![]()

CHAPTER 1

Authorial networks

If ephemera are often defined as ‘authorless’,1 fashion ephemera seem to have too many authors. From their creation to their archiving in museums, fashion ephemera enter into contact with multiple figures, who play, in very different ways, an authorial role in relation to them. In fact, the invitations, catalogues and press releases conserved at MoMu lie on a contested terrain, having the capacity to make and reveal complex authorial networks involving both their creation and their subsequent histories. Yet these ephemera have generally been identified simply by the names of the fashion designers who produce them or used as self-explanatory evidence of the fashion designers’ collaborations with graphic designers or famous photographers. Nothing has been written to explore what type of authorial discourses these ephemera create, and how they proliferate through their peculiar textual, visual and material features.

Drawing on works on authorship, but also on auteur theory, critical theory, agency studies and novels discussing the role of authors and authorship, this chapter stresses how fashion ephemera are instrumental in understanding how authorship and authors are central, dynamic, complex and mutable notions in fashion. Fashion ephemera unveil many fashion actors (not only designers) and institutions which are building, through ephemera, discourses about issues of creation, creative processes, making, aesthetic encounters, power relations and the creation of value in fashion. Fashion ephemera have the capacity to generate and re-animate these discourses, manifesting how ideas of authors and authorship are strategically celebrated, problematized, denied, hidden and negotiated through the material, visual and textual features of ephemera.

Matters of signature: From authenticity to intimacy

From a museological point of view, the name of the fashion designer is what assigns value to all MoMu ephemera. Typed with a specific font or even handwritten on the surface of the ephemera, the name evokes a direct relation with the fashion designer. The name serves to consecrate the value of these ephemera, although these objects are not physically created directly by him or her.2 In their ‘Le Couturier et sa Griffe: Contribution à une Théorie de la Magie’ (1975), Pierre Bourdieu and Yvette Delsaut explain this process, showing how fashion designers play a fundamental role in the creation of symbolic production in fashion by having ‘the power to define objects as rare by means of their signature’.3 Defined by Bourdieu and Delsaut as ‘transsubstantion symbolique’,4 the process of creating value in an object is here related to the immaterial capacity of the signature to imbue value in an object such as a garment. Specifically, the French sociologists define the power of the couturier’s signature as magical, arguing that a ‘couturier transforms an everyday object into a piece of art by signing it’.5 Such a mechanism is indeed at play in fashion ephemera, which all gain significance by what Bourdieu and Delsaut see as the magical capacity of the signature to give value to everyday objects. But, while Bourdieu and Delsaut’s idea addresses the authorial impact of the name in the recognition of value in these ephemeral materials, their study fails to explain the scope of the signature and its capacity to trigger specific knowledge about fashion through a particular type of material, visual or written feature. In fact, Bourdieu is not interested in the materiality of the signed object, nor does he recognize its relevance in the affirmation of the magical power of the signature.6 In his ‘But Who Created the Creator?’ (1998), Bourdieu suggests the capacity of the signature to give value to ‘any kind of object’ (‘perfumes, shoes or even, it’s a real example, a bidet’), ‘without any change in its physical or (thinking of perfume) its chemical nature’.7

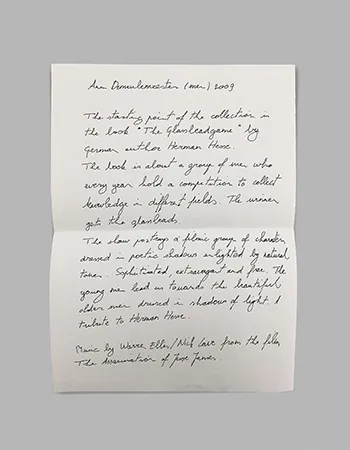

In contrast, fashion ephemera show how signatures – and the matter on which they are inscribed – not only act as symbols of value, but evoke specific meanings, relations and discourses about fashion. Indeed, there is more into a signature or a handwritten text than just a name, as evidenced by Ann Demeulemeester s/s ’09 press releases (Figure 9).8

Figure 9 Ann Demeulemeester s/s ’09 press release. © Collection MoMu Fashion Museum Antwerp.

Contrary to the common, mass-circulated typefaces typically used in press releases by fashion brands, this press release is an handwritten description of the mood of the collection written on A4 white paper, folded in two and resembling a private letter. Demeulemeester’s press release presents the collection and the fashion show through words supposedly handwritten by the designer:

The collection is made of a group of characters dressed in poetic shadows enlightened by natural tones. Sophisticated, extravagant and free. The young men lead us towards the beautiful older men dressed in shadows of light.

(Ann Demeulemeester menswear 2009)

The handwritten text adopts an allusive language that provides no specific information about the collection’s materials, cut and colours, favouring instead a poetic interpretation of garments (‘men dress in shadows of light’). Here Ann Demeulemeester is, to some extent, replaced by her handwritten words that, combined with the poetic content of the press releases, transform the press release from an anonymous text about a collection into a personal interpretation by the designer. There is no concrete mention of the garments nor of the materials used in the collection. Both the handwritten layout of the press release and the rhetoric of the text evoke and pretend to validate the presence of the designer while constructing a discourse on the poetic and personal nature of the collection. As Jacques Derrida argues, handwriting and signatures are two of the most visible indexes of a corporeal gesture as they involve the physical absence of its referent, while recreating its previous presence.9 Following the French philosopher, Sonja Neef, José Van Dijck and Eric Ketelaar explain that handwriting is traditionally regarded as an autography, as an ‘un-exchangeable, unique and authentic “signature” that claims to guarantee the presence of an individual writer’.10 Demeulemeester’s press release works through these meanings and tropes of handwriting, acting as an authentic declaration of the designer, addressed to buyers and journalists who are the recipients of these materials. These actors, in this manner, are not faced with a standard communication from the brand, but what seems like a personal statement presenting a very subjective view on the collection reinforced by the lack of specific details, the tone and the graphical shape of the text alluding to poetry. All these elements concur and seek to control, construct and perform a relationship between the addressee and the designer. But, while these designers’ authorial signs evoke the proximity of the designer, this connection is not necessarily rooted in an original act of signing by the designer and operates similarly to the use of personal inscriptions developed at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth both as both a marketing tool and a strategic instrument in copyright issues.11 According Troy, the signature-label ‘introduced an entirely different, more elusive dimension (to fashion) due to the fact that it signified a creative individual as well as a corporate entity, the identity of the former becoming inextricably linked to the latter’.12 The personification of the designer with the label is to some extent performed by the signature that, similarly to the case of Deumeleemester invitation, reinforces the object with ‘an aura of uniqueness and creative individuality’.13 However, if in the case of labels, the signature becomes a sort of external tool applied to garments to superimpose value to them, in the case of ephemera like Demeulemeester the handwriting becomes the central entity.

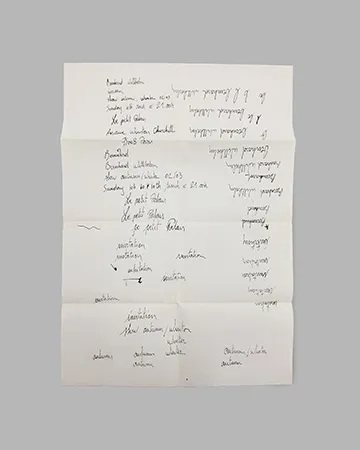

While in garments the signature perpetuates a discourse on authenticity and originality, in the case of ephemera the authenticity seems to eclipse the concept of originality. While the concept of originality is embedded in temporality and involves a hierarchical relation between an original and its copy, the concept of authenticity stands on the affirmation of the real and its closer relation to the author. In these ephemera, the use of the signature or handwriting evokes a discourse about authenticity rather than originality as becomes particularly evident in Bernhard Willhelm a/w ’02–’03 invitation. The invitation is an A3 piece of white paper that, once unfolded, contains multiple handwritten signatures by Bernhard Willhelm as well as handwritten information about the show (Figure 10).

Figure 10 Bernhard Willhelm, s/s ’02–’03 invitation created by the Dutch designer duo Freudenthal and Verhagen. © Collection MoMu Fashion Museum Antwerp.

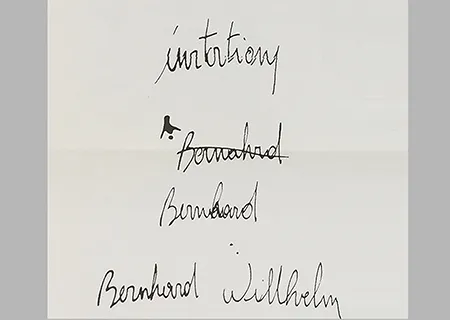

Willhelm’s multiple signatures not only create a direct connection to the designer but also suggest the centrality of the signature to a designer, by performing Willhelm in the act of practising his signature. The multiple signatures, in combination with the reproducible nature of the invitation, show how proximity to the designer is not suggested through a reference to the original act of writing, as it would be in the case of an autograph or a signature on a contract. On the contrary, the Willhelm invitation suggests how signatures or handwriting in ephemera are used as performative to re-enact physical presence, overshadowing an attempt to claim originality but rather mocking the signature’s value in fashion. In the Willhelm invitation, there is not a search for originality but rather authenticity and this is also reinforced by the presence of crossed out names or information in the invitation (Figure 11). Here handwritten information about the show or signatures are struck through or marked over. These ‘printed mistakes’ materialize authenticity by performing the fallible nature of the human act. The mistakes do not create a historical proximity to the event of writing by Willhelm, but they evoke the idea of authentic proximity to the designer through the performance of his fallibility. In this manner, this invitation not only evokes the presence of the designer but also functions as a commentary on the authorial contradictions of the signature in fashion and reproduceable media.

Figure 11 Bernhard Willhelm, s/s ’02–’03 invitation, close-up mistake signature. © Collection MoMu Fashion Museum Antwerp.

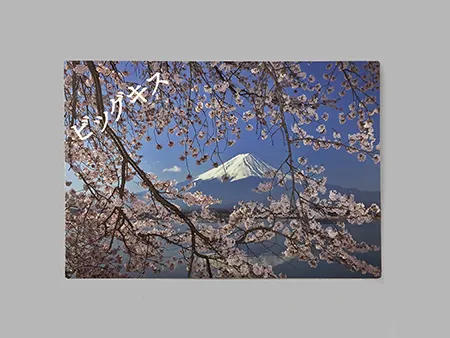

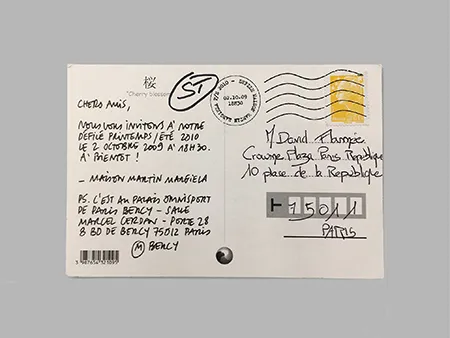

This capacity of the signature becomes particularly relevant in the case of the Maison Martin Margiela s/s 2010 womenswear invitation (Figures 12–13) which takes the shape of a postcard portraying the famous Japanese Mount Fuji with some cherry blossom in the foreground, and some handwritten text on the back.14 In contrast to the previous examples, there is no designer’s signature or individual rhetoric, in accordance with Maison Martin Margiela’s practice of avoiding any individual reference to the founder of the house.

Figure 12 Maison Martin Margiela, s/s 2010 invitation, front. © Collection MoMu Fashion Museum Antwerp.

Figure 13 Maison Martin Margiela, s/s 2010 invitation, back. © Collection MoMu Fashion Museum Antwerp.

Thus, the Margiela invitation shows how the handwriting is not exclusively used for its capacity to recreate the presence of the designer himself in the object, but also works as an allusion to intimate relations built within the fashion industry between brands, designers, buyers or journalists. Here handwriting is not used to recall a direct action of the designer but, rather, intimacy. This immaterial potential of ephemera becomes particular evident in this Margiela invitation due to the material nature of the object on which the handwritten text is printed. By taking the shape of a postcard, the invitation creates a specific type of relationship between its beholder and the designer. As an intimate object usually exchanged between friends, the postcard becomes a material device suggesting closeness between the beholder of the object and the designer.15 While the image of Mount Fuji may refer to the idea of travel as a constant element in fashion imagery, here what is relevant is the type of object and the style of writing used in the invitation. The handwritten text, the intimate language (‘chers amis’), the informal format (including a post scriptum) and the use of the holiday postcard create an intimate relation with the receiver. This invitation produces a discourse of intimacy through an articulated register that does not rely exclusively on handwriting.

This Margiela invitation shows how fashion ephemera may not only be passive indexical signs of a fictive touch by the designer but have a performative value as ‘objects of contact’. Here the signature and the handwriting in fashion ephemera – as much as the material on which they are transcribed – evoke the...