![]()

PART ONE:

WHAT YOU NEED IS LEARNABLE

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: Navigating the Pit of Success

Stephanie Shirley did not intend to become a pioneer in computing. She just liked math and was fascinated with computers in the 1950s. While attending night school, she worked days for the United Kingdom’s Post Office Research Station, assembling room-sized computers and teaching herself machine language programming. After graduating and working at a second firm, she decided it was time to start her own one-person programming company.

Stephanie gradually won programming contracts, including some that were beyond her level of experience, but the challenge never intimidated her, because she knew she had the talent and work ethic to solve any technical problem. She felt good about her success that first year until she received her tax returns and realized she was not getting ahead. She decided that she needed to build a scalable company, and with only £6 (approximately US$50 adjusted for inflation) of capital, she started the software company Freelance Programmers in 1962.

Stephanie could figure out how to program almost anything and worked hard to secure new projects, but she did not understand employee contracts, managing people, and cash-flow management. In her own words, “I didn’t even know the issues existed, let alone that I needed to master them.” Running a business was the first time that Stephanie felt in over her head. Despite her intelligence, optimism, and willingness to work hard, as her company grew, she was lost and floundering.

Stephanie often found herself being pulled away from doing what she loved—programming—to do the things she considered to be just “a headache,” namely, leading the business. She soon had so many problems with overseeing quality, attending key meetings, and managing work deadlines that after only two years, she was on the brink of having to shut down Freelance Programmers. She was having serious doubts about her ability to succeed as the leader of a company.

Stephanie Shirley had entered what we describe as a Pit of Success. That is, she stood at a turning point between what had made her good up until then and what would make her good in the future. In her case, she needed to choose between being an excellent programmer and an effective leader.

Stephanie chose to lead and focused on learning how to manage people and understand business logistics. She gained some knowledge by taking classes, and she sought guidance from experts in the field to learn what it meant to lead a business. The company slowly began to turn around, and in the next three years, her company started becoming profitable. Moreover, Stephanie was feeling more comfortable as a leader.

With her newly acquired abilities, Stephanie continued to win contracts, create standardization for quality control, and expand her business. By 1980, she had grown the company to six hundred employees, and by 1987, some 25 percent of the top five hundred companies in the United Kingdom were her clients. Stephanie’s willingness to navigate her pit of success, including her struggle to create standardization for her programming teams, resulted in the standards still used today by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to regulate software.

She has been honored many times for her pioneering work in information technology, including becoming a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering. In 2000, she was given the honor of Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (the equivalent of knighthood) for her contributions to computing.

Dame Stephanie Shirley retired at the age of sixty in 1993 and since then has donated £67 million (approximately US$87 million) of her personal wealth to philanthropic projects around the world. She continues to this day to give her time and money to worthy causes.

To achieve her success, Dame Stephanie Shirley had to take herself and her business through the pit of success.

Leaders Achieve with Their Doubts

In our interviews with Fortune 500 executives, new managers, mid-managers, doctors, parents, community leaders, and politicians, we have found that Stephanie’s struggles and doubts are shared by people in all walks of life and at all levels of leadership. And the reason is quite simple: the problems leaders face are routinely bigger than their experience. These challenges are the norm! Leaders are not in their jobs because they have all the answers to the problems. They are in their jobs to find answers.

Executives, parents, and other leaders routinely feel lost, confused, and overwhelmed as they try to find answers. Some leaders worry that they really are not up to the challenge. When they look around at others who seem so competent, they secretly wonder if they are alone in their struggles, and they wish they could keep doing what made them successful in the past.

Few leaders talk about these doubts because it does not seem “leader-like” to feel this way. Yet, no one is protected from these doubts. Your age, education, intelligence, gender, experience, position, or geography afford no safeguard from these uncertainties. When you face something bigger than your experience, you often feel doubt and confusion. In fact, uncertainty is one of the most common experiences shared by leaders across the planet. At some point, every leader faces a pit of success and wonders, “Am I good enough?”

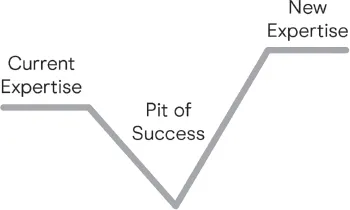

What Is a Pit of Success?

A pit of success is the space between your current expertise and your future expertise. A pit could be any challenge, demand, opportunity, or indignity that pushes you beyond your expertise. We call this space a pit because it is confusing and stressful. It creates a sense of loss, makes you feel inadequate, and rarely has a clear path forward. When you are in the pit, you frequently feel like a fake or an imposter.

You may have a pit imposed on your life through organizational changes, job loss, difficult people, health problems, divorce, financial difficulties, depression, abuse, or other people’s bad decisions. You did not seek these demands; nor did you deserve to have them come down on you. But you are stuck with them.

You may also have purposely chosen your pit of success, as Stephanie did. You might be seeking a promotion, taking on new responsibilities, pursuing a college class, starting a family, or learning a language. You believe these pits will make you better, so you seek them out, even though you know they will be demanding.

Either type of pit, imposed or chosen, can sometimes seem insurmountable. Imagining all the skills, interactions, decisions, and additional effort required to overcome it can be draining. Given the anticipated demands, you can easily begin to wonder how you will ever do it all.

These pits can make you feel that you should be better than you are. A pit can feel like a dark place with no exits—a place where you feel smaller than the task at hand. But being in a pit does not mean you are incapable; it only means you are unpracticed.

You transform your uncertainties into success when you redefine the pit. Rather than seeing it as something that minimizes you, you can redefine a pit as something that maximizes you—if you let it. By understanding how you progress from your current expertise through the pit and then to a new area of expertise, you can leverage a pit rather than avoiding or dreading it.

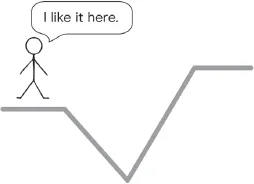

Enjoying Your Current Expertise

Your current expertise is the place where you perform certain tasks with ease. It is your mental home. You have worked hard and established a repertoire of skills, relationships, and knowledge through practice, trial and error, and study. When you are operating within an area of expertise and facing familiar challenges, it feels good. Your brain loves this space because it requires little effort. Familiar situations give you a sense of confidence.

Being in your expertise zone does not mean you are perfect— or even the best at the task. It simply means you have mastered a set of knowledge, skills, routines, and beliefs that allow you to repeat your current level of success at will. There is a lot of comfort in your expertise zone.

When Stephanie Shirley began her company, her current expertise included the following capabilities:

- Knowledge of computers and programming

- The ability to learn new programming languages

- Experience solving complex technical problems

- The ability to obtain contracts

- Consistency in delivering her own projects

Staying within her current expertise provided Shirley with fun and rewarding work. Her strengths in understanding the problem, anticipating the process, and programming quality software gave her great satisfaction. She would have preferred to continue relying on her expertise to solve her new challenges.

Your current expertise may be quite different from Stephanie’s, but the principle is the same. When you are in your current expertise, you feel confident. It is a place of strength. You know where things are, you know what needs to be done, and you know how to get things done. Here are a few typical ways you might experience your current expertise:

- Doing the work yourself

- Having a deep knowledge of a technology or process

- Predicting how long things will take to create

- Maintaining a network of stakeholders and colleagues

- Knowing a specific industry

When operating in your own area of expertise, you can predict success because you have been through this experience before. You know who to go to when you have a problem, and you can make timely decisions. This confidence allows you to move with ease. If the world never changed, your expertise would allow you to solve similar problems in the future.

But your current expertise is a bit of a paradox. On the one hand, your current skills, relationships, and mindset give you a foundation of strength for facing challenges. They give you power. These abilities protect you and give you competence to face the world.

On the other hand, the comfort of these strengths can also encourage you to avoid or even condemn unfamiliar and difficult demands. Because you invested heavily in your current expertise, the most natural thing to do is to rely on it, even when the situation no longer demands your strengths.

You do not cling to these strengths because you are lazy, stubborn, or stupid. You hold on to them because they have worked. They are the most natural response. But if left unchecked, your dependence on your current expertise will hold you back because it discourages you from discovering new and better approaches to problems. Managing this paradox helps you become more capable and resilient.

If Stephanie had insisted on sticking only with her current expertise, she could not have gained the skills she needed to lead a business. She had to overcome the paradox of her strengths and enter the pit.

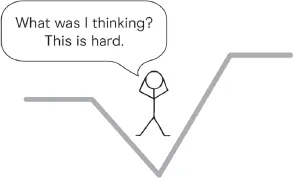

Entering the Pit of Success

The pit of success begins with that “Oh no” moment when you realize that your current skills, knowledge, and relationships will not solve the problem in front of you. You look at the challenge and wonder, “How can I ever do it?” or, better yet, “How can I simply avoid it?” Moving forward into the pit means leaving your emotional and intellectual home. You stand between knowing how to do the old thing and learning the new thing. In essence, you are between two places you want to be.

Pits come in many different shapes and sizes:

- You know how to get the work done yourself, but now you must create a strategy that others will execute.

- You have technical expertise in one domain, but now you must learn a new domain.

- You know how to manage a team, but now you are managing an organization.

- You know how to succeed in a growing market, but now you must make a profit in a declining market.

- You know how to care for a young child, but now you must care for aging parents.

The emotions of entering the pit are like those of new trapeze artists when they must swing fifty feet above the ground, let go of the solid trapeze bar, and hope that, when they let go and turn around, the other trapeze bar will be there. As they anticipate letting go, they wonder, “Do I really want to let go of this bar? What if my timing is just slightly off? Am I strong enough to make the catch?” The fact that a net waits below does not eliminate the uncertainty. The artists cannot know if they will make it until they let go of the bar. It is a moment of fear—and possibly exhilaration.

In Stephanie’s situation, not only did she have to let go of a bar that gave her great security and confidence, but she also had to make a huge stretch to catch a bar that was far away. She chose a new space requiring her to manage budgets, oversee the quality of others’ work, and maintain cash flow, when she would have preferred to just keep programming and ignore the administrative details of the business.

Stephanie occasionally felt like an imposter as she tried to juggle her new world of management. Everything about running the business was a difficult decision for her because she could not rely on her experience to guide her actions. She had to think through everything, and it all took so much time. There were many days when Stephanie wished she could just go back to doing all the programming herself.

Like Stephanie, you may wish you did not have to let go of your current expertise to face your pit of success. That is a common feeling leaders experience as they try to na...