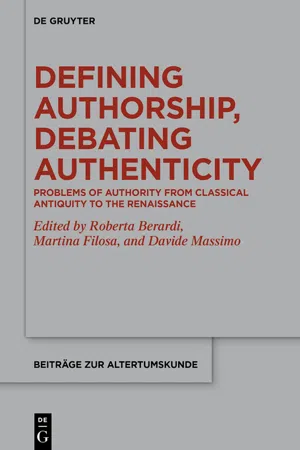

Defining Authorship, Debating Authenticity

Problems of Authority from Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance

- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Defining Authorship, Debating Authenticity

Problems of Authority from Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance

About this book

This volume explores the themes of authorship and authenticity – and connected issues – from the Classical Antiquity to the Renaissance. Its reflection is constructed within a threefold framework. A first section includes topics dealing with dubious or uncertain attribution of ancient works, homonymous writers, and problems regarding the reliability of compilation literature. The middle section goes through several issues concerning authorship: the balance between the author's contribution to their own work and the role of collaborators, pupils, circles, reviewers, scribes, and even older sources, but also the influence of different compositional stages on the concept of 'author', and the challenges presented by anonymous texts. Finally, a third crucial section on authenticity and forgeries concludes the book: it contains contributions dealing with spurious works – or sections of works –, mechanisms of interpolation, misattribution, and deliberate forgery. The aim of the book is therefore to exemplify the many nuances of the complex problems of authenticity and authorship of ancient texts.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part 1: Attribution

Semonides or Simonides? A Century–Long Controversy over the Authorship of a Greek Elegiac Fragment

1 Introduction

ἕν δὲ τὸ κάλλιστον Χῖος ἔειπεν ἀνήρ·“οἵη περ φύλλων γενεή, τοίη δὲ καὶ ἀνδρῶν”·παῦροί μιν θνητῶν οὔασι δεξάμενοιστέρνοις ἐγκατέθεντο· πάρεστι γὰρ ἐλπὶς ἑκάστῳἀνδρῶν, ἥ τε νέων στήθεσιν ἐμφύεται. 5θνητῶν δ’ ὄφρά τις ἄνθος ἔχῃ πολυήρατον ἥβης,κοῦφον ἔχων θυμὸν πόλλ᾽ ἀτέλεστα νοεῖ·οὔτε γὰρ ἐλπίδ᾽ ἔχει γηρασέμεν οὔτε θανεῖσθαι,οὐδ᾽, ὑγιὴς ὅταν ᾖ, φροντίδ᾽ ἔχει καμάτου.νήπιοι, οἷς ταύτῃ κεῖται νόος, οὐδὲ ἴσασιν 10ὡς χρόνος ἔσθ᾽ ἥβης καὶ βιότου ὀλίγοςθνητοῖς. Ἀλλὰ σὺ ταῦτα μαθὼν βιότου ποτὶ τέρμαψυχῇ τῶν ἀγαθῶν τλῆθι χαριζόμενος.The man from Chios said one thing best: “As is the generation of leaves, so is the generation of men”. Few men hearing this take it to heart, for in each man there is a hope which grows in his heart when he is young. As long as a mortal has the lovely bloom of youth, with a light spirit he plans many deeds that will go unfulfilled. For he does not expect to grow old or die; nor when healthy does he think about illness. Fools are they whose thoughts are thus! Nor do they know that the time of youth and life is short for mortals. But you, learning this at the end of your life, endure, delighting in good things in your soul.1

2 A Century–Long Authorship Controversy

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Attribution

- Part 2: Authorship

- Part 3: Authenticity

- List of contributors

- Index