![]()

1 What’s in a Name?: Rebecca’s Story

I, too, worried about the title, and at the time I bought it I offered to give a little extra money if they would change the title of the book. However, … my experience has been that if a book has succeeded with a title … picture producers are foolish to worry about it.

David O. Selznick14

Rebecca is unique among the films of Alfred Hitchcock: the name of the film can be decoupled from that of the director and retain its prominence in film history. In his 1962 interview with François Truffaut and interpreter Helen Scott, the director famously remarked of Rebecca: ‘Well, it’s not a Hitchcock picture.’ There are Rebecca fans who don’t care who directed the film; they read the book first. Rebecca shared a name with and was promoted as a faithful adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 bestselling novel. David O. Selznick savvily launched Hitchcock’s US career by linking the director to the title’s prestige. Rebecca’s reputation as an Oscar-winning classic doesn’t need Hitchcock’s signature.

No one, however – least of all Truffaut, who saw in the film the root of Hitchcock’s predilection for ‘psychological ingredients’15 – would argue that Rebecca does not fit in the director’s oeuvre. Frank S. Nugent, reviewing the film in The New York Times at the time of it release, announces Hitchcock’s arrival as a transatlantic auteur:

Hitch in Hollywood, on the basis of the Selznick ‘Rebecca’ at the Music Hall, is pretty much the Hitch of London’s ‘Lady Vanishes’ and ‘The Thirty-nine Steps’ [sic], except that his famous and widely-publicized ‘touch’ seems to have developed into a firm, enveloping grasp of Daphne du Maurier’s popular novel.16

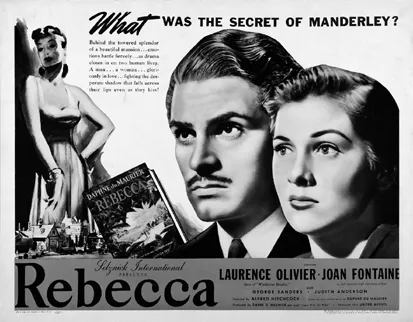

Rebecca’s marketing exploited the popularity of Daphne du Maurier’s novel

Hitchcock’s disavowal is often read in terms of his contentious yet productive relationship with his first US producer. The authoritative story of the film’s production by Leonard J. Leff, Hitchcock and Selznick: The Rich and Strange Collaboration of Alfred Hitchcock and David O. Selznick in Hollywood, tracks the men’s contrasting work styles, tastes and brands. Selznick was chaotic and a meddler, Hitchcock meticulous and controlled. Selznick was invested in character, taking special care with female stars; for Hitchcock, actors were part of an overall visual plan. As Leff characterizes the pair: ‘Both Hitchcock and Selznick were generous though dominating men. Both commanded authority. Both clashed.’17

Rebecca also provides a key case study in Thomas Schatz’s book The Genius of the System, named after André Bazin’s phrase for the greatness achieved by the efficiencies of studio-era Hollywood’s Fordist mode of production. Selznick International Pictures (SIP) was founded in 1936 as an independent studio to skim the cream off that system. With top talent and a production slate limited to prestige pictures, SIP relied on other studios to distribute its films to their theatre chains. Hitchcock was imported as a celebrity in the making to help realize the producer’s vision. Rebecca thus benefits from studio methods and resources as well as an unusual degree of authorial control: a director whose method built the way a finished film would look into the initial treatment; a producer whose near-maniacal attention to detail assured any adaptation capitalized on viewer expectations; a novelist who all but invented the twentieth-century gothic romance.

Scrutiny of how gender informs the politics swirling around the name of the author is only fitting for a film that bears the name of an unseen character and features a nameless protagonist. As a literary figure, du Maurier is more beloved than critically praised. No modernist, she used words to create an immersive atmosphere, her novels and stories are spellbinding masterpieces of mood. While she is undoubtedly a creator of ‘women’s fiction’, she is less given to descriptions of dress and decor than of mental states of doubt and anguish, and in fact the majority of her protagonists are male. Despite a name that demands a cursive font, du Maurier’s own persona was rather butch and reclusive. In effect, she writes with a cinematic quality that she challenges her many adapters to top.

In retelling the story of how the 1940 film version of Rebecca was made, it is not my aim to adjudicate who deserves credit; patently, it is one of film history’s great collaborations. The signatures of all three brand-name creators, as well as distinct traces of less exalted contributors, can be discerned in the finished film. Several of these others are women who found their vocations in the Anglo-American culture industries in the interwar years. The gendered politics of attributing authorship and the connotations of creative brand – the way the production story is told, sold and read into the film text and its waves of reception – are high stakes, and they give Rebecca a prominent place in feminist historiography of classical Hollywood.

A key point of divergence between director and producer of Rebecca was fidelity to the source text; its female author triangulates their rivalry. Hitchcock coaxed a performance from the inexperienced Fontaine that was worthy of I, the book’s distinctive filtering consciousness, and he orchestrated picture, sound and pace to match the gripping atmosphere of the novel. Selznick, acting as du Maurier’s mouthpiece, had the last word – compelling Hitchcock and his screenwriters to scrap an initial treatment and remain faithful to the novel’s scenes and dialogue and later ordering extensive dubbing, including a new version of Fontaine’s famous opening narration. Daphne du Maurier’s influence over the film cannot be reduced to debates over authorial intention, however. After all, du Maurier declined to write the screenplay of Rebecca herself. Rather, the film’s fidelity can be felt in how well it hews to the source text’s radical doubts about fidelity itself, an atmosphere of doubt and duplicity that resonates with female experience. Why does Maxim act as he does? Why does Danvers hate his second wife? Are they in love with Rebecca? Is I?

As Tania Modleski shows in her essay ‘“Never to Be Thirty-Six Years Old”: Rebecca as Female Oedipal Drama’, the kernel of her influential book on Hitchcock and feminist theory, Rebecca is both textually and existentially a particularly telling case of the influence of the feminine in mid-twentieth-century mass culture. As Hitchcock himself explained to Truffaut: ‘It’s a novelette, really. The story is old-fashioned; there was a whole school of feminine literature at the period, and though I’m not against it, the fact is that the story is lacking in humor.’18 Hitchcock’s dismissal of du Maurier’s ‘novelette’ neglects to acknowledge the popular author by name and trivializes the value(s) of her readers. But du Maurier’s influence hovers over the production. Like Rebecca, the third party in the de Winters’s marriage, she is ultimately the source of all the drama.

The du Maurier inheritance

While Daphne du Maurier’s novel might belong to a ‘whole school of feminine literature’, as Hitchcock would have it, the author’s gifts and glamour were distinctly her own.

Du Maurier came from a prominent literary and theatrical family that endears her to the British heritage industry. Her grandfather, novelist and Punch cartoonist George du Maurier, invented the character of Svengali in his 1895 bestselling novel of bohemian France, Trilby. Her parents were famous actor and impresario Gerald du Maurier, with whom she had what the Daily Press calls a ‘complex, adoring, deeply Freudian relationship’,19 and the former actress Muriel Beaumont. The middle-born of three girls, Daphne was Gerald’s favourite: he had wanted a son and she grew up feeling like one. Their closeness may have been cause for her relatively cool relationship with her mother. (Shades of the family romance of Radclyffe Hall’s 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness.) Daphne’s elder sister Angela also became a writer, the younger Jeanne a painter. The three called each other Piffy, Bird and Bing – the Brontë-esque configuration just lacked a rapscallion brother. Perhaps Daphne doubled as their Branwell – she later wrote a biography of him. While her sisters were lesbians whose famous liaisons and longtime companions were public, Daphne struggled with what in family lingo she called her ‘Venetian’ tendencies.20

Daphne du Maurier in the 1930s (Alamy)

The du Maurier family vacationed in Cornwall, which was to be the setting of many of her books and short stories and the place she chose to live and write. Today the town of Fowey has become the centre of ‘du Maurier Country’, a legacy managed by her youngest child, Christian (Kits) Browning. In 1932 she married Major Frederick Browning, known as Boy to his regiment and Tommy to his family, a declared fan of her debut novel, The Loving Spirit. Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Arthur Montague Browning would command British airborne forces during World War II, but behind the façade, the dashing officer was prone to anxiety and breakdowns.

Du Maurier’s role as an officer’s wife was abhorrent to her; she was shy and detested entertaining. Rebecca, with its focus on a tense marriage and an alluring woman known as a successful hostess, was begun in fits and starts in summer 1937 in Alexandria, Egypt, where Browning was stationed. With young daughter Tessa and baby Flavia back in England with their nanny, Daphne planned a book about: ‘roughly, the influence of a first wife on a second … Little by little I want to build up the character of the first in the mind of the second … until wife 2 is haunted day and night.’21 For the imposing ancestral home, the author drew inspiration from Menabilly, a boarded-up Cornwall estate she admired. Once back in England in spring 1938, she finished the novel in record speed.

Over decades in the course of her prolific career, du Maurier was asked so many times about the beloved novel that she must have felt about Rebecca the way Judy Garland did about rainbows. While she had discussed with her publisher Victor Gollancz the objective of writing a bestseller, du Maurier wasn’t at all sure that Rebecca, which she thought ‘psychological and rather macabre’, would be well received.22 Her editor Norman Collins reassured her, immediately recognizing that the manuscript ‘contains everything that the public could want’.23 Published in August 1938 in England and a month later in the US amid great anticipation, the novel was an instant hit. Critics recognized its power even when they treated its popular appeal with condescension. ‘The fearlessness with which Miss du Maurier works in material so strange … is magnificent’, wrote Frank Swinnerton in the Observer, in an emblematic review.24

Du Maurier was annoyed at the novel’s billing as a ‘grand romance’ but happy with the sales; perhaps the dissonant elements, what she thought ‘rather grim’ and ‘unpleasant’ about the novel and its depiction of marriage, were as appealing to readers at the time as its normative ones.25 Amid the publicity onslaught, which included newspaper serializations and considerable interest in the film rights, the writer did her best to avoid public appearances by busying herself with a theatrical adaptation. Produced at London’s Queen Theatre in 1940, Rebecca the play fea...