the two men had seen each other was five years previous to the beginning of the story—Tony had just received orders transferring him from their tank brigade to a post in the Far East. His disappointment at the separation from the regiment, which “had taken the place of a family in his life,” was evident: “he was standing in the desert with his head tilted defiantly to the sky and his eyes full of tears” (Maugham, 9).

Prior to their reunion, this sketchy outline of Tony’s background, combined with his jesting on the telephone when the two men first reestablish contact, is all that is revealed about him to depict his character. A rough physical picture is provided when Merton sits in the bathroom while Tony bathes in the tub in his flat on Ebury Street, but it is only when Tony mentions Sally that he takes on a personality for the rest of the chapter. Merton explains how excited Tony is to have returned to London after a five-year absence, comments on Sally’s love for him, and describes the finding of a house for Tony. The chapter concludes with Tony’s complaint that his “daily,” the housekeeper, cannot cook and the narrator’s suggestion that he employ a manservant.

The concluding chapter of the novel finds the narrator making a final visit to Tony’s house, as Susan does in the movie, in a desperate last attempt to save him from Barrett’s Svengali-like influence. Tony is lost, though, and not simply to a “plain love of comfort” (Maugham, 60). Merton accuses Barrett of destroying his victims “from within”: “He helps them destroy themselves by serving their particular weakness.” Thus, the double meaning of the book’s title becomes evident. Vera, Barrett’s “niece”/mistress, has succumbed to lust, Merton claims, and her father to avarice. Yet, Tony is even more completely damned, for, as soon becomes apparent, it is not just the love of comfort that has led to the dissipation and dissolution of his character. When the young girl arrives, it is clear that his very moral fiber has been corrupted by his indulging in illicit and perverting pleasures of the flesh. Early on Tony had asserted that he could get rid of Barrett anytime that he wanted to (31); by the end of the novel it is obvious that he can no more forgo Barrett’s services than an addict can reject the source of the addiction.

When Pinter adapted Maugham’s novel to the screen, he altered its thematic emphasis subtly and therefore was forced to adjust the presentation of the story as well. The film The Servant is not the novel The Servant—and it is better. The focus on Barrett as a corrupting power gives the tale more depth and significance than the simpler morality tale of the degeneration of Tony’s character under the influence of Barrett. All that Pinter does in the film script is designed to develop these points, but the twist that compounds the significance of the work is the gro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chronology

- Introduction

- Critical Analyses

- Appendixes

- Notes

- Bibliography: Works Cited

- Selected Bibliography

- Index