- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

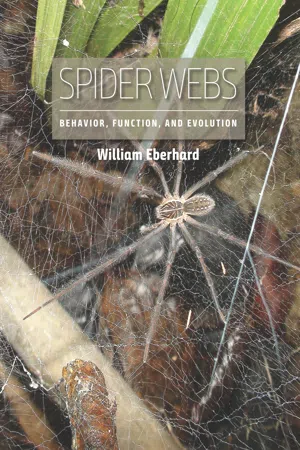

In this lavishly illustrated, first-ever book on how spider webs are built, function, and evolved, William Eberhard provides a comprehensive overview of spider functional morphology and behavior related to web building, and of the surprising physical agility and mental abilities of orb weavers. For instance, one spider spins more than three precisely spaced, morphologically complex spiral attachments per second for up to fifteen minutes at a time. Spiders even adjust the mechanical properties of their famously strong silken lines to different parts of their webs and different environments, and make dramatic modifications in orb designs to adapt to available spaces. This extensive adaptive flexibility, involving decisions influenced by up to sixteen different cues, is unexpected in such small, supposedly simple animals.

As Eberhard reveals, the extraordinary diversity of webs includes ingenious solutions to gain access to prey in esoteric habitats, from blazing hot and shifting sand dunes (to capture ants) to the surfaces of tropical lakes (to capture water striders). Some webs are nets that are cast onto prey, while others form baskets into which the spider flicks prey. Some aerial webs are tramways used by spiders searching for chemical cues from their prey below, while others feature landing sites for flying insects and spiders where the spider then stalks its prey. In some webs, long trip lines are delicately sustained just above the ground by tiny rigid silk poles.

Stemming from the author's more than five decades observing spider webs, this book will be the definitive reference for years to come.

As Eberhard reveals, the extraordinary diversity of webs includes ingenious solutions to gain access to prey in esoteric habitats, from blazing hot and shifting sand dunes (to capture ants) to the surfaces of tropical lakes (to capture water striders). Some webs are nets that are cast onto prey, while others form baskets into which the spider flicks prey. Some aerial webs are tramways used by spiders searching for chemical cues from their prey below, while others feature landing sites for flying insects and spiders where the spider then stalks its prey. In some webs, long trip lines are delicately sustained just above the ground by tiny rigid silk poles.

Stemming from the author's more than five decades observing spider webs, this book will be the definitive reference for years to come.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

1.1 Introduction

This book is about how spider webs are built, and how and why they have evolved their many different forms. It was conceived during a field trip in a spider biology course, when a student asked me why I had not written a book on spider webs. She noted that such a book would have been useful for the course but did not exist. She was right on both counts, and also that I was well-placed to produce it. I am an evolutionary biologist particularly interested in behavior. I have had the great fortune of living most of my working life in the tropics, and have spent just over 50 years watching a diverse array of spiders and thinking about their webs. Writing this book represents a chance both to contribute general summaries of data and ideas that are currently lacking, and to organize and develop new ideas that grew out of producing these summaries.

Inevitably, the book’s coverage is idiosyncratic. I propose more new ideas, give more new data, and discuss more extensively those topics related to behavior and evolution; some discussions in other areas, like the biochemistry and mechanics of silk, are more standard and less original. I focus on behavior and evolution partly because spider webs have the potential to make especially important contributions to resolving central questions in behavior and evolution, just as they did in the past in understanding the characteristic and limits of innate behavior (Fabre 1912, Hingston 1929). An orb web can be easily photographed with perfect precision, and it constitutes an accurate record of a series of behavioral decisions made by a free-ranging animal under natural conditions. And because a web-building spider’s sensory world is so centered on silk lines, the orb is also a precise record of some of the most important stimuli that the spider used to guide those decisions; in addition, these stimuli can be experimentally altered by making simple modifications of webs. These advantages offer unusual chances to study some basic questions in animal behavior with especially fine detail and precision.

I hope that this book may help future observers to see how web-building spiders can be exploited to investigate exciting new questions in animal behavior. It is a fragment of a larger project that originally included several additional topics: the role of behavioral canalization and “errors” in the evolution of behavior; the importance of scaling problems in the absolute and relative brain sizes of tiny animals and the limitations in behavioral capabilities that they may impose; the organization and evolution of independent behavior units in the nervous system; the implications of chemical manipulations performed by parasitoid wasps on their spider hosts and of additional experimental manipulations of webs for how behavioral subunits are organized and controlled in the spider; and the possibility that small invertebrates understand, at least to some limited degree, the physical consequences of their actions and the role that such understanding may play in the evolution of new behavior patterns. Other fragments of this larger project are archived online at the University of Chicago Press at press.uchicago.edu/sites/eberhard/; these portions are designated in the text with a capital O followed by the book chapter to which they refer (e.g., section O6.1; table O3.3; fig. O9.1). My hope is that this book will help to project the study of spider webs back onto the forefront of studies of animal behavior.

1.2 A foreign world: life tied to silk lines

Spiders are ecologically extremely important: for instance, a recent estimate suggests that they capture 400–800 million metric tons of prey each year, or about 1% of global terrestrial net primary production (Nyffeler and Birkhofer 2017). Web spiders live in a world that is ruled by their silk lines. This world is so different from ours, with respect both to their sensory impressions and to the basic facts of what is and what is not feasible for them to do, and they have such exquisite adaptations to this world, that it is useful to briefly describe these differences here, anticipating more detailed descriptions in later chapters (references documenting these statements will be given later). My aim is to help give the reader the kinds of intuition that are needed to understand their behavior.

Orb weavers are functionally blind with respect to their web lines. Their eyes are neither designed nor positioned correctly to resolve fine objects like their lines, and in any case many spiders build their webs at night. Watching an orb weaver waving her legs as she moves is thus like watching a blind man use his cane, with two differences: the spider is usually limited to moving along only the lines she has laid (and thus has to use her “canes” to search for each new foothold); and the lines are in three rather than two dimensions. Slow motion recordings reveal a further level of elegance. Spiders economize on searching as they walk through a web; one leg often carefully passes the line that it has grasped to the next leg back on the same side before moving on to search for the next line. Each more posterior leg needs to make only a quick, small searching movement in the vicinity of the point that is being grasped by the leg just ahead of it.

This dominance of the sense of touch gives observations of orb weaver behavior a dimension that is largely missing in many other animals, because the spider’s intentions can be intuited from the movements of her legs. One can deduce a blind man’s intentions by watching the movements of his cane; when he taps toward the left just after he hears a sudden growling sound from that direction, he is probably wondering about the origin of that sound. And it is also clear what he has found out; if his cane has not yet touched the dog that growled, he probably does not yet know its precise location. The searching movements that a spider’s legs make to find lines, especially at moments during orb web construction, when one can predict the next operations that she will perform, make it possible to confidently deduce both her intentions and the information that she has perceived. For instance, when the orb weaver Leucauge mariana is moving back toward the hub after attaching the first radial line to a primary frame while she is building a secondary frame (when she is at approximately the site of the head of the inward arrow from point p in fig. 6.5j), she consistently begins to tap laterally with her anterior legs on the side toward the adjacent radius (o in fig. 6.5j) that she is about to use as an exit to reach the second primary frame. The movements and their timing leave no doubt about what she is attempting to do: she is searching for the adjacent radius. In some cases it is possible to deduce, even in a finished web, what the spider may or may not have sensed at particular moments during the web’s construction by taking into account leg lengths and the distances between lines. This access to both the intentions and the information that an animal has (or lacks) offers special advantages in studies of animal behavior.

An orb weaver is also largely chained to its own lines. In one sense, the spider lives a life similar to that of a blind person who is constrained to move only along preexisting train tracks. And just like a blind man walks around and taps objects in a room to sense its size and the presence or absence of furniture in it, the spider searching for a site in which to build a web must explore it physically, rather than surveying it visually. Much of this exploration must occur by following lines that were already laid previously; the spider cannot simply set out in any arbitrary direction. While spiders sometimes lay new lines by walking along a branch or a leaf and attaching the dragline line, at other times the only way for the spider to lay a new line from one distant point to another is by floating a line on a breeze and waiting until it snags somewhere. The spider has no control over the strength or direction of the wind, nor how or where the line snags. If the line fails to snag firmly on a useful support object, the spider’s only recourse is discard it and try again. To evaluate a possible website (is it too large? too small? does it have a projecting branch that would interfere with a web?), the spider probably remembers the distances and directions she has moved while exploring it (sections 6.3.2, 7.8).

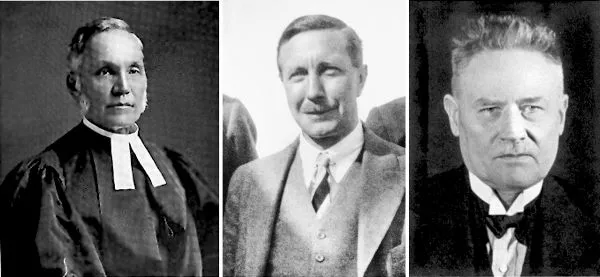

Fig. 1.1. Three outstanding observers of spider webs and building behavior from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (left to right): Rev. Henry C. McCook, Major R. W. G. Hingston, and Emil Nielsen (the last two courtesy of, respectively, Royal Geographic Society, and Nicolas Scharff).

And then there is the web itself. Orbs are famously strong, and able to resist both the general loads imposed by wind and the local stresses from high-energy prey impacts. But they are also foreign to some human intuitions. The lines are extremely light, and because air is relatively viscous at the scale of a small animal like a spider, transverse vibrations that would dominate a web at a human scale are strongly damped in spider webs. A more appropriate image is an orb of flexible lines strung under water. Not unexpectedly, spiders rely mainly on longitudinal rather than transverse vibrations of their lines to sense prey and other spiders. And while an orb is strong, it is also delicate in unexpected ways. A few drops of rain, a fog, or even dew can be enough to ruin it: the sticky spiral lines adhere to each other, the radii, and the frame lines, and the sticky material on the lines of most species washes off in water. Wind can cause individual sticky lines to flutter and become damaged when they swing into contact with each other. Some patterns in sticky spiral spacing in orbs may represent adaptations to reduce this type of damage (section 3.2.11).

In sum, web-building spiders live a life that is limited by their own senses, and tightly bound to the silken lines in their webs. To understand these spiders, it is necessary to understand their webs, and vice versa.

1.3 A brief history of spider web studies

Spider webs are, of course, common and easily observed. The history of scientific inquiry regarding webs and spider building behavior begins, as with that of many other fields in biology, with descriptions by field naturalists. Important early works, now difficult to obtain and which I have not read, included Quatremére-Disjonval 1792, 1795, Reimarus and Reimarus 1798, Blackwall 1835, Dahl 1885, and Wagner 1894. The American clergyman H. C. McCook (Fig. 1.1) (in addition to providing distinguished service in the American Civil War and writing popular children’s books on insects, religion, and leaf cutter ants) described many details of natural history and behavior in unprecedented detail (McCook 1889). The nineteenth-century giant of spider taxonomy, Eugene Simon, also contributed scattered but precise observations of webs (Simon 1892–1903). Also important, with acute observations and the first collections of good photographs of webs, were the books of Emerton (1902), Comstock (originally published in 1912, revised in 1967), and Fabre (1912).

Somewhat later, perhaps the two best naturalist observers of spider orb webs and of building behavior were the Irish medical doctor and explorer Maj. R. W. G. Hingston (Hingston 1920, 1929, 1932) and the Danish school teacher Emil Nielsen (Nielsen 1932) (Fig. 1.1). Hingston parlayed military assignments in India, Pakistan, and Iraq, and subsequent expeditions to British Guyana and other sites, into opportunities to observe tropical spiders (and other animals) and describe their behavior. His careful observations of the details of web construction, his incisive simple experiments, and his thoughtful analyses are particularly striking in light of his energetic physical undertakings, which included participation in an expedition to climb Mount Everest and scaling tropical trees to collect specimens on the trunks and in the canopy. The other giant contrasted in many ways. Emil Nielsen was a Danish secondary school teacher who did not travel to exotic places to study spiders, but instead made thorough, careful comparative studies of web-building spiders in Denmark. He published an especially thorough book-length study in Danish and, mercifully for English-speakers, combined it with a condensed companion volume in English (Nielsen 1932). Nielsen’s work on the parasitoid wasps that induce changes in the web-building behavior of their host spiders was also exceptionally thorough and insightful. Both Hingston and Fabre discussed general questions regarding “instinctual” behavior and the limits of the mental and behavioral capabilities of invertebrates, comparing them with other animals and humans.

Other especially important general studies in the field of webs and their diversity were those by Herman Wiehle (1927, 1928, 1929, 1931) in northern Europe and the Mediterranean, Hans Peters (1931, 1936, 1937, 1939, 1953, 1954, 1955) in Germany, the Mediterranean, and tropical America, and B. J. and M. Marples in Europe and Oceania (Marples and Marples 1937; Marples 1955). Additional laboratory studies of orb web construction behavior during this and the following generation mostly centered on two European araneids, Araneus diadematus and Zygiella x-notata (e.g., Peters 1931, 1936, 1937, 1939; Tilquin 1942; König 1951; Mayer 1952; Jacobi-Kleemann 1953; Witt 1963; Le Guelte 1966, 1968; Witt et al. 1968), and the American uloborid Uloborus diversus (Eberhard 1971a, 1972a). Studies of the webs of isolated species continued, and began to include more tropical species (e.g., Robinson and Robinson 1971, 1972, 1973...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. The “hardware” of web-building spiders: morphology, silk, and behavior

- Chapter 3. Functions of orb web designs

- Chapter 4. Putting pieces together: tradeoffs and remaining puzzles

- Chapter 5. The building behavior of non-orb weavers

- Chapter 6. The building behavior of orb-weavers

- Chapter 7. Cues directing web construction behavior

- Chapter 8. Web ecology and website selection

- Chapter 9. Evolutionary patterns: an ancient success that produced high diversity and rampant convergence

- Chapter 10. Ontogeny, modularity, and the evolution of web building

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Spider Webs by William Eberhard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences biologiques & Évolution. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.