![]()

1 Beginnings

James Cameron and his co-screenwriter and producer, Gale Anne Hurd, first met in their mid-twenties, when they were both employed by Roger Corman. They were among the last graduates of the New World Pictures company before Corman sold it and moved on. To Cameron and Hurd, as to other aspiring film-makers from Francis Ford Coppola in the 1960s to Joe Dante in the 1980s, Corman offered an opportunity: in return for a willingness to accept strict financial and creative constraints, they would have the chance to work on movies in a variety of capacities. It was the closest Hollywood had to a functioning apprenticeship system for directors and producers.

Hurd worked as a production assistant on two rousing thrillers directed by Lewis Teague and written by John Sayles: The Lady in Red (1979), a noirish tale about the ex-girlfriend of John Dillinger, and Alligator (1980), about a giant alligator terrorising an American town. Then she co-produced with Roger Corman Smokey Bites the Dust (1981), a trashy thick-eared work, for which the car-chase sequences were simply snipped out of earlier Corman films such as Eat My Dust (1976) and Grand Theft Auto (1977; this film was Ron Howard’s directorial debut).

Cameron, in Film Comment, recalled his younger self as ‘interested in photography and design-related special effects’ and he reached his zenith at New World Pictures with five credits on Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), a characteristic Corman project, transposing The Magnificent Seven (1960) into space. He did ‘everything from special effects to production design to a little bit of second unit to post-production work as a matte artist’.

The influence of the Corman industrial process on Cameron and Hurd was decisive. The subject matter was restricted to familiar genres and past films were raw material to be imaginatively plundered. Movies had to be made quickly and cheaply, yet they discovered what could be achieved with the most limited of resources. There were few professional barriers. Everybody got involved with everything, and for Cameron this was crucial:

You see with some filmmakers where they begin to delegate too much authority. They’re not in control of the nuances that give texture to a film like Das Boot, let’s say, where every scene and every shot has some thought behind it. People get the smell of a movie that is too glossy or too packaged. They tend to like underdog movies.

In her famous jeremiad, ‘Why Are Movies So Bad? Or, The Numbers’, first published in The New Yorker in June 1980, Pauline Kael lamented the results of using so many untrained and unprotected first-time directors, technically ignorant, unused to working with actors, ill-at-ease on a movie set. This was never to be Cameron’s problem. By the time he went out on his own, he had a basic technical grasp of every aspect of modern film-making, from operating the camera to the most arcane details of special effects. He could write a script and he could storyboard a scene. When he came to make his own films, he had a knowledge of everybody’s job that gave him a more than nominal authority. He could maintain control from a distance with the knowledge that the material he had storyboarded, even if it was created by different people in different places, would ultimately cohere.

In 1981 Cameron supervised the special effects on John Carpenter’s Escape from New York. This is set in a future in which New York City has become so squalid that it has been abandoned, sealed off and turned into a prison. When the US president’s plane crashes into the city, Kurt Russell is sent in to extricate him. The initial idea was compelling and the grungy setting was effective, but the story remained curiously undeveloped.

In the same year, Cameron directed his first film, Piranha II: Flying Killers (1981), a sequel in name only to the witty 1978 original by the recent Corman graduate Joe Dante. It has far less in common with Cameron’s later work than any of the films he had previously worked on, even before it was heavily recut by the Italian producer, partly to include a sequence of half-naked women sunbathing on a yacht. Cameron himself has only commented that he would have done anything that gave him a chance to direct. It was an uninteresting and insignificant film which did nothing for Cameron except give him the title of director.

Escape from New York (1981); Piranha II: Flying Killers (1981)

![]()

2 Borrowings

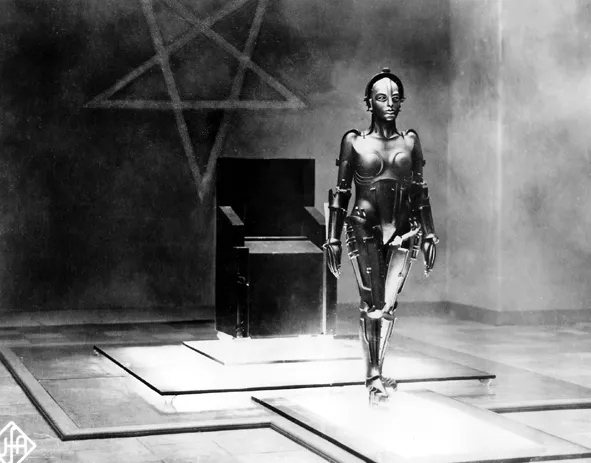

According to James Cameron, The Terminator began as an image in his mind of a robot walking out of a fire. Probably he was remembering the scene in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), in which the robot imitation of Maria is burned at the stake and the metal machine beneath is revealed. It is not sufficient merely to say that The Terminator teems with echoes of this kind. It is built out of them.

Cameron has been open about the cinematic memories that feed into his work. Soon after the release of The Terminator, he told an interviewer from Cinefantastique (October 1985):

Metropolis (1927)

If I really think about the influences that helped shape the story, the entire feeling can be traced back to some ’50s science fiction films and Outer Limits episodes. The thing that The Outer Limits had, that always impressed me visually, was its use of the deep focus film noir look of the ’40s films and the German Expressionist movies of the ’30s.

Parallels were speedily alleged with a specific 1964 episode of The Outer Limits called ‘Soldier’, written by Harlan Ellison, which Cameron was known to have seen. Further comparisons were made, during this interview, with a machine-against-man story also written by Ellison, ‘I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream’, which begins in words similar to the text at the beginning of The Terminator:

The Cold War started and became World War Three and just kept going. It became a big war, a very complex war, so they needed computers to handle it. They sank the first shafts and began building AM (Allied Mastercomputer) … and everything was fine until they had honeycombed the entire planet, adding this element and that element. … In rage, in frenzy, the machine had killed the human race. … With the innate loathing that all machines had always held for the weak, soft creatures who had built them, he had sought revenge.

Other resemblances were also asserted. Another 1964 Outer Limits episode, ‘Demon with a Glass Hand’, featured a time-travelling robot entrusted with the fate of the human race. In a famous Star Trek episode, ‘City on the Edge of Forever’, McCoy travels back to twentieth-century Earth and his arrival is reminiscent of Reese’s in The Terminator, in a similar back alley witnessed by a down-and-out in a doorway. But isn’t this an example of a resemblance caused by practical responses to the same problem? The time traveller has to arrive in a city, but if he appears in a busy street, there will be distracting complications that have nothing to do with the story. The same could be said of other resemblances. Cameron certainly knew Ellison’s work, but his vision of a future conflict between man and the technology he has created goes back to Prometheus. More recently, the battle between machines and people had been dramatised in Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove (1963) and 2001, in John Carpenter’s Dark Star (1974) and in numerous episodes of Star Trek. The issue was concluded as murkily as it had begun. After tortuous, acrimonious legal proceedings, a settlement was reached with Ellison, the enactment of which has itself been a matter of constant dispute.

In the aftermath of a sudden success, accusations of this kind are routine. Not all of them are unjustified. Dorothy Parker famously said that the only ‘ism’ Hollywood understood was plagiarism. Studio lawyers prefer to use terms like hommage (using the word in French makes it seem more artistic), coincidence or even ‘fragmented literal similarity’. In fact, the more examples are produced against The Terminator, the less damaging they seem. They merely demonstrate the degree to which these ideas formed a bottomless pool of material, available to anybody who could find a use for them.

In an ingenious essay identifying the archetypes used in Casablanca (1942), Umberto Eco pointed out in his book Faith in Fakes that what Casablanca had done unconsciously, more recent films have done ‘with extreme intertextual awareness’. He continued:

It would be semiotically uninteresting to look for quotations of archetypes in Raiders or in Indiana Jones: they were conceived within a metasemiotic culture, and what the semiotician can find in them is exactly what the directors put there. Spielberg and Lucas are semiotically nourished authors working for a culture of instinctive semioticians.

Like Spielberg and Lucas, Cameron belongs to a generation of cinematically literate directors who are highly conscious of what they are doing. Cameron can draw on anything, from Un chien andalou, when Schwarzenegger slices through his damaged eye, to the slasher movies that were so commercially successful in the early 1980s. Accusations of plagiarism are beside the point. Like many artists in all fields, Cameron has considerable skill in finding things that have worked for other people or, more interestingly, that haven’t worked for other people but can work for him.

Westworld (1973)

A typical example is his obvious debt to Michael Crichton’s debut film, Westworld (1973). This is about a Western theme park where adults can go and play at cowboys, shooting a robot who looks like Yul Brynner and bedding the local whores. When – as in Crichton’s later Jurassic Park (1992) – the exhibits turn on the guests, the hero is pursued by the vengeful Brynner android. Cameron drew on two separate aspects of the film. Crichton’s most striking visual coup was to show us the world through the android’s electronic eyes, an electronic mosaic, a surprisingly touching effect which enabled the audience to identify briefly with the creature. Cameron borrowed the idea and enriched it in The Terminator, and made even subtler use of it in the sequel. If the lesson of The Terminator and Westworld was that to share a character’s point of view is necessarily to identify with it and even feel something for it, then one of the logical methods of preventing any audience involvement with the even more advanced cyborg that pursues Schwarzenegger is to deny us any participation in his point of view. By contrast, Cameron makes more detailed use of the old terminator’s point of view and the film’s most poignant moment is a technological effect: after the terminator has sunk himself into the vat of molten metal at the climax of Terminator 2, we see his visual display crackle, collapse and fade to a dot.

Cameron’s second use of the film arose from his recognition of how an initially potent idea had remained oddly unsatisfying. In Westworld, Crichton showed little interest in the details of how the androids might plausibly work. It was this abnegation that stimulated Cameron’s imagination, as he told Film Comment:

I was thinking of an indestructible machine, an endoskeleton design, which had never been filmed as such. We’d had things like Westworld, where Yul Brynner’s face falls off and there’s a transistor radio underneath – which is not visually satisfying, because you don’t feel that this mechanism could have been inside moving those facial features. So it started from the idea of doing this sort of definitive movie robot, what I’ve always wanted to see.

Cameron has a reputation as a director who is preoccupied with technology but this mechanical skill is accompanied by a film fan’s sense of what the audience wants to be shown. He devoted scarcely any of his limited resources to the time machine at the beginning of The Terminator, because he rightly calculated that the audience would accept that as a given. But since we are told so much about the cyborg’s capabilities, and then get to see it in action, we want to be shown the details of how it works.

The obvious influence of the psychopathic murderer in John Carpenter’s highly successful Halloween (1978) is another example of Cameron’s creative borrowing. Carpenter had based the entire structure of his film on the progress of an unstoppable killer, defying all traditions about character and suspense as to how he could be caught. The killer had no psychological motivation and was also, in some unexplained way, non-human, and apparently impossible to kill. As an abstract experiment in cinematic suspense it was interesting, as a cinematic narrati...