![]()

It was easy to love God in all that was beautiful. The lesson of deeper knowledge, though, instructed me to embrace God in all things.

—Saint Francis of Assisi, The Writings of St. Francis of Assisi

Spirit, open my heart

to the joy and pain of living.

As you love may I love,

in receiving and in giving.

Spirit, open my heart.

—Ruth Duck, “Spirit, Open My Heart,” Glory to God: The Presbyterian Hymnal

December 2015

It was a cold Tuesday morning in December when Marty, highly agitated and visibly distressed, rushed into the church office. “Do you have a minute, Kara?” he asked.

He unzipped his heavy winter coat, pulled off his mittens, jerked a chair up to the desk, and shakily lowered himself into it. Reaching into his shirt pocket, he pulled out a folded piece of paper. With trembling hands, he gave it to me. “Could you look at this?”

I opened it. It was medical test results. For some time, Marty had had a cough and some tightness in his chest. Suspecting asthma, or something to do with the harsh Minnesota winter air perhaps, he had finally had some tests done the week before. Over the weekend, he’d gone online and viewed his results. Unable to reach his doctor, Marty had an appointment scheduled for Thursday—two days away. In the meantime, he had been carrying around this deeply creased printout of his test results next to his constricted chest. No longer able to bear the dread alone, he had driven over to the church building with them, and now he was handing them to me to read. “What do you think that means?” he asked, pleading.

I looked down at the paper in front of me. It was packed with words. But right in the center, the phrase rose up and nearly shouted off the page: tumors too numerous to count. My heart dropped into my stomach.

“I don’t know, Marty,” I answered. “It doesn’t sound good, does it?”

• • •

I am a pastor.

It’s a weird thing to be. It means people thrust test results under my nose and ask me what I make of them. It means they invite me to come over and anoint their belly the night before they go into the hospital to have a baby, because the last time they went into a maternity suite, their baby died, and they’re terrified this time around. It means I sit across from people and invite them to tell me stories about their dead parents so I can plan their funerals, and I sit across from parents and invite them to breathe when they tell me about finding drugs in their teenager’s laundry basket.

Being a pastor means I walk around all week mulling over a passage of the Bible—some story about Jesus, or a Psalm of David, or an admonition from the long-dead apostle Paul—until my own life and the world around me start to crack open and shed light into this Scripture, and vice versa. And then I sit on Friday and Saturday nights at my dining room table and pray and write until something appears and rearranges and aligns—and it feels mysterious and miraculous every time—to become a sermon I will stand up in front of people and preach.

Being a pastor means I’m self-employed for tax purposes, but I have dozens of bosses, with dozens of versions of my job description in their own minds, and lots of appreciation and gratitude, and lots of disappointment and frustration, and they’re all happening simultaneously at every moment.

Being a pastor means I work in a dying institution that can’t financially sustain itself, and yet year after year, we are still here. It means I work for a dying organization—a denomination—where all the well-thought-out structures, programs, and plans that flourished in decades past are crumbling and disappearing, and there is a general unease bordering on panic about what is going to become of this thing called “church.”

Being a pastor means that I work in a dying institution in a time when the customs and voice of the church are seen as increasingly archaic and unnecessary; there are plenty of therapists, death doulas, event planners, funeral directors, and groups of friends willing to do the duties once reserved for clergy. My teenaged kid came home from school the other day and announced that he got ordained online during study hall. (While his ordination was effective immediately, he will be required to wait, per state law, until he’s eighteen to officiate a wedding.) According to a recent Gallup poll, judges, day-care providers, police officers, pharmacists, medical doctors, grade school teachers, military officers, and nurses are all seen as more trustworthy than pastors.1 Esteem for organized religion is waning, and amid a smorgasbord of spiritual and religious options, the Christian church, with its flagrant rancor and division, is appearing less and less enticing, or necessary.

But I love the church.2 So much—really, all—of who I am is because of the church. It’s my root system and the nest where I was fed and from which I was launched into the world. It’s what I grappled with, and pushed away, and came back to, different, and saw with different eyes. I can’t not be in the church; I can’t not serve the church. Church is who I am.

Even so, experiences of church are not always life-giving, or even benign. Injury, hurt, rejection, and pain are wrapped up together with the beauty and hope that is church. Each human soul’s fear, hypocrisy, power mongering, and myopia are writ large here. Mix these with the search for meaning and longing for truth, and the results can be dangerous. There are lots of reasons people don’t stay, or leave and don’t return to church. But I stayed. I returned.

I lost almost everything to get here. Who I thought I was, who I thought God was, how I believed life worked, and what I believed church to be. My path to pastor has not been simple or clean or kind. I journeyed first through death, as, I’ve learned, all the paths that lead to real life do. Truth is here, even though churches only brush up against it from time to time, and that often by accident. And goodness is here that doesn’t come from—in fact, is quite apart from—all our striving to be good. The times I most feel my deep love for the church are when it’s transcendent, mysterious, and unknowable and when it’s messy, haphazard, and human. And my favorite moments of all are when it’s all of these at the same time.

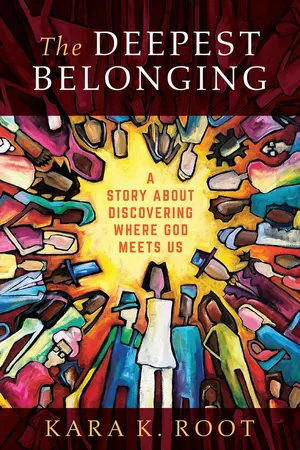

Church is a broken and messed-up collection of beautiful souls longing for the world to reflect the truth of God’s love. These people show up to be with each other, believing there is a reason to come, a reason to risk, a reason not to quit. Just think of it! Each person wakes up on a Sunday morning (if that’s when their congregation meets) and gets dressed, eats breakfast, gets into their car and drives, or takes a bus, or walks to this place and not another. Each person makes two dozen small choices in that direction, any one of which could shift the outcome. Each one chooses not to stay in bed, not to put on sweatpants and chip away at their to-do lists, not to turn the car in the other direction and do the grocery shopping instead, but to come to a gathering of people there to worship God. They come, in spite of a hundred other options, a hundred other ways to measure their day or parcel out their minutes, many of which may even feel more satisfying or productive. Even if they come just out of habit, underneath, somewhere, they believe church is a worthwhile use of their precious, limited time. Something in them believes they could receive something, or give something, or feel something, or learn something.

This is not a small thing. This thing we do called church, this churching. This trusting that God is real, trying to practice trusting that this is so, reminding each other that it is, is no small thing. Talking to God, even when it feels illogical; listening to stories from a book written centuries ago and cultures away as though it has something important to do with us, to us; repeating strange, ancient rituals with bread and wine; and engaging in institutional formalities with words like elders and ministry: these churching things we do, as church, help us know who we are. By coming together in this way, people are saying, This is what I choose to help define my life, to be known as, to shape me in some way. Even as so much around us changes, church is timeless, and deep, and it matters.

We are on a journey in this life. Sure, we are on a metaphorical journey, the kind people write poems about. But also, plain and simple, we come into this life, live it, and leave it; we are born, and we die. Every human life has a beginning, an end, and the span in between, however long or short that span may be. On this journey we are defined by two intertwined facts: we belong to God, and we belong to each other. Life includes lots of other ingredients, of course, but this is the inescapable essence of living a human life: we belong to God, and we belong to each other. We can act as though one or the other of them is not real. We can avoid or deny part of our belonging, behaving as though we are in this life alone and against others, or ignoring our belonging to God completely. But that doesn’t make either belonging not true. It just means we are disconnected or distracted, not sensing and living into our true human identity and connection at the moment.

We all have moments when we sense our deepest belonging; they often come without words. In the midst of a spectacular thunderstorm, we might feel the power and mystery of a universe far greater than ourselves. When we are lost in profound grief, someone’s presence with us momentarily anchors us and holds us fast. In an otherwise ordinary day, a tiny pause, a bright, subtle detail, a flash of humor or joy can suddenly make our breath catch and make us feel like we’re seeing beyond the surface into something true. Whether or not we acknowledge that God is there, whether or not we say out loud that we recognize our connection to all others, in experiences of inexplicable depth, surprising beauty, or great love, we are momentarily tasting our true belonging.

Church is those who acknowledge God is here and use words to say out loud our true connection to all others. Church is those who are human together—that is, we practice on purpose our real identity and our primary belonging: we remember whose we are, and we recognize who we are. Alongside other people, we lift our own souls to God, whose presence we acknowledge explicitly. Being church is remembering that we belong to God and we belong to each other. Being church does not mean coming to a building once a week, but by coming regularly and remembering together, we deepen our awareness of our belonging and practice trusting that it’s true every day of our journey from birth to death.

All the people who show up have their own reasons for coming. This is the reason I come, the reason I keep showing up: because I want to be awake to what’s real. I am letting church define and shape my life, because church makes me more human. It makes me more grateful. It keeps me attentive to the mystery. It opens me up to receive and live into the deepest belonging. And I’ve come to see and trust that when we humans come together and open our hearts—even a tiny bit for a tiny moment—to trust that there is something more, something transcendent, and that it even has something to do with us, God meets us. Every time. We already belong to God and to each other, so when we show up together with each other, God meets us.

Right around the time Marty wandered in and settled among us, we started saying just that aloud each week in worship. It feels too wonderful to grasp and too easy to forget, so we repeat it every time, “Wherever we are on our journey of faith, when we come together, God meets us.” In worship, we name this ungraspable thing, this divine and human dinner party of the soul. God is, of course, present at all times and everywhere. But especially here, especially now, when we answer God’s invitation and show up, God meets us. When we come to the set table prepared for us, ready to receive from our Divine host, God welcomes us and joins us here. I trust this completely, and I love church for this reason most of all.

So I’m a pastor. I have close to zero faith in institutions and lots of cynicism and impatience with organizations in general. I am not in this gig for doctrinal or even theological convictions, though certainly I have those. But this—that God is here, in every life, in every moment, tragedy, breakthrough, euphoric celebration, and ordinary second of boring monotony—this is what captures me. That every life is sacred to God, that every person’s melody is written into the limitless symphony, and that when we come together, we hear a bit of God’s eternal song playing out right now with us, every time—that is what has captured me. So it’s what I have given my life to; it’s my work as well as my belief. But it’s a strange job, hard to understand, difficult to explain in a culture of concrete objectives, rational calculations, and measurable, upwardly mobile ambitions. To stand with people together in the possibility of being met by transcendence, to hold open space for Divine encounter, there is no category for that on a W-2.

My son, Owen, had a best friend, I will call him Ben, all through his elementary school years. Ben’s parents were both doctors, and unlike anyone I had known well before, they had no religious affiliation at all and hadn’t had at any point in their lives. As far as I knew they could point to no faith they’d grown up with and left, no family spiritual roots, no church baggage they were carrying or religious chips on their shoulders. They were part of a growing population who seemingly never gave God a second thought or ventured to dip a toe into religion, saw no reason or need for such a thing. They lived with a strong ethical system of compassion and responsibility that guided them well.

This difference between us popped up every so often. Ben was sometimes curious that Owen believed in God. His parents were undoubtedly curious that Owen’s parents, who seemed like smart, ethical, rational people, both had careers in religion. Once, I saw his mom pause on my front porch and do a double take at the plaque we have hanging there: “Bidden or unbidden, God is present.” Probably they had never met people like us before either.

One New Year’s Eve we were together at a neighborhood party. Ben’s mom was telling me about spending time with a dear friend of hers whose mother was dying. It was painful for her friend to watch her mom deteriorate, and the experience was weighing heavily on her friend, she said. Then she looked right at me, and her tone grew frank. “I’ve been wanting to ask you about this. Her pastor has been there a lot. He sits with her in the hospital sometimes and has really been supporting my friend.” Then she looked at me with her curiosity wide open and asked, “Is that what you do?”

We are each on a journey in this world, making our way through life from our first breath to our last, walki...