![]()

1 The Production: A Monster and a Grave

From day one, Takahata kept his distance from the studio he helped launch. At Ghibli’s registration ceremony in June 1984,12 he refused to sign the official paperwork, telling Miyazaki – who was ready to sign – that an artist had no business putting his name on such documents. And so, contrary to received wisdom, Takahata technically didn’t co-found the studio. Rather than hold a formal title within Ghibli, he said he wanted to be seen as something like a ‘playwright in residence’.

Takahata’s little rebellion proved prophetic. Both he and Miyazaki made all their subsequent features at Ghibli, but the studio grew more closely associated in the public imagination with Miyazaki, a prolific film-maker and charismatic media presence. Through a string of monumental blockbusters, his personal style came to be identified with the Ghibli brand. Meanwhile, Takahata gently subverted that brand with a handful of narratively and visually experimental features, culminating in the radical abstractions of his swansong, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (Kaguya-hime no monogatari, 2013). With this work, he literally distanced himself from Ghibli, relocating production to a satellite studio while Miyazaki occupied the main building. As often as not, Takahata’s features disappointed at the box office, and in later years he expressed gratitude to Miyazaki for effectively subsidising his film-making.

In a sense, Miyazaki was only repaying a debt. His own career owed much to Takahata, five years his senior, who spotted his talent early on and became his mentor of sorts. The pair met in the 1960s at Toei Animation, a pioneering studio that aspired to establish itself as the ‘Disney of the East’ with its lavishly produced features. Takahata had started at the company as an assistant director, Miyazaki as a lowly in-betweener.13 Having built a rapport through union activities, they collaborated on Takahata’s debut feature as director, The Little Norse Prince, an epic tale of mythological derring-do. Miyazaki served chiefly as an animator and layout artist,14 displaying his formidable abilities as a draughtsman – a great asset to Takahata, whose own talents did not really extend to drawing.

Their collaboration endured throughout the 1970s, when they left Toei to make TV series and specials for various studios. Takahata directed and Miyazaki played key roles in visual development and production. With Heidi, Girl of the Alps (Arupusu no shōjo Haiji, 1974), they embarked on a run of serials based on classic Western novels, which eschewed the high fantasy of their Toei work in favour of rich explorations of social and psychological themes: poverty, xenophobia, urbanisation, the anxieties of early adulthood. These were novel themes for TV anime, and the series raised the medium’s production values about as high as they could go; Takahata and Miyazaki chafed at the constant deadlines and financial constraints.

Their creative partnership frayed as Miyazaki’s own directorial career took off in the late 1970s. Meanwhile, Takahata directed two acclaimed features, Chie the Brat (Jarinko Chie, 1981) and Gauche the Cellist (Sero hiki no Gōshu, 1982), without his old comrade. But they were reunited when Miyazaki called on Takahata to produce his features Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (Kaze no tani no Naushika, 1984) and Castle in the Sky (Tenkū no shiro Rapyuta, 1986). The former’s relative commercial success led to the founding of Ghibli, and the latter became its first release. The studio was established as a division of Tokuma Shoten, a publisher that had branched out into film production by investing in Nausicaä.

From the outset, Ghibli defined itself by spurning TV series, franchise films and straight-to-video productions – the staple of most Japanese animation studios – and concentrating on original theatrical features. Following the example of Toei Animation, it committed to producing works with greater detail and fluidity than the cost-cutting ‘limited animation’ that defined the look of so much anime.15 In brief, Ghibli was set up to accommodate the vast creative ambitions of its two core directors, Miyazaki and Takahata. As its co-founder Toshio Suzuki said, ‘[Their] wishes were paramount in whatever was done.’16 The riskiness of this high-minded policy was swiftly exposed by the studio’s second project.

This anarchic feeling

Suzuki started the 1980s as an editor at Animage, Tokuma Shoten’s influential animation periodical. In this capacity, he championed the two directors’ films and enjoyed privileged access to their workplaces, where his strategic instincts established him as an effective behind-the-scenes fixer. This role was gradually formalised throughout the decade, until he officially joined Ghibli as a full-time producer in 1989.

A film about the Pacific War was first mooted in early 1986, while Takahata was visiting the Animage offices. Suzuki’s boss remarked that children alone had remained lively after defeat, and proposed a feature on this subject. Takahata was taken by the idea, but the search for suitable source material led him and Suzuki to a story with a very different message: Grave of the Fireflies. Nosaka’s searing novella had made a splash on its release in 1967, impressing the literary establishment – it won the prestigious Naoki Prize17 – as well as the teenage Suzuki, who fantasised about entering the film business and adapting it. By 1986, though, the novella was almost out of print. Suzuki proposed an adaptation to Takahata, who agreed.

Meanwhile, Castle in the Sky was released in August to moderate success, enabling Ghibli to start work on a follow-up. This was when Miyazaki decided to revive a long-gestating pet project. For around a decade, he’d been mulling a story of a girl communing with forest spirits in the Japanese countryside. He wanted Takahata to direct the film, but Takahata refused: he had no interest in helming a feature written and designed by his colleague.18 Taking the reins himself, Miyazaki presented the idea to Tokuma Shoten’s executives, who had hoped for another action-packed epic in the vein of his previous features. Unable to foresee the vast revenues that My Neighbour Totoro (Tonari no Totoro, 1988) would eventually generate through licensing deals, they dismissed Miyazaki’s ‘monster’ (obake) film.

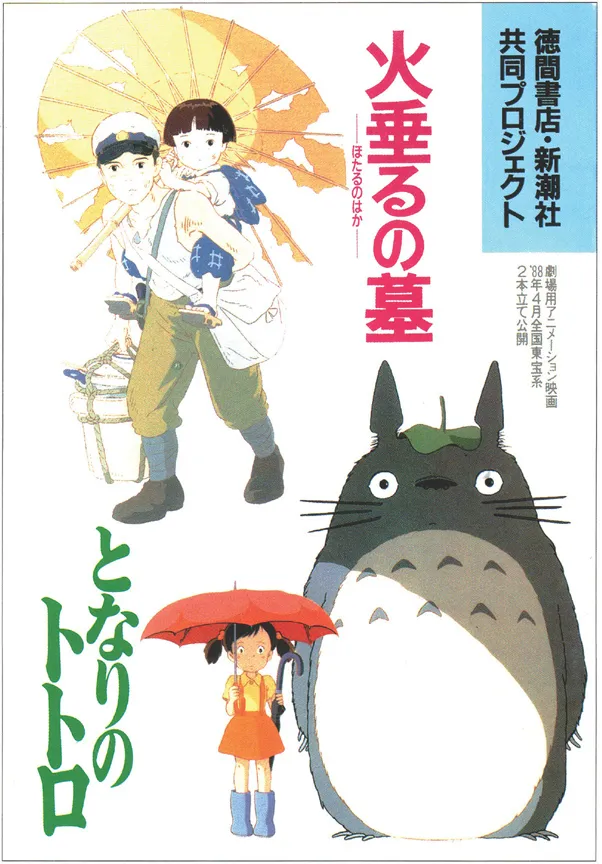

Suzuki believed in Totoro. Searching for a way to save the project, he decided to pitch it alongside Takahata’s Fireflies in a double bill. According to some scholars,19 Suzuki’s rationale was that the educational value of a film about the war would draw schoolchildren, guaranteeing both films an audience – in an inversion of the dynamic that was later to develop, Takahata’s film would underwrite Miyazaki’s. However, Suzuki himself has refuted this. Rather, he anticipated that the two directors would be spurred on to do good work by a sense of rivalry. Yet the double bill still failed to convince the executives, whose response was categorical: ‘You idiot! First a monster and now a grave, too?!’20

As it happened, Shinchosha, the venerable publisher of Nosaka’s novella, was planning to break into film production, as Tokuma Shoten had done before it. Hearing this, Suzuki changed tack and convinced Shinchosha that Takahata’s adaptation of their book would be the ideal gateway into the business. If they produced Fireflies, Tokuma Shoten might be persuaded to take on Totoro. The plan hinged on a sly trick of corporate politics: if Shinchosha, as the older company, solicited Tokuma Shoten’s collaboration, the latter would feel obliged to accept. So it proved, and the two publishers struck a deal to co-produce the double bill – an unprecedented arrangement in the industry.

This pact didn’t reassure everyone. Tōru Hara, the experienced producer then serving as Ghibli’s manager, found the plan preposterous. He argued that the young studio was ill-equipped to make two films at once; not even Toei Animation, the vast production house where he had once worked alongside Takahata and Miyazaki, had ever attempted such a thing. In a further blow, the distributor of Miyazaki’s recent features turned the double bill down, explaining that the films didn’t fit its brand. Only after impassioned lobbying by Tokuma Shoten’s president did another company agree to distribute them.

A promotional pamphlet for the double bill. Reprinted with permission from Masahiro Haraguchi, Archives of Studio Ghibli Vol. 2 (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 1996), p. 18

Concept art

Nosaka himself was initially sceptical, too. He had cause to be: over the years, three attempts to adapt his book in live action had failed for various reasons. Most recently, an extravagant producer had suggested recreating the city of Kobe in the Arizona desert and subjecting it to genuine firebombing; the project collapsed when the producer died. By the time Takahata approached him, Nosaka had concluded that no film could ever convincingly depict the hardships and devastated landscapes of his story – the logistical hurdles were too high. Animation hadn’t even occurred to him: ‘I thought animated features were pleasure viewing for summer vacation. A boy’s adventure, or courage, that sort of thing.’21 Upon seeing Ghibli’s concept art, however, he was stunned by the detail with which his narrative world had been rendered. ‘I realized this could only have been done with animation,’ he told Takahata.22

The core production crew started work in Ghibli’s main premises in January 1987. The double bill’s running time was set at 60 minutes per film and its release was scheduled for 16 April 1988. The combined budget came to approximately one billion yen including advertising – a substantial sum for Japanese animation at the time, though dwarfed by Ghibli’s subsequent budgets. As Suzuki later recalled, ‘I had this anarchic feeling that it didn’t matter if these two films were Ghibli’s last.’23

A sense of reality

The pairing of Fireflies with Totoro, an irrepressibly sunny film, may seem inappropriate at first glance. What does the scorched earth of wartime Kobe have to do with Miyazaki’s bucolic wonderland? How can an ode to the freedoms of childhood be billed alongside an elegy for the young victims of war? And in what order should they be shown?24

In fact, the films are bound by numerous narrative and thematic parallels; a full comparative analysis l...