eBook - ePub

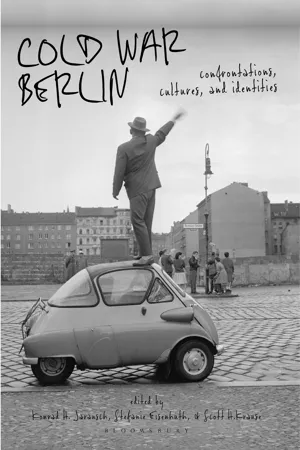

Cold War Berlin

Confrontations, Cultures, and Identities

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cold War Berlin

Confrontations, Cultures, and Identities

About this book

A wide range of transatlantic contributors addresses Berlin as a global focal point of the Cold War, and also assess the geopolitical peculiarity of the city and how citizens dealt with it in everyday life. They explore not just the implications of division, but also the continuing entanglements and mutual perceptions which resulted from Berlin's unique status. An essential contribution to the study of Berlin in the 20th century, and the effects - global and local - of the Cold War on a city.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cold War Berlin by Scott H. Krause, Stefanie Eisenhuth, Konrad H. Jarausch, Scott H. Krause,Stefanie Eisenhuth,Konrad H. Jarausch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & German History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Locating Berlin in the Cold War

1

From Heart of Darkness to Heap of Rubble: Berlin as Nazi Capital

Ciphers, Sceneries, and Analyses

Of course it had to be the Brandenburg Gate. Hastily summoned local SA units marched through this gate with great fanfare as soon as night had fallen on the day of Adolph Hitler’s appointment as Reich Chancellor heading a “Cabinet of National Unity.” The NSDAP apparently held special license for their march as the gate had been declared off limits for political demonstrations in the wake of the 1918/1919 Revolution. Whereas the media showed much interest in the novel spectacle, the reactions of passersby and residents were anything but uniform. While Jewish painter Max Liebermann colorfully denounced the columns passing his house, other witnesses appeared more curious than excited.

Image 1 Photograph by Georg Pahl.

The SA men—drunk on more than just victory—had to weave their way through the onlookers, while the billowing torches obscured visibility. January 30, 1933, must have been a typical Berlin winter day. Gloomy and cold. Anything but ideal conditions for the press photographers. Accordingly, the few pictures that were taken are hardly impressive. For this reason, the SA reenacted the torch march the following summer in order to create better images of an event that, at this point, had already been elevated to the status of national revolution—and celebrated as a public holiday.1

These staged celebrations illustrate the significance of Berlin as a symbolically charged site of politics and power. Even though Munich remained the “capital of the movement,” Nuremberg was being developed into the “city of the Reich party rallies,” and Adolph Hitler often resided at the Berghof in Berchtesgaden as well as—after 1941—at the Wolf’s Lair outside Rastenburg in East Prussia, Berlin proudly stood as an initiative of the party and subsequently transformed substantially. In 1945, Hitler deliberately chose to end his life here, but not before ensuring the city’s destruction. Accordingly, studies on national socialism have referenced “Berlin” more frequently than they have any other German city in their indexes of places. However, the city has often been viewed as a cipher: from this perspective, the capital has stood (and stands) not only as a site of macro-political decisions, but also for the heart of darkness. Day-to-day developments in Berlin—especially before the war—have long been neglected.

By contrast, this chapter aims to sketch a more differentiated image of the local developments, amid the tension between outward perceptions and inward changes, and to shed light on select facets of Berlin’s history.2 Without claiming completeness, this chapter outlines the role of the capital of the Reich (Reichshauptstadt) as a symbolical locale and seat of government. In spite of all propaganda, the city was by no means a uniform structure. This tension will be highlighted in the second section of the chapter. Because of the Nazi era’s significant impact on the postwar cityscape, this chapter will likewise investigate the role of Berlin as one of the most important armories of the Wehrmacht and shine a spotlight on the war within the city. A final section will sketch the city on the brink of the abyss that turned it “into the heap of rubble near Potsdam,” as the writer Berthold Brecht famously quipped once.

A Staged Capital

Not only was Berlin by far the largest city of the Reich, and the capital of what was by far the largest state within the Reich—Prussia—it also had been the capital of the German Reich since 1871. While the city only received the honorific “Reich capital (Reichshauptstadt)” moniker in 1933, both Reich and Prussian bureaucracies had long established their headquarters there. Numerous foreign embassies, missions, special interest groups, organizations, and unions had followed suit. Not surprisingly, Reichswehr and later Wehrmacht and SS also showed their presence, particularly in the political center. There were and are thousands of streets named Wilhelmstraße in Germany, but only in Berlin was Wilhelmstraße much more than a postal address: “It has happened. We are seated in the Wilhelmstraße,” noted Joseph Goebbles in his diary on January 31, 1933.3 Until 1945, Wilhelmstraße was used as a matter of course as a metonym for the Reich’s government. For this reason, the legal proceedings against twenty-one high-ranking officials of the German ministries in Nuremberg in 1947/49 were known as the Wilhelmstraße Trial.4 After parliament in Tiergarten had demoted itself to an organ of acclamation in the wake of the Reichstag burning in 1933, Wilhelmstraße served as the nerve center for the national socialist regime. The most important ministries of the Reich, from the office of the Reich Chancellor and the Reich President’s palace, to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, were located on this street. In 1936, the national socialists added Göring’s Reich Ministry of Aviation, which notably had emerged in part on the grounds of the former Prussian Ministry of War. Likewise, when the political—and racist—persecution apparatus was centralized in the form of the Reich Security Head Office of the SS (RSHA) in 1939, it was established just down the street.5

In 1943, author Ernst Friedrich Werner-Rades summarized the meaning of the “capital of the Reich” in a richly illustrated volume with the pathos so typical of the Nazis: “Berlin has, according to the Führer’s will, the duty and the calling to be example and epitome of the Reich, illustration and inspiration of the greater German life, not a gargantuan assembly of people in the Brandenburg March, but the appointed capital of Greater Germany, worthy of its calling.”6 However, Werner-Rades continues, only “after the end of the war, will representative buildings herald that Berlin has become […] within and without, the true capital of the Third Reich.”7 Indeed, the widespread architectural development of the city was, above all, a promise for the future. Very little was realized, if one does not take into account the area-wide demolition of a whole city district for the planned north–south axis and the entailed compulsory relocation of Berlin Jews, an act that paved the way for their deportations from October 1941 on.8

Wilhelmstraße served not only as the site of political decisions and their bureaucratic implementation, it was also a workplace and meeting point for the ministries’ staff. An analysis of the biographies of the Wannsee Conference participants shows very clearly, for example, that they already had encountered one another to some extent long before January 20, 1942. Nearly all of them lived in the genteel southwest of Berlin, and some were also members of those gentlemen’s clubs that also served as “nodes” for the networks of the higher office functionaries of Wilhelmstraße. Others knew one another through the Prussian State Council and the Council of Ministers for the Defense of the Reich, and had met in the Academy for German Law or in the lobbies of the Reichstag.9

Cultural life might have been quickly reduced to NS standards after the ousting of detested, defiant, and/or Jewish artists. But Berlin remained a tourist attraction thanks to its cultural infrastructure, numerous PR campaigns, fairs, and large-scale events.10 In 1938, the year of the annexation of Austria and the pogrom, visitors to Berlin already numbered more than 1.9 million, among them over 260,000 foreigners.11 New localities of national socialist stagings of power complemented the old attractions for these visitors. They might have even cheered on the Changing of the Guards, a goose-stepping ceremony reinstated after 1933.12 Berlin kept a peaceful front well into the war, while cities in the West of the Reich already experienced aerial bombardments. The regime’s entertainment movies vetted by Joseph Goebbels cannily presented the capital as a place of longing, as “Zwei in einer grossen Stadt” (“two in a big city”) of 1942 attests.13 Likewise, the Deutsche Wochenschau newsreel showcased Berlin time and again. Thus, even though Western allied air power had long smashed German air defenses, a summer 1944 episode on the “5th German Soccer War Cup” finals sought to demonstrate that urban life went on in spite of blackouts and bombings.14

Goebbels played a key role in staging and marketing the capital. Since 1926, Goebbels had not only been Gauleiter, or district leader, of Berlin, i.e., the highest local representative of the NS movement, but was also appointed Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda in mid-March 1933. Although an affair in the late 1930s would cause his star to temporarily wane with Hitler, and even though the office of General Building Inspector broadened Albert Speer’s power in the city, the small man from the Rhineland could command the entire party and propaganda machine at any time. In Berlin, Goebbels was master of the Blockwarte or block wardens, and the storm troopers and city government, and had furthermore requested, and received, as a contemporary comment emphasizes, in the “Statute of the Constitution and Administration of the Reich Capital Berlin” “considerably further reaching authority than usual.”15 Even before a legal process had been established in April 1933, the national socialist city commissioner (and later city president) Julius Lippert, appointed by Goebbels, started a large political and racist reshuffling of personnel. Accordingly, far more employees were dismissed in Berlin than in most of the other cities in the Reich—and frequently replaced by national socialists.16 Very quickly, the cronyism got out of hand, so that even Goebbels had to admit in his diary that he was presiding over the “Berlin district’s stables of corruption.”17

This notwithstanding, Goebbels staged the Labor Day parades (beginning in 1933) as well as the Olympic Summer Games (1936), the visit of Benito Mussolini (1937), and the celebrations for Hitler’s fiftieth birthday (1939), during which a whole boulevard—today’s Strasse des 17. Juni bisecting Tiergarten—was dedicated to the man being celebrated.18 Naturally, the parade of the Berlin garrison, as depicted in the Wochenschau, led through the Brandenburg Gate after the campaign against France in July 1940, and was accordingly received as the German victory parade.19 In this spirit, Goebbels orchestrated his speech in the Berlin Sportpalast on February 18, 1943, to declare “‘total war.” As a matter of fact, the Gauleiter spoke at a district event in front of hand-picked guests. That he spoke in Berlin, however, gave him claim to a more extensive prominence across the Reich—and the capacity to conceal the fact that Hitler could not be convinced to speak in public following the defeat of Stalingrad.20

Stagings of that kind were, of course, always intended to appeal to both the Germans not living in the capital, and to foreign nations. Berlin was, after all, the focus of the world. Contrary to the German reporters, foreign journalists were not bound by the orders of the Ministry for Propaganda, but they suffered from lack of information and were punished directly as well, for example, by revoking their accreditations.21 Yet, the anonymity of the metropolis shielded informal conversations with state and party functionaries, as well as meetings with German journalists and other informants. In the bars on the Kurfürstendamm or at the Zoo Gardens, in clubs, organizations, and at receptions, they were able to get their hands on further intelligence in addition to any official announcements, albeit in restricted fashion. If, for instance, there were any accounts at all of act...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Introducing Cold War Berlin

- Part 1: Locating Berlin in the Cold War

- Part 2: Disjointed and Resilient Local Entanglements in the Cold War

- Part 3: Berlin’s Memory Culture

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- Imprint