![]()

Small Is Profitable

Nearly everywhere we look, the stirrings of a revolution are becoming increasingly clear: people are farming differently; and we see signs of landowner resistance with a focus on local production, concern for the environment, and citizenship.

— Hélène Raymond and Jacques Mathé

Une agriculture qui goûte autrement. Histoires de productions locales, de l’Amérique du Nord à l’Europe, 2011

EVERYWHERE AROUND THE WORLD, people’s eyes are being opened to the ravages of industrial agriculture: pesticides, GMOs, cancer, agribusiness. Along with this growing awareness is an increasing consumer demand for healthy, local, organic food. Alternative modes of selling and purchasing food are also gaining ground, visible not only in the mushrooming farmers’ markets but also through community-supported agriculture, or community-shared agriculture (CSA) schemes. This system is a direct exchange between producers and consumers. The consumer buys a share in the farm’s production at the beginning of the season, thus becoming a partner in the endeavor. In exchange, the farm commits to providing quality produce, usually harvested the day before, or even the same day. In addition to issues of quality, this model of food distribution addresses people’s desire to have a relationship with the farmers who grow their food.

These ideas are making headway in Quebec: Équiterre, which oversees one of the largest networks of organic farmers and citizens in support of ecological farming, has brilliantly complemented the notion of the family doctor with that of the “family farmer.” Alternative modes of food distribution now represent a growing niche, and moving out to the country to make a living in agriculture is now a viable option for young (and not-so-young) aspiring farmers.

My wife and I began our farming career in a very small market garden, selling our veggies through a farmers’ market and a CSA project. We rented a small piece of land (⅕ of an acre) where we set up a summer camp. It didn’t take much investment in the way of tools and equipment to get us up and running, and our expenses were low enough that we were able to cover our farming costs, earn enough money to make it through the winter, and even do some travelling. Back then we were content just to be gardening and to be making ends meet.

Eventually, however, there came a time when we felt the need to become more settled; we wanted to build a house of our own and put down roots in a community. Our new beginning meant that our market garden would have to generate enough income to make payments on the land, pay for the construction of our house, and keep the family afloat.

To accomplish this, we could have followed a route similar to that taken by all the other growers we knew: invest in a tractor and move towards a more mechanized growing system. Instead, we opted to stay small-scale and continue relying on hand and light power tools. From the outset, we had always believed that it was possible—and even preferable—to intensify production through gardening techniques. To grow better instead of bigger became the basis of our model. With simplicity in mind, we began researching horticultural techniques and tools that could make farming on our one-and-a-half-acre plot a viable reality.

After much research and many discoveries, our journey led us to what is now a productive and profitable micro-farm. Every week, our market garden now produces enough vegetables to feed over 200 families and generates enough income to comfortably support our household. Our low-tech strategy kept our start-up costs to a minimum and our overhead expenses low. The farm became profitable after only a few years of production, and we have never felt the pinch of financial pressure. Just like in the beginning, gardening is still our main focus, and even though there have been a lot of changes around the farm over the years, our lifestyle has remained the same. We don’t work for the farm; the farm works for us.

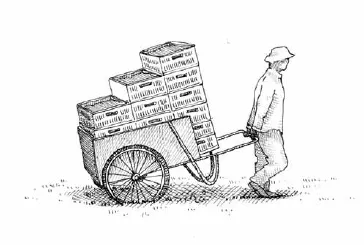

We decided to brand ourselves specifically as market gardeners (jardiniers-maraîchers in French) to emphasize the fact that we work with hand tools. Unlike most contemporary vegetable producers, who grow in vast fields, we work in gardens where our fossil fuel input is relatively low. The features that characterize our operation—high productivity on a small plot of land, intensive methods of production, season extension techniques, and selling directly to public markets—are all modelled after the French tradition of maraîchage, although our practices have also been influenced by our American neighbors. The greatest influence on our work has been the American vegetable grower Eliot Coleman, whom we have visited and met on several occasions. His book The New Organic Grower guided us and helped us see that it truly is possible to turn a profit on less than two cultivated acres. Coleman’s shared experience and his innovation in techniques for growing vegetables on small plots were a gift to us, and we owe him a great deal.

Of course, most established farmers would probably tell us that farming without a tractor is too much work and that we are too young to appreciate how much easier our lives would be with mechanization. I disagree. The cultivation techniques described in this book actually reduce the amount of work required for field preparation, and planting crops more closely together greatly reduces weed pressure. And though most of our gear and tools are hand-powered, they are quite sophisticated and designed to make tasks more efficient and ergonomic. All in all, apart from harvesting, which accounts for the bulk of our work, our productivity and efficiency are extremely high. The manual labour we do is pleasant, lucrative, and very much in keeping with a healthy lifestyle. More often than not, we enjoy the sound of birdsong as we work, rather than the din of engines.

None of this is to say that I object to all forms of mechanization. Of the most successful farms I have visited, the majority were highly mechanized—Eliot Coleman’s being the exception. I would simply put it this way: using a tractor and other machinery for weeding and tilling does not by itself guarantee that farming will be more profitable. When choosing between a non-mechanized approach and machinery such as a two-wheeled tractor, aspiring farmers must always weigh the pros and cons, especially if they are just starting out.

Can You Really Live off 1.5 Acres?

When it comes to commercial vegetable growing, the idea of a profitable micro-farm is sometimes met with scepticism by people in the farming world. It is even possible that some naysayers would try to discourage an aspiring farmer from starting an operation like ours, stating that production simply won’t be enough to make ends meet for a family. I encourage aspiring farmers to take this kind of scepticism with a grain of salt. Attitudes are beginning to shift as micro-farming in the United States, Japan, and other countries is demonstrating the impressive potential of biologically intensive cropping systems geared towards direct selling. Our farm in Quebec, Les Jardins de la Grelinette, is living proof of this. In our first year of production on rented land, our farm brought in $20,000 in sales with less than one quarter of an acre under cultivation. The following year, our sales more than doubled on the same garden size, rising to $55,000. In our third growing season, we invested in new tools and land, settling on our own farm site in Saint-Armand. By increasing our area under cultivation to one and a half acres, we were able to increase our gross sales to $80,000. When our sales broke the $100,000 mark the following year, our micro-farm reached a level of production and financial success that most people in the agriculture industry believed to be impossible. When our sales figures were made public through a farming competition, our business won a prize for its outstanding economic performance.

For the last ten years, my wife and I have had no other income than the one we obtain from our 1½-acre micro-farm. Many other small-scale growers make better than a living wage on small intensively cultivated plots, and there should not be any doubt that it is possible to have a career in market gardening. In fact, one can imagine making a pretty decent livelihood. A well-established, smoothly running market garden with good sales outlets can bring in $60,000 to $100,000 per acre annually in diverse vegetable crops. That’s with a profit margin of over 40%—a figure that stacks up favorably against margins in many other agricultural sectors.

Our daily life in the garden is in tune with the passing seasons and in line with how we want to live. Market gardening is hard work, but also rewarding and fun.

Not Just Making a Good Living, but Making a Good Life

The popular myth of family farms persists: we are tied down to the land, we work seven days a week, we never have time off, and we just barely scrape by financially. This image probably has its roots in the real-life struggles experienced by most conventional farmers, who are caught in the strangle-hold of modern agriculture. It is true that being a mixed vegetable grower is hard work. Rain or shine, we are up against the vagaries of a highly unpredictable climate. Bumper crops and seasons of plenty are far from guaranteed, and a hefty dose of pluck and commitment is required to make it through—particularly during those first few years, when one is still building infrastructure and a customer base.

Our vocation is nevertheless an exceptional one, defined not by the hours spent at work or the money earned, but by the quality of life it affords. Believe it or not, there is still plenty of free time left over when the work is done. Our season gradually gets started in the month of March and finishes in December. That’s nine months of work; three months off. The winter is a treasured time for resting, travelling, and other activities. To anyone who pictures farm life as endless drudgery, I would assert that I feel quite fortunate to live in the countryside and work outdoors. Our work offers us the opportunity to become partners with nature on a daily basis, a reality that not many other professional careers can offer. Unlike employees of big companies living with the constant threat of layoffs, I have job security. That’s saying a lot.

After having spent so much time at the computer writing this book, I would also add that the physical demands of market gardening are actually easier on one’s health than sitting in front of a computer screen all day. By saying so, I hope to reassure some readers that gardening as a living is not so much a question of age as one of will. Whether or not you have a background in farming, you can learn everything you need to know in this time-honored vocation if you are serious and motivated. You need only invest your time and enthusiasm.

Since our farm began hosting interns just getting their feet wet in the world of agriculture, I have noticed that most aspiring farmers I meet are drawn to the fields for one fundamental reason. It’s not just that they want to be their own boss and get out in the fresh air as much as possible—most of them are looking for work that brings meaning to their lives. I can understand this, because I have found much fulfillment in being a family farmer. Our toil in the garden is rewarded by all the families who eat our vegetables and thank us personally every week. For anyone looking for a different way of living, market gardening offers a chance not only to make a good living, but also to make a good life.

![]()

Succeeding as a Small-Scale Organic Vegetable Grower

To obtain the best yield from the soil, without excessive expenses, through the judicious selection of crops, and through appropriate work: such is the goal of the market gardener.

− J. G. Moreau and J. J. Daverne, Manuel pratique de la culture maraîchère de Paris, 1845

BECAUSE OUR MICRO-FARM has garnered so much media attention in recent years, farmers of all stripes and many agronomists have been coming to meet us and visit our gardens. These people, most of them only familiar with modern large-scale conventional farming, are curious about our work because we challenge the belief that the small family farm cannot stay afloat in today’s economy. Despite our decade of experience in proving the viability of a micro-farm, most of these visitors remain unconvinced. They find it difficult to wrap their heads around the fact that we have no plans to make major investments and that we intend to stay small and continue working with hand tools. A bank loan officer who visited us adamantly declared as she left that we were not real business people, and that our farm was not a real farm!

Our farming choices may be easier to understand when one stops to consider the obstacles that beginning farmers must face when they are just getting started. For us, the decision to grow vegetables on a small plot of land, while minimizing start-up investments, simply had to do with our fi...