- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Blackface

About this book

A New Statesman essential non-fiction book of 2021

Featured in Book Riot's 12 best nonfiction books about Black identity and history

A Times Higher Education Book of the Week

2022 Finalist for the Prose Awards (Media and Cultural Studies category)

Why are there so many examples of public figures, entertainers, and normal, everyday people in blackface? And why aren't there as many examples of people of color in whiteface? This book explains what blackface is, why it occurred, and what its legacies are in the 21st century. There is a filthy and vile thread-sometimes it's tied into a noose-that connects the first performances of Blackness on English stages, the birth of blackface minstrelsy, contemporary performances of Blackness, and anti-Black racism. Blackface examines that history and provides hope for a future with new performance paradigms.

Object Lessons is published in partnership with an essay series in The Atlantic.

Featured in Book Riot's 12 best nonfiction books about Black identity and history

A Times Higher Education Book of the Week

2022 Finalist for the Prose Awards (Media and Cultural Studies category)

Why are there so many examples of public figures, entertainers, and normal, everyday people in blackface? And why aren't there as many examples of people of color in whiteface? This book explains what blackface is, why it occurred, and what its legacies are in the 21st century. There is a filthy and vile thread-sometimes it's tied into a noose-that connects the first performances of Blackness on English stages, the birth of blackface minstrelsy, contemporary performances of Blackness, and anti-Black racism. Blackface examines that history and provides hope for a future with new performance paradigms.

Object Lessons is published in partnership with an essay series in The Atlantic.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Why Write This Book?

When my son, Dash, was in the third grade from 2011 to 2012, he attended a private school that prided itself on its academic rigor. In fact, each eight-year-old student was required to do a year-long research project on an influential person in history. As the culmination of their research, the kids had to make a poster that highlighted their person’s life and accomplishments, and then dress up as their person and answer questions as if they were the famous person during the poster presentation. It was a lot of work, and the presentations were impressive. That year there were astronauts and entertainers, politicians and athletes, humanitarians and playwrights.

And there were also several little white children in full-on blackface makeup—they were “Martin Luther King Jr.,” “Serena Williams,” and “Arthur Ashe.” As I walked around the room, looking at the posters and interacting with the famous, historical people, I was stunned when I saw the first blacked-up child. Attempting to keep my face neutral, I asked questions about “Martin Luther King Jr.’s” life and praised the student for her hard work. It was clear that she had immense respect and reverence for Dr. King—he was her hero. She beamed through her blacked-up face, proud to be him. I stared on in an attempt not to register my horror and dismay.

After taking this in, I immediately went to find the school’s principal to ask what was happening. Was makeup allowed? Encouraged? Did the teachers facilitate this? Were the parents involved? What conversations had they had about cross-racial impersonation, even if this all occurred under the auspices of hero worship? The principal seemed not to understand what I was saying—that the children’s performances were veering dangerously close to blackface. He seemed confused and indicated that he thought I was making a tempest in a teapot. I could see in his eyes that he was reading me as an irrationally angry black woman, and then he asked, “What is blackface minstrelsy anyway?”

I was gobsmacked by the question. In fact, I was quickly becoming the angry black woman he thought I was, wondering why I should have to explain American history to an American educator at a tony private school. Why didn’t he know this already? Why was it my job to teach him our shared history? Why did I have to pay this black tax on top of the tuition I was already paying? I was enraged by his ignorance because it made starkly visible the inequality of our experiences. I had to know this history because it affects me and my children in the twenty-first century; he did not because of his white privilege, which was expressed through an implicit notion that this history did not, does not, and will not impact him or the white charges in his private school.

When my anger was less blinding and began to subside (I was a rationally angry black woman, after all!), I recognized that the principal’s ignorance was symptomatic of the American amnesia with regard to racism and racial violence. The history is difficult, and the solutions are neither readily apparent nor easily achievable; so forgetting, while not necessarily natural, is widespread, pervasive, and common. And forgetting blackface minstrelsy—a performance tradition from the early nineteenth century—is easy to accomplish because it happened back then (i.e., it’s over and has no resonance in today’s world).

The principal’s reaction, while unfair, was actually normal. But I am not content with this normal state of being. I need to be able to make it as impossible for him to forget as it is for me—it is both of our history after all. I need to be able to combat the extensive drift toward amnesia. This book is my attempt. This book is a defiant and material act of remembering our collective American history. This book is for every parent, teacher, friend, or colleague who has had to face and address similar questions about the uses, problems, or issues with blackface.

In order to explain what blackface is, why it occurred, and what its legacies are in the twenty-first century, I will ask repeatedly why the handful of black and brown children in my son’s third-grade class did not whiten up to be “William Shakespeare,” “Sir Isaac Newton,” and their other white heroes. Not one of the children of color in my son’s class applied racial prosthetics to look white. Why not? Were they less committed to the fidelity of their representations? Did they know something the white children did not? Or, did the white children know something the black and brown children did not? These questions haunt this book and fuel my writing of it.

2 Megyn Kelly, Justin Trudeau, or (Fill in Another Public Figure’s Name)

In order to explain what blackface is, I begin with several examples from recent history. In fact, the four examples detailed below all occurred within the scope of one year—from October 2018 to September 2019. I quote extensively from the individuals involved because part of what propels the use of blackface is white people’s belief in their white innocence. When defending, explaining, and even apologizing for the employment of blackface, white people rely on the logic and rhetoric of their innocence. In fact, they frame blackface as either an act of celebration and love, or as an act of imitation and verisimilitude. The logic of white innocence unites the actions of the disparate public figures who have engaged in blackface as adults, and it also unites their defenses of their actions. Despite their various political stances, their actions are yoked together by the inherent white supremacist logic of white innocence.

Example #1: On the October 23, 2018, show Megyn Kelly Today (NBC, episode 212), Megyn Kelly, Melissa Rivers, Jenna Bush Hager, and Jacob Soboroff discussed controversial Halloween costumes on a segment entitled “Halloween Costume Crackdown.” Kelly began the segment by declaring that political correctness had gone too far. She reported that Kent University in the UK had issued a warning to its students not to wear controversial Halloween costumes. When her interlocutors indicated that they thought this was reasonable to ensure that the students did not offend others (a Nazi costume was roundly denounced as offensive and inexcusable), Kelly was both perplexed and annoyed. She responded:

But what is racist? You get in trouble if you are a white person who puts on blackface for Halloween, or if you are a black person who puts on whiteface for Halloween. Back when I was a kid that was okay as long as you were dressing up as, like, a character. . . . There was a controversy on the Real Housewives of New York with Luann [de Lesseps] as she dressed up as Diana Ross and she made her skin look darker than it really is. And people said that that was racist. And I don’t know, I felt like who doesn’t love Diana Ross? She wants to look like Diana Ross for one day. I don’t know how that got racist on Halloween. It’s not like she’s walking around like that in general. . . . I can’t keep up with the number of people we are offending by just being, like, normal people.1

Kelly’s statement in support of the use of blackface on Halloween relies on both the assumed innocence of a desire for verisimilitude (“Back when I was a kid [blackface] was okay as long as you were dressing up as like a character”) and the assumed innocence of a desire to celebrate others (“who doesn’t love Diana Ross? She wants to look like Diana Ross for one day”). And the logic and rhetoric of her position ends with an explicit appeal to white innocence (“I can’t keep up with the number of people we are offending by just being like normal people”). She is “normal people,” and her intentions should seem that way too, even if she were to apply blackface for Halloween (Figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1 In 2018, Megyn Kelly defended Luann de Lesseps “Diana Ross” costume by saying, “Who doesn’t love Diana Ross?” Twitter.

Kelly was immediately criticized by her colleagues and viewers. Don Lemon, a black journalist, took direct aim at Kelly’s claims to white innocence. In an interview on CNN, Lemon said to Chris Cuomo, “Megyn is 47 years old—she’s our age. There has never been a time in that 47 years that blackface has been acceptable.”2 Countering her claim that it was acceptable “back then” when there was no political correctness, Lemon reminds his audience that “back then” was the 1980s, not the 1880s. Kelly subsequently released a written apology and had an on-air discussion with people of color about cross-racial dressing. Nonetheless, NBC canceled her show the following day. At the time of writing this book, however, Megyn Kelly seems poised to make a comeback to television.

Example #2: Three months later on January 24, 2019, The Tallahassee Democrat, a local newspaper in Florida, released photos of Michael Ertel, Florida’s secretary of state. Ertel, who had served as the chief elections officer in Seminole County for fourteen years, had been appointed by Florida’s republican governor, Ron DeSantis, only a few weeks earlier in December 2018. The photo was from a 2005 Halloween party in which he appeared to be cross-dressed and blackfaced (Figure 2.2). Wearing a New Orleans Saints bandana, earrings, and large fake breasts under a blue T-shirt with the handwritten slogan “Katrina Victim,” Ertel appears in the 2005 image to be mocking the victims of Hurricane Katrina, the Category Five tropical cyclone that devastated New Orleans only two months earlier in August 2005. Hurricane Katrina caused numerous deaths, $125 billion in damages, and displaced one million residents.

FIGURE 2.2 In 2005, Michael Ertel, then the Seminole County supervisor of elections, donned blackface to portray a Hurricane Katrina victim at a Halloween party. Twitter.

Is it possible that Ertel felt he was honoring the victims through his Halloween costume? Was his costume an homage to the victims’ resiliency and style in the face of devastation? It’s conceivable, and we may never know. The Miami Herald reports: “In his resignation email, Ertel made no reference to the controversy that ended his brief term. His email signature quoted Abraham Lincoln: ‘These men ask for just the same thing, fairness, and fairness only. This, so far as in my power, they, and all others, shall have.’”3 While Ertel did not issue an explicit statement about his motives for creating and wearing his Halloween costume, his email signature quotation does rely on the logic of white innocence. His plea for fairness in the quotation from Abraham Lincoln—the American president who freed the enslaved in the Emancipation Proclamation—seems to indicate a belief in his own sense of morality and justice. Is it fair to force him to resign his office over a Halloween costume, the email signature quotation seems to be asking?

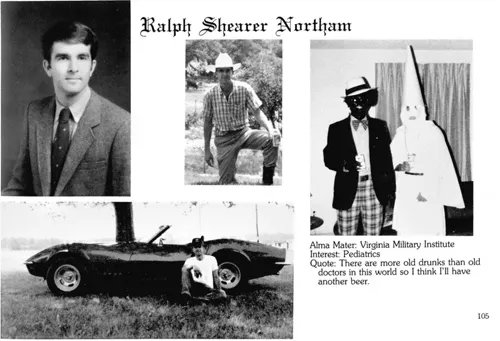

Example #3: Exactly eight days later, on February 1, 2019, the conservative website Big League Politics was the first media outlet to post images from Ralph Northam’s medical school yearbook (Figure 2.3). The democratic governor of Virginia, who had assumed his office in January 2018, graduated from Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, Virginia in 1984. His yearbook page contains four images: one a standard, posed school photo of him in a suit; one of him in a cowboy hat, holding a Budweiser beer can; one of him in a baseball cap sitting in front of a convertible; and one of two people both holding beer cans—one in blackface and one in a white Ku Klux Klan robe and hood. Governor Northam apologized immediately, saying “I am deeply sorry for the decision I made to appear as I did in this photo and for the hurt that decision caused then and now. This behavior is not in keeping with who I am today.”4

FIGURE 2.3 Ralph Northam’s 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook page includes an image of blackface.

Unlike Ertel, however, Northam resisted the calls for his resignation, and by the next day (February 2, 2019) his memory had been clarified about his appearance in blackface. In a press conference, Northam explained:

In the hours since I made my statement yesterday, I reflected with my family and classmates from the time and affirmed my conclusion that I am not the person in that photo. While I did not appear in this photo, I am not surprised by its appearance in the EVMS yearbook. In the place and time where I grew up, many actions that we rightfully recognize as abhorrent today were commonplace. My belief that I did not wear that costume or attend that party stems in part from my clear memory of other mistakes I made in the same period of my life. That same year, I did participate in a dance contest in San Antonio in which I darkened my face as part of a Michael Jackson costume. I look back now and regret that I did not understand the harmful legacy of an action like that. It is because my memory of that action is so vivid that I truly do not believe that I am in the picture of my yearbook. You remember these things.5

While Northam’s rhetoric, unlike Megyn Kelly’s or Michael Ertel’s, was apologetic, it still rested on the same belief in his white innocence (“I did not understand the harmful legacy of an action like that”). He even went on to explain that there was a critical difference between the yearbook photo, which was “offensive” and “racist,” and his made-up appearance as Michael Jackson at the dance contest, because: (a) it was a product of his time (“In the place and time where I grew up, many actions that we rightfully recognize as abhorrent today were commonplace”) and (b) it was an act of celebration performed in ignorance of its historical implications.

A reporter at the February 2, 2019, press conference asked, “Governor, at the San Antonio party you said you darkened your face. I just want to be perfectly clear, were you in blackface?” And Governor Northam elaborated, “I wasn’t. I mean, I’ll tell you exactly what I did, Alan. I dressed up as . . . Michael Jackson. I had the shoes. I had the glove, and I used just a little bit of shoe polish to put on my cheeks. And the reason I used a very little bit is because—I don’t know if anybody has ever tried that—but you cannot get shoe polish off. But it was a dance contest. I had always liked Michael Jackson. I actually won the contest because I had learned how to do the moonwalk.” When he was asked by a reporter if he could still moonwalk, the gov...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title

- Contents

- 1 Why Write This Book?

- 2 Megyn Kelly, Justin Trudeau, or (Fill in Another Public Figure’s Name)

- 3 What Is Blackface?

- 4 Why Does Blackface Exist? Because of Uppity Negros, of Course!

- 5 What Is the Legacy of Blackface? The Impact on White Actors

- 6 What Is the Legacy of Blackface? The Impact on Black Actors

- 7 Conclusion: I Can’t Breathe

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Blackface by Ayanna Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.